Cultural Diversity and Care

Joan C. Engebretson

Nurse Healer OBJECTIVES

|

Theoretical

Compare common value orientations associated with culture.

Describe the influence of technology on cultural development and communication systems.

Analyze components of cultural diversity.

Describe the components and principles of cultural competence.

Discuss cultural influences on beliefs and explanatory systems related to health and illness.

Clinical

Discuss the role of culture in interactions with clients.

Use components of transcultural assessment in caring for clients.

Identify appropriate patterns, challenges, and needs of clients in the cultural domain.

Explore interventions that reflect cultural competence.

Discuss ways in which nursing interventions may be evaluated in relation to cultural competence.

Personal

Clarify your own values, beliefs, and ideas related to your cultural heritage.

Identify barriers in your own life to acceptance of cultural diversity.

Explore activities that will increase your awareness and acceptance of cultural differences.

DEFINITIONS

Acculturation: The process of the adaptation or accommodation of an individual immigrant or immigrant group to a new culture.

Culturally competent health care: Health care delivered with knowledge of and sensitivity to cultural factors that influence the health and illness behaviors of an individual client, family, or community.

Culture: The values, beliefs, customs, social structures, and patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that provide meaning and significance to human behavior.

Ethnicity: Designation of a population subgroup sharing a common social and cultural heritage.

Ethnocentrism: A worldview that is based to a great extent on the socialization of individuals within their own culture, to the extent that such individuals believe that all others see the world as they do.

Race: A social classification that denotes a biological or genetically transmitted set of distinguishable physical characteristics.

Stereotyping: Consigning cultural attributes to a group of people based on assumptions, opinions, or attitudes.

Xenophobia: An inherent fear or hatred of cultural differences.

▪ THEORY AND RESEARCH

Culture is the combination of ideas, customs, skills, arts, and other capabilities of a people or group, although as a whole, it is more complex than any one of these elements. Culture is learned from birth through language acquisition and socialization and is the process by which an individual adapts to the group’s organized way of life. This process also provides for the transmission of culture from one generation to another. Members of the cultural group share cultural values, beliefs, and patterns of behavior that create and reflect a group identity. This has a powerful influence on behavior, usually on a subconscious level. Culture is largely tacit, meaning it is not generally expressed or discussed at a conscious level. Most culturally derived actions are based on implicit cues rather than written or spoken sets of rules.

Although many of the underlying beliefs and value systems of a culture are stable, all cultures are inherently dynamic and changing; therefore, it is difficult to generalize from one person, situation, or time to another. Cultural practices are continually adapting to the environment, historical context, technology, and availability of resources. As a result, the context in which people live influences, and is influenced by, cultural practices.

Anthropology, the study of cultures, and nursing are both based on a holistic perspective that incorporates the issues of context. Culture has a significant impact on health and illness behaviors, as well as patterns of response to illness or medical care. It directly influences health behaviors such as diet and exercise. Cultural beliefs and practices also affect the types of health problems that are attended to and the actions taken to deal with them. Activities taken to promote, maintain, or restore health are all performed in a cultural context. Therefore, an understanding of the client’s perceptions and the context in which he or she lives is necessary for optimal client care.

Culture also determines much of the relationship and type of communication between a client and a healthcare provider. Given that the United States is a culturally diverse nation, nurses and other healthcare providers encounter individuals and groups whose habits of health maintenance, reactions to illness or disease, and use of healthcare services may differ from their own. An awareness of and accommodation to the cultural aspects of health and illness behaviors enables one to promote health by skillfully blending professional knowledge with knowledge of the individual’s or group’s beliefs. Culturally competent care is the delivery of health care with skill, knowledge, and sensitivity to cultural factors. With the increase of cultural pluralism in North America, it is essential that nurses develop cultural competency to deliver holistic care.

Cultural Competency

With increasing diversity in the population, and the recognition that health disparities exist across ethnic groups, healthcare regulatory agencies recommend that cultural competency become a goal in the provision of health care. The Office of Minority Health developed standards and recommendations that apply to the institutional level as well as to the individual provider.1 Institutions are mandated to provide adequate translation, and individual providers are encouraged to develop more culturally appropriate care.

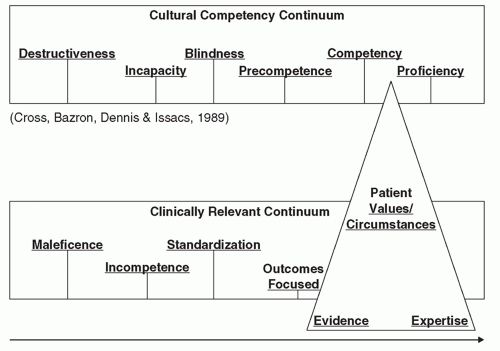

The idea of developing cultural competence has been increasingly discussed in the literature. The National Center for Cultural Competency at Georgetown University developed an often cited conceptual framework created by Cross, Barzon, Dennis, and Issacs that describes a continuum from cultural destructiveness to cultural competency.2 This continuum positions cultural destructiveness at the lowest level, with four intermediary steps to cultural proficiency at the top. This continuum can be viewed as corresponding to well-established values in medicine. Figure 30-1 illustrates this continuum along with parallel values in biomedicine with a recent value of evidence-based practice superimposed on the model.3

Cultural destructiveness, the lowest level of the continuum, corresponds to maleficence in medicine and this is countered through laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), which mandates that healthcare providers do not discriminate

according to race, ethnicity, or creed. The ethic of nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” also addresses this basic level. The second level of the continuum, cultural incapacity, corresponding to incompetence, refers to nonintentional practices that may be harmful to clients through ignorance, insensitive attitudes, or improper allocation of resources. Cultural blindness, the third level that corresponds to standardization, is exemplified by treating all patients alike without accommodating or recognizing cultural differences. Precompetence, corresponding to outcomes-focused care, is the next step toward cultural competence and proficiency. Providing translators, developing health education aimed at specific cultural groups, and creating programs that address diverse groups’ access to care are good examples of cultural precompetence, which is level 4. Cultural competence, level 5, is best described as an ongoing learning process for the provider, who can integrate cultural knowledge into individualized client-centered care. This eventually leads to the highest level of the continuum, cultural proficiency. These two levels correspond to the movement to patient-centered care, or what holistic nurses would identify as individually focused holistic care.

according to race, ethnicity, or creed. The ethic of nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” also addresses this basic level. The second level of the continuum, cultural incapacity, corresponding to incompetence, refers to nonintentional practices that may be harmful to clients through ignorance, insensitive attitudes, or improper allocation of resources. Cultural blindness, the third level that corresponds to standardization, is exemplified by treating all patients alike without accommodating or recognizing cultural differences. Precompetence, corresponding to outcomes-focused care, is the next step toward cultural competence and proficiency. Providing translators, developing health education aimed at specific cultural groups, and creating programs that address diverse groups’ access to care are good examples of cultural precompetence, which is level 4. Cultural competence, level 5, is best described as an ongoing learning process for the provider, who can integrate cultural knowledge into individualized client-centered care. This eventually leads to the highest level of the continuum, cultural proficiency. These two levels correspond to the movement to patient-centered care, or what holistic nurses would identify as individually focused holistic care.

Evidence-based practice has been an important issue in healthcare delivery. It grew out of the outcomes-focused value, as an effort to incorporate the best research evidence in healthcare delivery. In the focus on applying these findings, many revert back to standardized care or cultural blindness. According to some of the leaders in the evidence-based practice field, practicing in a culturally competent manner incorporates three aspects of evidence-based practice (EPB): best evidence from valid and clinically relevant research, provider’s clinical expertise, and the client’s values, unique preferences, and situation.4 The emphasis on the client’s values, preferences, and situation moves EBP into cultural competence and proficiency. Much of the literature in cultural competency also tends to focus only on the evidence or the studies or the literature that describes particular ethnic groups. It is important for holistic nurses to recognize that applying that information to clients of a specific ethnic group is only at the precompetence level at best. However, at the individual patient-provider encounter, it must be individually based and patient-centered.

Culturally competent health care must be provided within the context of a client’s cultural

background, beliefs, and values related to health and illness to attain optimal client outcomes. To enhance one’s understanding of cultural issues, it is therefore important for nurses to continue their understanding of cultural diversity. In addition to the Transcultural Nursing Society, there is a corpus of literature in nursing about cultural competence.5,6,7,8,9,10

background, beliefs, and values related to health and illness to attain optimal client outcomes. To enhance one’s understanding of cultural issues, it is therefore important for nurses to continue their understanding of cultural diversity. In addition to the Transcultural Nursing Society, there is a corpus of literature in nursing about cultural competence.5,6,7,8,9,10

A plethora of sensitivity training and educational programs has been implemented, and curricula have been developed in nursing and other healthcare professions. Lipson and Desantis recently reviewed a number of approaches in nursing education and concluded that there is a lack of consensus on what should be taught and how it should be integrated into the curricula.11 A recent systematic review of healthcare provider education was also conducted, concluding that cultural competence training shows promise for improving knowledge, attitudes, and skills of the healthcare professionals. However, there was little evidence in client outcomes.12 Most educational approaches have addressed knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Knowledge has often focused on facts and characteristics about specific cultures. This “cookbook” approach has been criticized as leading to stereotyping. The approach of cultural sensitivity training attempts to address attitudes. What seems to be more valuable is for providers to learn a set of skills that enables them to provide high-quality client care to everyone.

In a literature review of cultural competence and the clinical encounter, Betancourt concludes that healthcare providers develop the skills for a client-centered approach that does the following: (1) assesses core cross-cultural issues, (2) explores the meaning of the illness to the patient, (3) determines the social context in which the patient lives, and (4) engages in a negotiation process with the patient.13 Cultural competence represents an important element of clinical care and skills that are central to professionalism across disciplines. The relationship between cultural competency and improvement in health outcomes is not yet firmly established and more research is warranted.14 Although there is much emphasis now on developing cultural competency, there is also a developing awareness that competency is always a growth process, which means that it requires more than an accumulation of facts about different cultures.15 The clinical encounter, in which cultural competency is most demanding, requires individual- or family-centered care.16

Cultural Diversity and Health Disparities

Despite the fact that human beings are 99.9% identical at the DNA level, there are differences in prevalence of illness between groups. This may be explained by genetic differences; dietary, cultural, environmental, and socioeconomic factors; or combinations thereof.17 Health disparities in the United States exist for multiple health outcomes. For example, in the United States, infant mortality is inversely related to the mother’s educational level. It is also highest for infants of non-Hispanic black mothers and is lowest for those of Chinese mothers.18 According to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, some of the key social determinants of health include education and income, inadequate and unhealthy housing, unhealthy air quality, and health insurance coverage.19 Socioeconomic status underlies three major determinants of health: access to health care, environmental exposure to health-related agents, and health behaviors.20

Race and Ethnicity

Ethnicity refers to values, perceptions, feelings, assumptions, and physical characteristics associated with ethnic group affiliation. Often, ethnicity refers to nationality—a group sharing a common social and cultural heritage. In contrast, race typically refers to a biological, genetically transmitted set of distinguishable physical characteristics. In some literature, however, race has often been misused to describe differences in people that have no basis in biology or science. Demographic data are commonly gathered with no differentiation of ethnicity or definitions of race. Both skin color and country of origin have been used to classify race. For example, many natives of India (considered racially Caucasian) have darker skin than do many natives of Africa.

Race and culture have significant relationships to illness states because biological differences can make certain groups of people vulnerable to specific diseases. For example, genetic predisposition

for sickle cell disease affects people of African and Mediterranean descent; predisposition for Tay-Sachs disease affects Ashkenazi Jews. Also, certain diseases that may be attributable to a combination of genetic predisposition and lifestyle, including nutritional patterns, are more prevalent in some groups. One example is the disproportionately high prevalence of diabetes in Native Americans and Hispanics. Some diseases are connected to lifestyle risks, such as substance abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, which are related to particular social behaviors. An emerging body of information on the differences in response to pharmaceuticals by ethnic and racial groups has led to a new field of pharmacogenomics.21 Cultural subgroups can be identified by virtue of shared experiences or circumstances that may influence values, beliefs, and behaviors. Ethnicity is the most common cultural demarcation, but intraethnic variations may be more pronounced than interethnic variations, especially in a culturally pluralistic society. Other variables that have been proposed as influencing cultural groupings are religion, socioeconomic status, geographic region, age, common beliefs, and professional orientation, such as nursing and medicine.

for sickle cell disease affects people of African and Mediterranean descent; predisposition for Tay-Sachs disease affects Ashkenazi Jews. Also, certain diseases that may be attributable to a combination of genetic predisposition and lifestyle, including nutritional patterns, are more prevalent in some groups. One example is the disproportionately high prevalence of diabetes in Native Americans and Hispanics. Some diseases are connected to lifestyle risks, such as substance abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, which are related to particular social behaviors. An emerging body of information on the differences in response to pharmaceuticals by ethnic and racial groups has led to a new field of pharmacogenomics.21 Cultural subgroups can be identified by virtue of shared experiences or circumstances that may influence values, beliefs, and behaviors. Ethnicity is the most common cultural demarcation, but intraethnic variations may be more pronounced than interethnic variations, especially in a culturally pluralistic society. Other variables that have been proposed as influencing cultural groupings are religion, socioeconomic status, geographic region, age, common beliefs, and professional orientation, such as nursing and medicine.

Factors Related to Culture

Along with ethnicity, religion is an important factor in determining the values and beliefs of a culture.22 Religion, an organized system of beliefs, is differentiated from spirituality, which is born out of each individual’s personal experience in finding meaning and significance in life. Religious faith and the institutions derived from that faith have a powerful influence over human behavior. All religions have experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, and consequential dimensions. Religious views have historically served as a unifying force for groups of people with a set of core values and beliefs.

Socioeconomic status refers to an individual’s social status, occupation, education, economic status, or a combination of these. Socioeconomic explanations are often discounted when determining the relationships between ethnicity or race and health status or health. It is necessary to distinguish between cultural identification and the common experience of being poor in our society. By illustration, the experience of being poor in our society is different from that of being Hispanic, and also must be further distinguished from being both poor and Hispanic. The impact of socioeconomic status on both morbidity and mortality measures of specific groups is highly significant and is related to health disparities; lower socioeconomic status groups have higher morbidity and mortality rates for various diseases.23

The local or regional manifestations of the larger culture bring up such distinctions as rural, urban, southern, or midwestern. For example, African Americans living in the southern region of the United States may have beliefs and behaviors different from those in the northern region, based somewhat on their heritage of slavery and exposure to the civil rights movement.

Age of the individuals within a cultural group has a profound influence on their beliefs and behaviors as well. Value systems are tied to historically shared events that occur in childhood; therefore, each generation develops a unique value system. For example, there is much in the popular literature about the differences between the baby boomers (people born in the late 1940s and 1950s), generation X (those born in the 1960s and 1970s), and generation Y (folks born in the late 1970s and 1980s).

Common beliefs or ideologies may unite a cultural group or subculture, as well as differentiate that group from the larger culture. These value systems may be related to religion (e.g., the Amish), lifestyle (e.g., communal groups), sexual orientation (e.g., gay and lesbian groups), or political ideologies (e.g., feminist separatist groups). Social or professional orientations often constitute a type of cultural grouping. Medical anthropologists have described the biomedical system as a cultural system.24 The biomedical culture of many hospitals constitutes an unfamiliar culture for many laypeople. Healthcare professionals use unique and esoteric language, as well as rituals, roles, expectations, patterns of behavior, and symbolic communication that are often alien to the layperson.

Common Myths and Errors

Errors of stereotyping are common among those who define the world by strict categories

of ethnicity or race. It is also problematic to presume that all members of another culture conform to a common pattern without regard to individual characteristics or the variety found within one cultural grouping. For example, some people assume that all African Americans eat soul food or that all Hispanics are Catholic. Failure to recognize that values from a particular cultural group can vary across time and location leads to stereotyping cultures with values that no longer guide the group’s or the individual’s thinking or behavior. Stereotyping is less obvious in some cases, such as a nurse manager assigning all Hispanic clients to the Mexican American nurse. Such action does not take into account the differences within the Hispanic group, presumes that all Hispanics are alike, and disregards the individual.

of ethnicity or race. It is also problematic to presume that all members of another culture conform to a common pattern without regard to individual characteristics or the variety found within one cultural grouping. For example, some people assume that all African Americans eat soul food or that all Hispanics are Catholic. Failure to recognize that values from a particular cultural group can vary across time and location leads to stereotyping cultures with values that no longer guide the group’s or the individual’s thinking or behavior. Stereotyping is less obvious in some cases, such as a nurse manager assigning all Hispanic clients to the Mexican American nurse. Such action does not take into account the differences within the Hispanic group, presumes that all Hispanics are alike, and disregards the individual.

The heterogeneity of ethnic groups is often underestimated, but as mentioned earlier, the variations within ethnic groups may be as great or greater than those between ethnic groups. For example, the Hispanic culture includes persons of Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish, and South and Central American origins. These people are from many different socioeconomic backgrounds and represent the Caucasian, Mongoloid, and Negroid racial groups. Sometimes Asians from different countries and backgrounds are grouped together and treated as generic Asians, an attitude that totally ignores the historical differences among Asians. Kipnis relates a clinical incident that occurred in Hawaii in which a Korean client with a serious medical condition refused a treatment that promised a better than 50% recovery with minimum risks.25 Clinical staff were puzzled by his refusal of treatment coupled with his request for life support if he experienced cardiopulmonary arrest. On further investigation, he mentioned that all his physicians were Japanese. In the early 1900s, Japan had ruthlessly tyrannized Korea, much as the Nazis in Germany tyrannized Poland prior to and during World War II. Thus, the Korean gentleman very much wanted to live, but his cultural history caused him to refuse treatment directed by the Japanese physicians.

Ethnocentrism is the tendency, usually unconscious, for individuals to take for granted their own values as the only objective reality and to look at everyone else through the lens of their own cultural norms and customs. Ethnocentric views often result from a lack of knowledge of other cultures and the presumption that one’s own behavior is not influenced by culture. Many people of the dominant culture falsely assume that they have no cultural practices and beliefs. This restrictive view of the world perceives people and cultures with different beliefs and behaviors as culturally inferior. An extreme and more conscious form of ethnocentrism is xenophobia, an inherent fear of cultural differences, which often leads people to bolster their security in their own values by demeaning the beliefs and traditions of others. This attitude often takes the form of prejudice or racism.

Cultural imposition is the perception that successful cultural adaptation involves a change to the cultural views of the dominant group, regardless of an individual’s cultural heritage. This posits an inherent view that the dominant culture is superior, and its values are imposed on others.

Often disguised as equal treatment for everyone, cultural blindness ignores cultural differences as if they did not exist. This view overlooks real diversity and the importance of other perspectives. The concept of the “melting pot” assumes that, in the process of acculturation and assimilation, everyone takes on significant aspects of the dominant culture such that the original culture is largely lost. This assimilation or melting pot view is challenged by concepts of heritage consistency, which is the degree to which one maintains practices and beliefs that reflect one’s own heritage.

Development of Cultural Patterns and Behaviors

Anthropologists have studied practices among cultures in relation to the universal experience of being human. Their major focus has been on the variation of ways that humans organize and structure their social world. Some of the factors that contribute to the development of cultural patterns and behavior are geography and migration, gender-specific roles, value orientations and cultural beliefs, and technological development.

Geography and Migration

Social groups evolve through interaction with the climate, as well as in conjunction with the

availability of food and resources. The persistence of dietary patterns reflects the types of food available in a particular region. For example, fish constitutes a large portion of the traditional diet of people from Norway and the Philippines, whereas dairy products and meats are dominant in the food patterns of Finland and Germany.

availability of food and resources. The persistence of dietary patterns reflects the types of food available in a particular region. For example, fish constitutes a large portion of the traditional diet of people from Norway and the Philippines, whereas dairy products and meats are dominant in the food patterns of Finland and Germany.

Social organization falls in line with these geographic patterns. For example, the social structure of a fishing village differs from that of a nomadic group that hunts for food, and from that of a settled agrarian culture. Urbanization and industrialization are also important for the way society organizes and social roles develop. Social roles become patterned and often institutionalized into hierarchical structures that reflect social, economic, and political power. These social structures and roles greatly alter people’s daily lives and the economics of providing for families.

Climate, environmental conditions, and political and economic factors are very important in migration patterns. Climate change, famine, political upheaval, and overpopulation have all been responsible for migration. For example, a large wave of Irish immigrants came to the United States in the late 1840s following a potato famine that was causing starvation, disease, and death in Ireland. Many immigrants came to the United States to flee political unrest in El Salvador in the 1980s. Many Vietnamese and Southeast Asians sought political refuge and opportunities in the United States following the Vietnam War. A large number of nurses seeking professional and economic opportunities moved to the mainland United States from the Philippines in the 1980s. Even in the 1990s and the early 21st century, a large number of immigrants have steadily come to the United States seeking economic opportunities.

Cultural patterns change through the sharing of ideas, beliefs, and practices that follow trade or migration. Immigrants bring cultural patterns, values, and beliefs with them. Along with their adaptation to the new host culture, they expose the host culture to a different set of cultural beliefs and practices. Both cultures assimilate aspects of the other.

The historical context of immigration is important and varies among groups. Many African Americans arrived involuntarily and endured a lengthy history of slavery. Hispanics may be immigrants seeking economic opportunity, refugees from political upheavals, or descendants of people living in the Southwest before it became a part of the United States. The fact that many Asian immigrants find it necessary to take a job with lower status than they had in their country of origin creates cultural and economic hardship for the family. In many Hispanic families, the father immigrates alone to establish a better economic future for the family. Estranged from the family, he may be at risk for such behavioral health risks as AIDS and alcohol abuse. Health issues may also arise because of low income and low self-esteem.

Acculturation is an important process in the adaptation, assimilation, or accommodation of immigrant groups to a new culture. This is sometimes referred to as hybridization. This is because in the process of adapting to a new culture, immigrants integrate the new culture into their beliefs and lifestyle and yet retain heritage consistency, maintaining pride in and adhering to their parent culture. According to the Theory of Orthogonal Cultural Identification, this process does not take place along a single continuum, but rather has numerous dimensions that operate independently from each other.26 Intergenerational gaps frequently develop because the youth become more quickly acculturated to the dominant society, and they may challenge the more traditional values, beliefs, and customs of their parents. This, in turn, may threaten the integrity and lines of respect in the family and roles within the family and society, particularly the role of women. Conflicts that arise from intergenerational gaps can lead to the alienation of young people and families from both the ethnic culture and the general dominant culture.

Gender Roles

All cultures develop socially sanctioned roles for respective genders. Over the past century, the social role for women in the United States has undergone many changes. The role of women has expanded from its traditional focus on child-bearing and child rearing to include participation in the workplace and marketplace. The feminist movement has championed this expanded role and has heightened consciousness about

opportunities consistent with the American values of individualism, equality, and political freedom. Furthermore, the feminist movement has challenged the values and structures developed by elite, masculine power, such as competition, strong focus on objectives and goals, the harnessing and control of nature, principle-based ethics, and productive activities. Feminists have promoted cultural practices and organizations that espouse more feminine values such as teamwork, focus on social process, working in harmony with nature, relationship-based ethics, and social connections. As people from other cultures move into the United States, these differing values and expanded roles for women may challenge the traditional family roles. In some cases where women’s roles take a more traditional position, a woman may need to get her husband’s or father’s permission prior to receiving medical care for herself or her children.

opportunities consistent with the American values of individualism, equality, and political freedom. Furthermore, the feminist movement has challenged the values and structures developed by elite, masculine power, such as competition, strong focus on objectives and goals, the harnessing and control of nature, principle-based ethics, and productive activities. Feminists have promoted cultural practices and organizations that espouse more feminine values such as teamwork, focus on social process, working in harmony with nature, relationship-based ethics, and social connections. As people from other cultures move into the United States, these differing values and expanded roles for women may challenge the traditional family roles. In some cases where women’s roles take a more traditional position, a woman may need to get her husband’s or father’s permission prior to receiving medical care for herself or her children.

Women have played significant roles in the healing arts as well. Historically and cross-culturally, women have discovered and preserved information about healing herbs and plants. In the Middle Ages, women were often persecuted for their knowledge of plants and other healing arts, which were deemed mysterious and suspicious. As medicine became more scientific and moved into a professional and scientific status, women were disengaged from the official healing roles.27 Women were associated with nature, and men with developing technology to tame and control nature. Women’s roles in the healing arts reflected this dichotomy. With the establishment of medical professions, women’s roles even in midwifery—a traditional role for women—were reduced, and physicians took over the practice and moved childbirth into hospitals. Women who worked in medical professions were often in nonphysician roles or positions of lower power and social status, such as nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. However, women have a strong presence among complementary healers and users of complementary therapies.28

Basic Value Orientations and Beliefs

All cultures hold certain value orientations that are central to their cultural patterns of behavior. These values can be both implicit and explicit. They influence an individual’s perception of others, direct that individual’s responses to others, and reflect his or her identity. These values are the basis for understanding oneself and one’s social relationships, political and economic structures, and direct and motivated behavior. These values are generally quite stable and do not change quickly. In a classic work on cultural orientations, Kluckhohn identifies five categories by which cultures address universal concerns of human nature:29

Innate human nature as being good, evil, or mixed

Humans’ relationship to nature as being subjugated to the forces of nature, harmonious coexistence with nature, or using human abilities to master nature

Relationship to time as past oriented, present oriented, or future oriented

Purpose of being seen as focused on selfrealization or a more action-orientation focus on doing

Relationship to other persons is expressed in individual, familial, or communal orientations

In Western culture and in particular the United States, these value orientations are reflected in a strong emphasis on individualism, mastery over nature, future-focused time orientation, and an action orientation to being. This can be seen in health care when we see the individual as the client and often ignore the family. Our mastery over nature is illustrated in our efforts to understand and cure disease and control health issues. Future orientation is reflected in our goal orientation and an emphasis on the effect our actions may have on the future. Both healthcare providers and clients expect some type of action or treatment from the clinical encounter. This reflects the shared value of an action-oriented culture. The healthcare system both influences and is influenced by the general cultural orientations. Cultural conflicts may occur when we fail to recognize that our clients hold differing value orientations.

Worldviews and cosmologies essential to Western Judeo-Christian-Islam beliefs differ from those of other world religions. Three dominant cosmology assumptions foundational to Western Judeo-Christian-Islam beliefs are monotheism, transcendence, and dualism.30 Monotheism, the belief in one God or Creator, who is

separate from humans, contrasts with the beliefs common in many agrarian societies, whose members believe in polytheism (i.e., multiple gods with different attributes) or pantheism (i.e., the locus of the sacred in all living things). The Western view of transcendence, or relating to God as separate from humans and knowing God through prayer, supplication, and rituals, can be contrasted with the Eastern view of immanence, or finding God by looking inward and doing other spiritual exercises to discover the sacred. Finally, Western dualism, separation of material from nonmaterial aspects of being, is in contrast to monism, or the essential unity found in both the pantheistic and Eastern belief systems. Many “new age” perspectives are exploring these issues as they are exposed to different cultural beliefs.

separate from humans, contrasts with the beliefs common in many agrarian societies, whose members believe in polytheism (i.e., multiple gods with different attributes) or pantheism (i.e., the locus of the sacred in all living things). The Western view of transcendence, or relating to God as separate from humans and knowing God through prayer, supplication, and rituals, can be contrasted with the Eastern view of immanence, or finding God by looking inward and doing other spiritual exercises to discover the sacred. Finally, Western dualism, separation of material from nonmaterial aspects of being, is in contrast to monism, or the essential unity found in both the pantheistic and Eastern belief systems. Many “new age” perspectives are exploring these issues as they are exposed to different cultural beliefs.

Technology and Culture

In contemporary Western culture, as well as in much of the world, technology is widely expanding. The development of technology affects values, religion, politics, and the arts and sciences. Medical technology in particular has progressed in its development of intricate instruments that allow for more complex procedures, such as computer-based imaging, microsurgery, gene mapping, targeted therapies, and pharmacogenomics. The development of these technologies poses new ethical and cultural questions related to the human and social impact this technology may have. Often the use of these technologies challenges existing cultural values. Once the technology is available for use, it often becomes the fuel for ethical debates related to such issues as allocation of resources, fetal tissue transplantation and right to life, and genetic testing and right to privacy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access