Creating Optimal Healing Environments

Mary Jo Kreitzer

Terri Zborowsky

Nurses have long been leaders in creating optimal healing environments (OHEs). Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, described the role of the nurse as helping the patient attain the best possible condition so that nature can act and self-healing can occur (Dossey, 2000). Nightingale recognized the nurse’s role in both caring for the patient and managing the physical environment. She wrote about the importance of natural light, fresh air, noise reduction, and infection control as well as spirituality, presence, and caring. Her philosophy embodied the notion that, as nurses, we don’t heal our patients: we recognize that healing occurs within a person and our work is to help people tap into their innate capacities.

Increasingly, a base of evidence about the creation of optimal healing environments is emerging from many disciplines, including nursing, interior design, architecture, neuroscience, psychoneuroimmunology, and environmental psychology, among others. Just as evidence-based practice informs clinical decision making, evidence-based design impacts the planning and construction of health care facilities. Nurses need to be taught about the ways in which the physical environment affects health outcomes. First, so that they can contribute to the design of patient care units and clinical facilities that will optimize the health and well-being of patients, their families, and the staff who work in health care environments. Second, nurses are in a unique position to carry on needed research on the impact of specific design interventions on intended outcomes.

DEFINITIONS

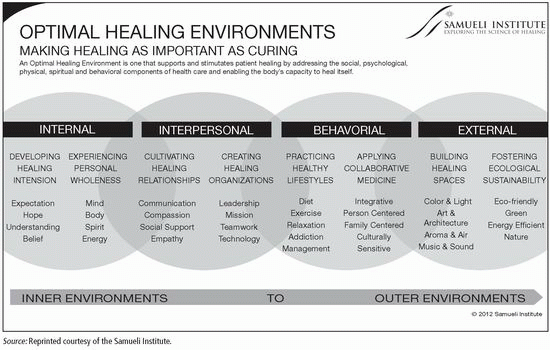

The word healing comes from the Anglo-Saxon haelen, meaning “to make whole.” Healing environments are designed to promote harmony or balance of mind, body, and spirit; to reduce anxiety and stress; and to be restorative. The Samueli Institute, a research center focused on the science of healing, defines an optimal healing environment as a place where all aspects of patient care—physical, emotional, spiritual, behavioral, and environmental—are optimized to support and stimulate healing (see Exhibit 5.1).

As illustrated in Exhibit 5.1, within an optimal healing environment, the internal resources—such as the expectations and hopes of all health care providers and of the patients themselves—are recognized as being important. There are opportunities for personal growth and self-care practices that promote wholeness. Healing relationships are cultivated as patients and their families interact with empathetic and compassionate health care providers and staff. A culture is created that supports healing through alignment of the organizational vision, mission, resources, and leadership. Healthy lifestyle behaviors are promoted and patients have options to choose conventional care and/or complementary therapies and healing practices. All of these elements are supported by a physical environment that embodies design characteristics known to promote healing: nature, light, and color, as well as fostering ecological sustainability.

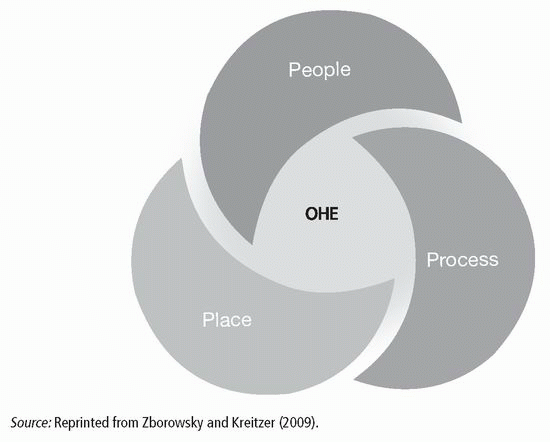

An OHE model developed by Zborowsky and Kreitzer (2009) and depicted in Exhibit 5.2 illustrates that an optimal healing environment is created through a deep and dynamic interplay among people, place, and process. In this model, people include the caregivers and support team that surround the patient. The characteristics and competencies of the staff and the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that they embody are some of the most critical elements of an OHE. The process element refers to the care processes as well as the leadership processes that support a culture that is aligned with creating an OHE. Care processes include conventional, integrative, and behavioral interventions. The place element focuses on the physical space where care is provided and the geography that surrounds the patient, family, and caregiver. Place elements include access to nature, positive distractions, aesthetics, the ambient environment, and ecosystem sustainability.

This model of OHE suggests that optimally, there is good coherence and alignment between the people (nurses and patients) who enact processes (caregiving in the context of patient-centered care) in a place (physical environment) that is designed to maximize positive patient outcomes. The reality is that much of care occurs in old, dysfunctional facilities. Even health care facilities built 20 years ago lack the available space and mechanical systems to function well today due to changes in building codes, guidelines, and best practice in care models. An inadequate space makes it more difficult to attain a truly healing environment, although

the elements of the caregiver and the care provided are even more critical than the physical place or space. Today, there is a better understanding and rigorous research that describes how to choose elements of place that support and enable an OHE.

the elements of the caregiver and the care provided are even more critical than the physical place or space. Today, there is a better understanding and rigorous research that describes how to choose elements of place that support and enable an OHE.

Exhibit 5.1. Optimal Healing Environments Make Healing as Important as Curing

|

Exhibit 5.2. People, Place, and Process: The Role of Place in Creating OHEs

|

The primary emphasis of this volume of Complementary & Alternative Therapies in Nursing is on the evidence and clinical applications of complementary and alternative therapies that nurses can use to enhance their practice. This chapter focuses on the dimension of place or space—the physical environment in which care is provided and the ways in which evidence can be used to create environments that contribute to positive health outcomes.

SCIENTIFIC BASIS

There is a growing body of evidence that links the physical environment to health outcomes. According to a review of the research literature on evidence-based health care design (Ulrich et al., 2008), there have been more than 1,000 rigorous empirical studies published that link the design of a hospital’s physical environment with health care outcomes. The studies cover a broad scope, with evidence linking:

Single-bed rooms with reduced hospital-acquired infections, reduced medical errors, reduced patient falls, improved patient sleep, and increased patient satisfaction

Decentralized supplies with increased staff effectiveness

Appropriate lighting with decreased medical errors and decreased staff stress, and

Ceiling lifts with decreased staff injuries

Although many of the studies focus on such topics as infection control, patient falls, staff productivity, and staff injuries, a growing number of studies focus on other aspects of the environment that contribute to healing.

As described by Malkin (2008), design strategies that focus on creating healing environments have in common the goal of reducing stress and include:

Connections to nature—artwork with a nature theme, views to the outside, interior gardens, plants

Options that give patients choices and control—room-service menu, choice of music and art, ability to control lighting and temperature

Spaces that provide access to social support—family zones within patient rooms that offer sleeping space, storage, and adequate seating

Positive distractions—music, water features, aviaries, videos of nature, aquariums, and sculpture

Reductions of environmental stressors such as noise and glare from direct light sources—carpet, indirect lighting, elimination of overhead paging

Theories Related to Healing Environments and Clinical Applications

Biophilia is the inherent human inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes. The concept, originally proposed by eminent biologist Edward O. Wilson (1984), has grown into a broader framework that increasingly is shaping the design of the man-made environment, including hospitals and other health care facilities. Biophilic design emphasizes the necessity of maintaining, enhancing, and restoring the beneficial experience of nature. It describes attempts to do so through the use of environmental features that embody such characteristics of the natural world as color, water, sunlight, plants, natural materials, and exterior views and vistas (Kellert, 2008).

The theory of biophilia has been empirically tested in clinical settings. Outcomes measured most often include stress and pain reduction. For example:

A study of elderly residents in an urban long-term-care facility revealed that they attached considerable importance to having access to window views of outdoor spaces with prominent features such as plants, gardens, and birds (Kearney & Winterbottom, 2005).

Patients in a dental clinic reported less stress on days when a large nature mural was hung in the waiting room, compared to days when there was no nature scene (Heerwagen, 1990).

In a prospective randomized trial of blood donors, it was found that donors who viewed a wall-mounted television playing a nature videotape had lower blood pressure and pulse rates than subjects who were viewing a television playing either a videotape of urban scenes or game or talk shows (Ulrich, Simons, & Miles, 2003).

Ulrich, Lunden, and Eltinge (1993) found that patients following heart surgery who viewed photos of trees and water required fewer doses of strong pain medication and reported less anxiety than patients who viewed abstract images or were assigned to a control group with no picture.

There is some evidence that the more engrossing a nature distraction, the greater the potential for pain alleviation. Miller, Hickman, and Lemasters (1992), in a study of burn patients, found that distracting patients during burn dressings by having them view nature scenes, accompanied by music, on a bedside television lessened both pain and anxiety. In a randomized prospective trial of patients undergoing bronchoscopy, those who viewed a ceiling-mounted nature scene and listened to nature sounds reported less pain than subjects in the control group who looked at a blank ceiling. Following a review of the literature on the use of virtual reality as an adjunct analgesic technique, Wismeijer and Vingerhoets (2005) concluded that “nature exposures” might tend to be more diverting—and hence pain-reducing—if they involved sound as well as visual stimulation and maximized realism and immersion. There is emerging research that uses a multimethod approach to understanding the effect nature has on patients. Goto, Park, Tsunetsugu, Herrup, and Miyazaki (2013) found that exposure to organized gardens can affect both the mood and cardiac physiology of elderly individuals. Among other findings, they revealed that a subject’s heart rate was significantly lower in the Japanese garden than in the other environments studied. The individual’s sympathetic function was significantly lower as well. In this case study of 19 patients in an assisted-living facility, the multimethod approach provided both qualitative and quantitative data.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree