Cranial Nerve Diseases

Mary M. Guanci

Certain cranial nerves (CNs) are especially vulnerable to injury because of their location within the cranial vault. CNs may be compressed by the vasculature or from a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor. Nerve function may also be affected by infectious processes such as herpes simplex or Lyme disease. The trigeminal (CN V), the facial (CN VII), the glossopharyngeal (CN IX), and the vagus (CN X) seem most vulnerable. The major cranial nerve diseases discussed in this chapter are: trigeminal neuralgia (TN), Bell’s palsy, Ménière’s disease, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia (GN). Acoustic neuromas are discussed in Chapter 20.

TRIGEMINAL NERVE

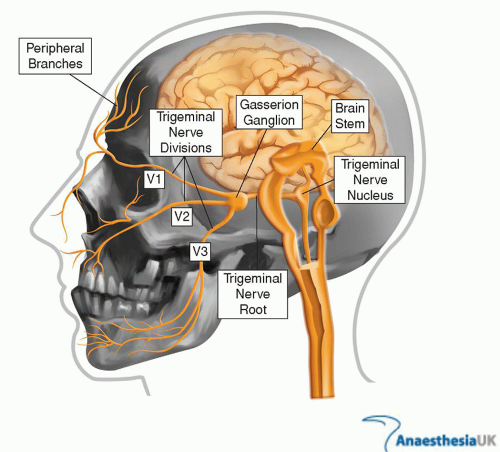

The trigeminal nerve is the fifth cranial nerve. The trigeminal nerve emerges from the pons, passing across the petrous ridge to become the Gasserian ganglion, which, in turn, separates into the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular divisions (Fig. 36-1). It is the largest of the cranial nerves, with both motor and sensory components. The sensory fibers relay touch, pain, and temperature sensations whereas the motor component innervates the temporal and masseter muscles used for chewing, jaw clenching, and lateral movement. The three branches of the nerve include the following.

Ophthalmic: forehead, eyes (including the cornea), nose, temples, meninges, paranasal sinuses, and part of the nasal mucosa

Maxillary: upper jaw, teeth, lip, cheeks, hard palate, maxillary sinus, and part of the nasal mucosa

Mandibular: lower jaw, teeth, lip, buccal mucosa, tongue, part of the external ear, auditory meatus, and meninges

Trigeminal neuralgia is a disease process that commonly affects these three divisions. See Figure 36-1.

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

Trigeminal neuralgia, formerly known as tic douloureux, is characterized by severe, unilateral, brief, stabbing, recurrent pain in the distribution to one or more branches of CN V. TN may be divided into two categories; idiopathic or classical and symptomatic. Idiopathic TN includes possible TN from vascular compression. Symptomatic TN is associated with tumors or diseases such as multiple sclerosis that affect the nerve ganglion.1 In TN, the second and third branches of the trigeminal nerve are about equally affected. Involvement of the first branch is rare, occurring in only about 10% of patients. When the ophthalmic branch is involved, the corneal reflex, a very important protective mechanism, may be lost.

Terms commonly used to describe TN pain are paroxysmal, sharp, piercing, lancing, shooting, burning, and lightning-like jabs. Status trigeminus, a rapid succession of tic-like spasms triggered by almost any stimuli, is a rare manifestation of the disease.

Most patients can identify trigger zones, which are small areas on the cheek, lip, gum, or forehead that initiate a bout of pain when stimulated. These trigger zones are sensitive to the most minimal of stimuli, such as touch, cold, pressure, or a blast of air. Chewing, talking, smiling, shaving, brushing the teeth, or going out of doors on a breezy day are common activities that may result in acute pain. TN may occur at any age, although it is most common in middle and later life. The incidence of TN is 4.3 per 1,00,000 persons per year, with a slightly higher incidence for women (5.9/1,00,000) compared with men (3.4/1,00,000).2

Although the etiology of TN is unclear, it is generally accepted that classic TN is a consequence of vascular compression and demyelination of the trigeminal nerve.3 Traumas, infection of the teeth or jaw, and flu-like illnesses have also been suggested as contributing to TN. An elongated, usually atherosclerotic artery adjacent to the trigeminal nerve can cause pressure on the nerve as it exits the brainstem. This pressure seems to be the etiology of TN for most patients. Compression by an aneurysm or neoplasm, arachnoiditis, or multiple sclerosis can also produce symptomatic TN. In making a diagnosis, other etiologies such as dental disease or temporomandibular joint dysfunction must be ruled out in order to initiate appropriate treatment.

The diagnosis of TN is based on the history and exclusion of other etiologies.4 The neurological examination is entirely normal except in the patient who has multiple sclerosis (MS) or a tumor that compresses the trigeminal nerve. The workup of TN will include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study and a magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA). Magnetic resonance angiography is used to visualize arterial vessels to aid in the rule out of vascular compression as an etiology.

Course of the Disease

Many individuals with TN experience bouts of pain for several weeks or months, followed by spontaneous remission. The length of remission varies from days to years. TN usually has an exacerbating and remitting course, and patients experience shorter periods of remission as they age. Growing neurosurgical data advocate the distinction of these two subtypes of TN into type 1 as defined as more than 50% episodic onset of TN pain and type 2 defined by more than 50% constant pain.5 The pain can cause much suffering

and limitation of the activities of daily living (ADLs). Because of the fear of pain, patients may not want to talk, eat, or attend to personal hygiene, such as washing the face, brushing the teeth, or shaving.6 Some people have become emaciated from not eating in their attempt to keep the face immobilized to prevent triggering pain. The evolvement of pain clinics offering comprehensive care of the patient with pain has offered support to people with TN.

and limitation of the activities of daily living (ADLs). Because of the fear of pain, patients may not want to talk, eat, or attend to personal hygiene, such as washing the face, brushing the teeth, or shaving.6 Some people have become emaciated from not eating in their attempt to keep the face immobilized to prevent triggering pain. The evolvement of pain clinics offering comprehensive care of the patient with pain has offered support to people with TN.

Treatment

Medical and surgical approaches are available to aid in the treatment of idiopathic TN. The preferred medical treatment for TN consists of anticonvulsant drugs, muscle relaxants, and neuroleptic agents. Evaluation of these treatments using large-scale placebo-controlled clinical trials is not available as yet. First tier approaches to treatment commonly include the use of carbamazepine. Carbamazepine may suppress or shorten the bouts of paroxysmal pain. Because carbamazepine can cause myelosuppression and liver damage, patients must be closely monitored with periodic complete blood counts (CBCs), liver enzymes, and liver function tests. If carbamazepine is not successful or is poorly tolerated, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, baclofen, phenytoin, and gabapentin alone or in combination are also prescribed.7 Since TN often occurs in the elderly population, monitoring of hepatic and renal function as well as drug-drug interactions should be considered when caring for these patients. Combination treatments using drug and surgical approaches are often successful in pain management. Peripheral blocks at the trigger points using agents such as ropivacaine, buvicane, and alcohol can provide temporary relief especially when combined with drug therapy.8

Surgical Procedures

For some, medical therapy gradually becomes less effective because of the progressive nature of the disease. Surgical options are then considered. These approaches include the Gasserian ganglion percutaneous techniques; radiofrequency thermocoagulation (RFTC), balloon compression (BC), and percutaneous glycerol rhizolysis (PGR) glycerol injections. These procedures require destruction of the myelinated fibers of the trigeminal nerve. Pain is relieved in an estimated 90% of the patients immediately, but reoccurrence of up to 50% has been reported. Facial numbness is the major side effect of these procedures which has been reported to greatly affect quality of life.9

The Gamma Knife (GK) uses gamma ray beams to perform stereotactic radiosurgery. The patient’s head is placed in a stereotactic frame and the beams are targeted on the proximal trigeminal nerve near the pons.10 Evidence has shown up to a 60% pain-free outcome with others requiring a combination of GK and drug therapy. New studies reveal the emergence of microvascular decompression (MVD) of the trigeminal root as the surgical treatment of choice. MVD is often considered as a first choice when a person has been refractory to pharmaceutical intervention. Outcome data have shown that 73% of patients can have a success rate, defined as pain free and no medications, for up to 15 years after intervention.11 An MRA aids in identification of the decompressive vessels which aids in surgical decision making. MVD is often performed as an endoscopically assisted craniectomy procedure. The endoscope allows for better visualization and minimizes the size of the craniectomy site. During the procedure, an approximate 1-inch area of cranial bone is removed. The endoscope is inserted and aids in examination of the area and the compressed vessel is moved or padded to ease compression. (Fig. 36-2 and Fig. 36-3). Because the craniectomy site is less than 1 inch, titanium plate replaces the craniectomy site and the incision closed. (Fig. 36-4). The endoscopic procedure has decreased length of stay to postoperative day one or two, depending on patient condition.

Nursing Management

Patients suffering from TN are often diagnosed and managed in an outpatient setting. TN can be very disabling and painful. Fear of triggering spasms may prevent an individual from engaging in

ADLs, social and recreational activities, and eating. A major role of the nurse is the assessment and management of pain. Nurses assist patients to identify trigger points, assess the frequency of spasms, assess the effectiveness of drug therapy, provide emotional support, and educate the individual in the ways to avoid triggering spasms. Consultations with the dietician, psychiatric nurse practitioner, social work, chaplaincy, and other team members will provide comprehensive support. Support and education of the patient’s family members and inclusion of the patient and family in the plan of care is important in maintaining and evaluating the plan of care. If the patient is a candidate for a surgical intervention, the nurse’s role in care is directed toward postoperative assessment and management.

ADLs, social and recreational activities, and eating. A major role of the nurse is the assessment and management of pain. Nurses assist patients to identify trigger points, assess the frequency of spasms, assess the effectiveness of drug therapy, provide emotional support, and educate the individual in the ways to avoid triggering spasms. Consultations with the dietician, psychiatric nurse practitioner, social work, chaplaincy, and other team members will provide comprehensive support. Support and education of the patient’s family members and inclusion of the patient and family in the plan of care is important in maintaining and evaluating the plan of care. If the patient is a candidate for a surgical intervention, the nurse’s role in care is directed toward postoperative assessment and management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree