Concepts of palliative care

Depending on the circumstances and the setting in which your patient dies, end-of-life care may last moments or months. It may involve complex drug regimens and near constant symptomatic care, or it may involve only honest, compassionate conversations with family members. Either way, you have acted to ease a patient’s transition from life to death.

Most Americans don’t die rapidly of a sudden illness. Instead, we’re more likely to be disabled for months or years by heart disease, emphysema, cancer, or another serious long-term illness. We have episodes of recurring complications, and we finally die “suddenly” as a result of an illness that has likely been present for years.

In the next 30 years, the number of older Americans will continue to grow at an increasing rate. In 2000, 4.2 million Americans were age 85 or older. By 2030, the baby-boom cohort of the 1950s will begin to hit age 85 and face the prospect of substantial disability. At that time, nearly 9 million Americans will be older than age 85 and will have some form of disease process that may lead to a discussion of end-of-life issues.

Your ability to incorporate the skills and the mindset of palliative care at the proper moment can help dying patients and their families attain a physically and spiritually peaceful death.

Defining palliative care

The notion of palliative care has existed for little more than a single generation. (See History of end-of-life care.) Even so, its tenets and benefits are becoming widely known. Many agencies and organizations have issued definitions for palliative care. They all have certain points in common. In general,

palliative care seeks to prevent and relieve suffering and to enhance the patient’s comfort and quality of life. It may be delivered alongside curative medical care, or it may be delivered alone as end-of-life care, seeking neither to delay nor hasten the patient’s death.

palliative care seeks to prevent and relieve suffering and to enhance the patient’s comfort and quality of life. It may be delivered alongside curative medical care, or it may be delivered alone as end-of-life care, seeking neither to delay nor hasten the patient’s death.

Especially in an end-of-life setting, palliative care seeks to ease all aspects of suffering, not just the physical ravages of disease or disability. For a dying patient, palliative care addresses psychological, spiritual, and practical issues in addition to those — such as pain or nausea — caused directly by a disease.

History of end-of-life care

| 1967 | Dame Cicely Saunders founds the first modern hospice — St. Christopher’s — in London and introduces the concept in the U.S. while lecturing at Yale. |

| 1969 | Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross publishes On Death and Dying, starting a grassroots movement in the U.S. |

| 1978 | The first U.S. hospice is founded in New Haven, Connecticut. |

| 1978 | National Hospice Organization (NHO) is founded. |

| 1980 | Congress establishes a 2-year demonstration program in 27 hospices to test improved health care for terminally ill patients. |

| 1982 | Congress passes the Medicare Hospice Benefit under Medicare Part A. |

| 1987 | Hospice Nurses Association (HNA) is formed. |

| 1990 | World Health Organization defines hospice and palliative care to set international standards. |

| 1990 | Congress passes the Patient Self-Determination Act, giving patients the right to advance directives and choices in their medical care. |

| 1994 | First nurses are certified as hospice specialists through the National Board for Certification of Hospice Nurses. |

| 1997 | HNA becomes the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. |

| 1999 | Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses begins. |

| 2000 | NHO becomes the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. |

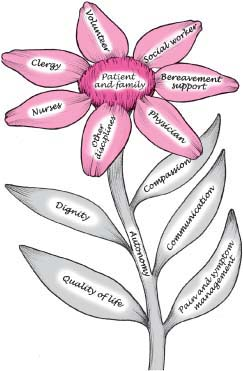

Typically, palliative care is provided by an interdisciplinary team on which a nurse plays a pivotal, personal role. Ideally, the nurse in collaboration with the palliative care team can address each of the patient’s and family’s needs. The patient and family are viewed as a single unit of care. Great emphasis is placed on meeting the patient’s needs and wishes, always in the context of the family as a unit.

When palliative care succeeds, the patient dies what some call a “good” death, free from avoidable distress and suffering, in keeping with his and his family’s wishes, and according to accepted clinical and ethical standards.

Philosophy of palliative care

In 1997, a task force sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation developed this philosophy of hospice and palliative care.

Palliative care provides support and care for persons facing life-threatening illnesses across settings.

Palliative care is based on the understanding that dying is a part of the normal life cycle.

The process of dying is a profound individual experience.

Care is focused on enhancing the quality of remaining life by integrating physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of care.

Use of an interdisciplinary team is the key to addressing the many needs of the dying and their families. (See Elements of palliative care.)

Interventions affirm life and neither hasten nor postpone death.

Through appropriate care and the promotion of a caring community, patients and families may be free to realize a degree of satisfaction and closure in preparing for death.

The nurse’s role

Expert nursing care is essential in end-of-life situations. (See Standards of hospice and palliative nursing care, page 6.) Of all the health care providers involved in end-of-life care, it’s the nurse who spends the most time with the patient and family. The nurse provides the type of care that allows patients and families to grow in the dying experience. Through expert nursing care, patients and families may experience the final phase of life as one that is healing, growth producing, even transformative.

Nurses have a wonderful opportunity to influence not only individual patients and families but also policy development in end-of-life care. Clinically, nurses are pivotal in providing symptom management. On a community and national level, nurses can lobby for progressive means to provide effective end-of-life care. This might include an expanded Hospice Medicare Benefit, more community resources for families unable to care for a terminally patient at home, and fundraising to support end-of-life care and education.

Terminally ill patients and their families deserve expert nursing care. By participating in the reality of end-of-life conditions, nurses accept the feelings of the individual. Caring for people in this phase of life acknowledges their deepest pain, legitimizes their experience, and gives them a feeling of personal integrity, wholeness, and value. As nurses discuss dying and death, they must do so in the context of hope, meaning, and continued growth and autonomy. In doing so, nurses continuously educate patients, families and others that death is a natural part of life.

Nurses are instrumental in ensuring that patients at the end of life are not abandoned. Nurses remain at the bedside, in the home, or in the nursing home. Nurses’ professional and personal ethics insist on acknowledging and honoring the patient’s wishes. Patients expect nurses to be available to them and, in doing so, nurses commit to experience the process with the patient. A core nursing function is to bear witness and be present with our patients as they move through the dying process and ultimately to help them find meaning in the experience. What is demanded of nurses is to provide

expert assessment, critical thinking, and symptom management with compassion and respect for the patient and his family.

expert assessment, critical thinking, and symptom management with compassion and respect for the patient and his family.

Standards of hospice and palliative nursing care

| Standard | Action |

|---|---|

| Assessment | Collect basic patient and family data. |

| Diagnosis | Analyze the assessment data and determine diagnoses using an accepted framework that supports hospice and palliative nursing knowledge. |

| Outcome identification | Identify expected outcomes relevant to the patient and family, in partnership with the interdisciplinary team. |

| Planning | Develop a plan of care—negotiated among patient, family, and interdisciplinary team—that includes interventions and treatments to attain expected outcomes. |

| Implementation | Implement the interventions identified in the plan of care. |

| Evaluation | Evaluate the patient’s and family’s progress in attaining expected outcomes. |

From Scope and Standards of Hospice and Palliative Nursing Practice, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association and American Nurses Association, 2002.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access