Complications of the Postpartum Period

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

major complications that can occur during the postpartum period, including risk factors for each

ways to identify complications based on key assessment findings

treatments that are appropriate for each complication

appropriate nursing interventions for each complication.

A look at postpartum complications

Although the postpartum period is a time of many physiologic and psychological changes and stressors, these changes are usually considered good changes—not unhealthy. During this time, the mother, the neonate, and other family members interact and grow as a family.

A cluster of complications

However, complications can develop due to a wide range of factors, such as blood loss, trauma, infection, or fatigue. Some common postpartum complications include postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum psychiatric disorders, puerperal infection, mastitis, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Your keen nursing skills can help to prevent problems or detect them early before they cause more stress or seriously interfere with the parent-child relationship.

|

Postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage—any blood loss from the uterus that exceeds 500 ml during a 24-hour period—is the major cause of maternal mortality. The danger of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony is greatest during the first hour after birth. During this time, the placenta has detached, leaving the highly vascular yet denuded uterus widely exposed. The risk continues to be high for 24 hours after birth.

After vaginal birth, blood loss of up to 500 ml is considered acceptable, although this amount may vary among health care facilities. The acceptable range for blood loss after cesarean birth is usually between 1,000 and 1,200 ml.

Complicating the matter

A patient who has a birth complicated by any of these factors should be observed for the possibility of developing a postpartum hemorrhage:

abruptio placentae

missed abortion

placenta previa

uterine infection

placenta accreta

uterine inversion

severe preeclampsia

amniotic fluid embolism

intrauterine fetal death

precipitous labor

macrosomia

multiple gestation

prolonged labor

multiparity.

What a difference a day makes

Postpartum hemorrhage is classified as early or late, depending on when it occurs. Early postpartum hemorrhage refers to blood loss in excess of 500 ml that occurs during the first 24-hours postpartum. Late postpartum hemorrhage refers to uterine blood loss in excess of 500 ml that occurs during the remaining 6-week postpartum period but after the first 24 hours.

What causes it

Uterine atony, lacerations, retained placenta or placental fragments, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) are the leading causes of postpartum hemorrhage.

|

Relax—don’t do it!

The primary cause of postpartum hemorrhage, especially early postpartum hemorrhage, is uterine atony (uterine relaxation). When the uterus doesn’t contract properly, vessels at the placental site remain open, allowing blood loss. Any condition that interferes with the ability of the uterus to contract can lead to uterine atony and, subsequently, postpartum hemorrhage. (See Relaxation is risky.)

Blame it on lacerations

Lacerations of the cervix, birth canal, or perineum can also lead to postpartum hemorrhage. Cervical lacerations may result in profuse bleeding if the uterine artery is torn. This type of hemorrhage usually occurs immediately after delivery of the placenta while the patient is still in the delivery area. Suspect lacerations when bleeding persists but the uterus is firm.

Stuck on you

Entrapment of a partially or completely separated placenta by an hourglass-shaped uterine constriction ring (a condition that prevents the entire placenta from expelling) can cause placental fragments to be retained in the uterus. Poor separation of the placenta is common in preterm births of 20 to 24 weeks’ gestation.

The reason for abnormal adherence is unknown, but it may result from the implantation of the zygote in an area of defective endometrium. This abnormal implantation leaves a zone of separation between the placenta and the decidua. If the fragment is large, bleeding may be apparent in the early postpartum period. If the fragment is small, however, bleeding may go unnoticed for several days, after which time, the woman suddenly has a large amount of bloody vaginal discharge.

To clot or not to clot

DIC is a fourth cause of postpartum hemorrhage. Any woman is at risk for DIC after childbirth. However, it’s more common in women with abruptio placentae, missed abortion, placenta previa, uterine infection, placenta accreta, uterine inversion, severe preeclampsia, amniotic fluid embolism, or intrauterine fetal death.

|

Relaxation is risky

Risk factors for uterine atony include:

polyhydramnios

delivery of a macrosomic neonate, usually more than 4.1 kg (9 lb)

use of magnesium sulfate during labor

multiple gestation

delivery that was rapid or required operative techniques, such as forceps or vacuum suction

injury to the cervix or birth canal, such as from trauma, lacerations, or hematoma development

use of oxytocin to initiate or augment labor or prolonged use of tocolytic agents

dystocia (dysfunctional labor)

previous history of postpartum hemorrhage

use of deep analgesia or anesthesia

infection, such as chorioamnionitis or endometritis.

What to look for

Bleeding is the key assessment finding for postpartum hemorrhage. It can occur suddenly in large amounts or over time as seeping or oozing of blood. Expect a patient with postpartum hemorrhage to saturate perineal pads more quickly than usual.

Soft and boggy

When uterine atony is the cause, the uterus feels soft and relaxed. The bladder may be distended, displacing the uterus to the right or left side of midline and preventing it from contracting properly. The fundus may also be pushed upward.

A cut above

When a laceration is the cause of postpartum hemorrhage, you may notice bright red blood with clots oozing continuously from the site and a uterus that remains firm.

Left behind

Bleeding caused by a retained placenta or placental fragments usually starts as a slow trickle, oozing, or frank hemorrhage. In the case of retained placental fragments, also expect to find the uterus soft and noncontracting.

The fourth culprit: DIC

When the patient’s bleeding is continuous and uterine atony, lacerations, and retained placenta or fragments have been ruled out, coagulation problems may be the cause of the bleeding.

The shocking truth

If blood loss is sufficient, the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock, such as increasing restlessness, lightheadedness, and dizziness as cerebral tissue perfusion decreases. Inspection may also reveal pale skin, decreased sensorium, increased pulse rate, and rapid, shallow respirations. Urine output usually falls below 25 ml/hour. Palpation may disclose rapid, thready peripheral pulses and cool skin that becomes cold and clammy.

Auscultation of blood pressure usually detects a mean arterial pressure below 60 mm Hg and a narrowing pulse pressure. Capillary refill at the nail beds is delayed 3 to 5 seconds.

|

What tests tell you

Diagnostic testing reveals a decrease in hemoglobin level and hematocrit. The patient’s hemoglobin level typically decreases 1 to 1.5 g/dl and hematocrit drops 2% to 4% from baseline. If the patient

has retained placental fragments, you may also find that serum human chorionic gonadotropin levels are elevated.

has retained placental fragments, you may also find that serum human chorionic gonadotropin levels are elevated.

Coagulating the matter

When DIC is the cause of postpartum hemorrhage, platelet and fibrinogen levels are decreased and clotting times (prothrombin time [PT] and partial thromboplastin time [PTT]) are prolonged. Blood tests also reveal decreased fibrinogen levels and fragmented red blood cells (RBCs). Fibrinolysis increases and then decreases. Coagulation factors are decreased, with decreased antithrombin III, an increased D-dimer test, and a normal or prolonged euglobulin lysis time.

How it’s treated

Treatment of postpartum hemorrhage focuses on correcting the underlying cause and instituting measures to control blood loss and to minimize the extent of hypovolemic shock.

Pump up the tone

For the patient with uterine atony, initiate uterine massage. The goal is to increase uterine tone and contractility to minimize blood loss. If clots are present, they should be expressed. If the patient’s bladder is distended, she should try to empty her bladder because a distended bladder prevents the uterus from fully contracting. If these efforts are ineffective or fail to maintain the uterus in a contracted state, oxytocin (Pitocin) or methylergonovine (Methergine) may be given I.M. or I.V. to produce sustained uterine contractions. Prostaglandins (carboprost tromethamine) can also be given I.M. to promote strong, sustained uterine contractions.

Source search

If the uterus is firm and contracted and the bladder isn’t distended, the source of the bleeding must still be identified. Perform visual or manual inspection of the perineum, vagina, uterus, cervix, and rectum. A laceration requires sutures. If a hematoma is found, treatment may involve observation, cold therapy, ligation of the bleeding vessel, or evacuation of the hematoma. Depending on the extent of fluid loss, replacement therapy may be indicated.

Remove the stragglers

Retained placental fragments typically are removed manually or, if manual extraction is unsuccessful, via dilatation and curettage (D&C). If the placenta is adhered to the uterine wall or has implanted into the myometrium, a hysterectomy may need to be performed to stop uterine bleeding.

|

Supportive to specific

Successful management of DIC requires prompt recognition and adequate treatment of the underlying disorder. Treatment may be supportive (for example, when the underlying disorder is self-limiting) or highly specific. If the patient isn’t actively bleeding, supportive care alone may reverse DIC. Active bleeding may require administration of blood, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, or packed RBCs to support hemostasis.

Heparin (Hep-loc) therapy for DIC is controversial. It may be used early in the disease to prevent microclotting but may be considered a last resort in the patient who’s actively bleeding. If thrombosis occurs, heparin therapy is usually mandatory. In most cases, it’s administered in combination with transfusion therapy.

Making up for lost fluids

Emergency treatment relies on prompt and adequate blood and fluid replacement to restore intravascular volume and to raise blood pressure and maintain it above 60 mm Hg. Rapid infusion of lactated Ringer solution and, possibly, albumin or other plasma expanders may be needed to expand volume adequately until whole blood can be matched.

What to do

Close, frequent assessment in the hour following delivery is crucial to prevent complications or allow early identification and prompt intervention should hemorrhage occur.

Here are other steps you should take in case of postpartum hemorrhage:

|

Assess the patient’s fundus and lochia every 15 minutes for 1 hour after birth to detect changes. Notify the practitioner if the fundus doesn’t remain contracted or if lochia increases.

Perform fundal massage, as indicated, to assist with uterine involution. Stay with the patient, frequently reassessing the fundus to ensure that it remains firm and contracted. Keep in mind that the uterus may relax quickly when massage is completed, placing the patient at risk for continued hemorrhage.

If you suspect postpartum hemorrhage, weigh perineal pads to estimate blood loss.

Turn the patient onto her side and inspect under the buttocks for pooling of blood.

Inspect the perineal area closely for oozing from possible lacerations.

Monitor vital signs frequently for changes, noting trends such as a continuously rising pulse rate and a drop in blood pressure. Report changes immediately. (See Managing low blood pressure.)

Assess intake and output, and report urine output less than 30 ml/hour. Encourage the patient to void frequently to prevent bladder distention from interfering with uter ine involution. If she can’t void, you may need to insert an indwelling urinary catheter.

Advice from the experts

Advice from the expertsManaging low blood pressure

If the patient’s systolic blood pressure drops below 80 mm Hg, increase the oxygen flow rate and notify the practitioner immediately. Systolic blood pressure below 80 mm Hg usually results in inadequate coronary artery blood flow, cardiac ischemia, arrhythmias, and further complications of low cardiac output.

Another ominous sign

Notify the practitioner and increase the infusion rate if the patient has a progressive drop in blood pressure (30 mm Hg or less from baseline) accompanied by a thready pulse. This usually signals inadequate cardiac output from reduced intravascular volume. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness. As cerebral hypoxia increases, the patient becomes more restless and confused.

A shocking development

Here are the steps you should take if the patient develops signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock:

Begin an I.V. infusion with lactated Ringer solution delivered through a large-bore (14G to 18G) catheter.

Administer colloids (albumin) and blood products as ordered.

Monitor the patient for fluid overload.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection, such as increased temperature, foul-smelling lochia, or redness and swelling of the incision.

Record blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rates, and peripheral pulse rates every 15 minutes until stable.

Monitor cardiac rhythm continuously.

During therapy, assess skin color and temperature and note changes. Cold, clammy skin may signal continuing peripheral vascular constriction and progressive shock.

Monitor capillary refill and skin turgor.

Watch for signs of impending coagulopathy, such as petechiae, bruising, and bleeding or oozing from gums or venipuncture sites.

Anticipate the need for fluid replacement and blood component therapy, as ordered.

Obtain arterial blood samples to measure arterial blood gas (ABG) levels. Administer oxygen by nasal cannula, face mask, or airway to ensure adequate tissue oxygenation. Adjust the oxygen flow rate as ABG measurements indicate.

Obtain venous blood specimens as ordered for a complete blood count, electrolyte measurements, typing and crossmatching, and coagulation studies.

If the patient has received I.V. oxytocin for treatment of uterine atony, continue to assess the fundus closely. The action of oxytocin, although immediate, is short in duration, so atony may recur. Monitor for nausea and vomiting.

Monitor the patient for hypertension if methylergonovine is administered. This medication shouldn’t be administered if the patient’s baseline blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg or greater.

If the practitioner orders I.M. administration of prostaglandin, be alert for possible adverse effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, tachycardia, headache, fever, and hypertension.

Provide emotional support to the patient, and explain all procedures to help alleviate fear and anxiety.

Monitor the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) for signs of hypoxia (decreased LOC).

Prepare the patient for possible treatments, such as bimanual massage, surgical repair of lacerations, or D&C.

Postpartum psychiatric disorders

Three distinct psychiatric disorders have been recognized during the postpartum period: postpartum blues (or baby blues), postpartum depression, and postpartum psychosis.

Blue, blue, my world is blue

Baby blues are the most common of the postpartum psychiatric disorders and the least severe. Approximately 50% of all postpartum women experience some form of baby blues. Baby blues usually occur within 3 to 5 days after birth. They are a normal, hormonally generated postpartum occurrence that is thought to foster maternal-neonatal attachment. Mothers who have delivered prematurely and those who have an infant in the newborn intensive care unit are at particularly high risk.

From blue to black

Postpartum depression and postpartum psychosis are mood disorders recognized by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Approximately 400,000 women a year (10% to 20% of postpartum women) develop postpartum depression or postpartum psychosis.

Postpartum depression

Postpartum depression affects as many as 15% of new mothers. This number may be higher because many cases probably aren’t reported due to the stigma of a psychiatric illness. Not only does postpartum depression interfere with the mother-infant relationship, it is thought to also interfere with child development and the relationship the child has with other children, family, and friends.

What causes it

The exact cause is unknown, but some prenatal risk factors may contribute to the development of postpartum depression.

|

A major key

A major risk factor for developing postpartum depression is a previous history of depression or a psychiatric illness before or during the pregnancy. Anxiety during the pregnancy, a teenage pregnancy, multiple births, lack of social support, stressful life situations other than the pregnancy, and conflict with a spouse or significant other during the pregnancy can also be major risk factors.

A minor key

Some minor risk factors include the socioeconomic status of the mother and obstetric complications.

The result

Untreated depression during pregnancy can lead to poor self-care; noncompliance with prenatal care; a negative effect on maternalinfant bonding; a higher risk of obstetric complications; drug, tobacco, or alcohol abuse; termination of the pregnancy; and suicide.

What to look for

Some distinct signs and symptoms help distinguish postpartum depression from postpartum baby blues, including:

feeling sad or down

decreased interest in normal activities

appetite problems and weight changes

anxiety and agitation

difficulty sleeping

fatigue and reduced energy

feeling guilty or worthless

feelings of suicide or thoughts of harming the infant.

The earliest postpartum depression is diagnosed in 2 weeks after birth and can occur at any point during the first year.

What tests tell you

There are no specific diagnostic tests for postpartum depression, but women can be screened during the prenatal period for risk factors leading to the development of postpartum depression. One such screening method is the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory. (See Postpartum depression predictors inventory (PDPI)-revised, pages 464 and 465.) Women can also be screened 2 weeks after delivery or later using the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) that is diagnostic for postpartum depression.

How it’s treated

Treatment can usually be accomplished on an outpatient basis. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac), and sertraline (Zoloft), are prescribed. These agents are thought to be safe for breast-feeding women.

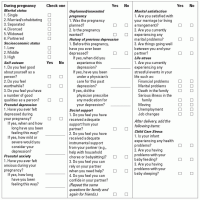

Postpartum depression predictors inventory (PDPI)-revised

The PDPI-Revised identifies risk factors for which nursing interventions can be planned to address each mother’s problems. The first 10 predictors can be assessed during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The last three risk factors are assessed after a mother has delivered.

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access