Complications of Labor and Birth

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

various complications that can occur with labor and birth

ways to assess and detect problems occurring with labor and birth

treatment and management of various complications.

A look at complications

Although labor usually proceeds without problems, about 8% of births involve complications. A problem can arise at any point in the labor process and can involve uterine contractions, the fetus, or the birth canal.

Stress stresses, honesty works

Emotional support is essential for the mother and her birthing partner during labor and birth. Even when labor and birth progress normally, the process is stressful and usually lengthy. It’s important to periodically assure the laboring woman that everything is going well and that she and the fetus are fine, as appropriate. When a complication arises, stress increases and honesty and sincerity remain just as important.

The importance of being careful

|

Because complications can occur at any point in the process, the mother and fetus need to be carefully monitored. Careful monitoring of the mother and fetus is important for several reasons. A malpositioned fetus is a major factor in birth complications. Nurses can be instrumental in identifying a malpositioned fetus by using Leopold maneuvers and prevent complications. For example, early detection of signs and symptoms of uterine rupture can help decrease maternal morbidity

during labor, such as changes in the fetal heart rate tracing. When working with a monitoring device, be sure to explain its importance to the patient and her partner. (See Tips for continuous electronic monitoring.)

during labor, such as changes in the fetal heart rate tracing. When working with a monitoring device, be sure to explain its importance to the patient and her partner. (See Tips for continuous electronic monitoring.)

C is for “complication”

In addition to problems arising from the condition of the mother or fetus, medical interventions to prevent or manage complications can cause other problems. One of the most invasive of these interventions is cesarean birth, in which a surgical incision is made in the abdominal and uterine walls for delivery of the neonate. Because this procedure is commonly performed, many times as a result of other complications, it’s listed below with other birth complications.

Amniotic fluid embolism

Amniotic fluid embolism occurs as rarely as 1 in 8,000 births. Occurring during labor or during the postpartum period, amniotic fluid embolism happens when amniotic fluid is forced into an open maternal uterine blood sinus due to some defect in the membranes themselves or after membrane rupture or partial premature separation of the placenta. Solid particles then enter the maternal circulation and travel to the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism. Amniotic fluid embolism isn’t preventable and requires prompt intervention and lifesaving treatment.

What causes it

The exact cause of amniotic fluid embolism is unknown, but possible risk factors include:

oxytocin administration

abruptio placentae

polyhydramnios.

How it’s detected

Advice from the experts

Advice from the expertsTips for continuous electronic monitoring

When applying an external electronic fetal and uterine monitoring device, remember to explain monitoring and why it must be used to the woman in labor to ensure compliance with the technology. Also, to avoid causing the patient distraction and stress, explain in advance that the alarms may sound even when everything is going smoothly.

Don’t forget

When reading the monitor pattern, remember:

to assess the mother and fetus to verify what the various patterns suggest

that the woman may move as a result of pain or a desire to adjust her position

that patient movement may result in artifacts on the tracings that require monitor adjustment.

Signs of amniotic fluid embolism are dramatic. The woman, who’s commonly in strong labor when the problem occurs, may sit up suddenly and grasp her chest. She may also complain of a sharp pain in her chest and an inability to breathe. In assessment, her color markedly pales and then turns the typical

bluish gray associated with pulmonary embolism and lack of blood flow to the lungs.

bluish gray associated with pulmonary embolism and lack of blood flow to the lungs.

What to do

Prognosis of the mother and fetus depends on the size of the emboli and the skill and speed of the emergency interventions. Immediate management of this complication includes oxygen administration by face mask or cannula. Because vital organs are deprived of oxygen supply due to the emboli, within minutes, the woman develops cardiopulmonary arrest, necessitating cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Even so, CPR may be ineffective because, despite providing oxygen transport to organs, it does nothing to remove the emboli. If the emboli aren’t removed, blood can’t circulate to the lungs. Death may occur within minutes.

|

Here are some other facts you should consider:

Even if the initial insult (the emboli) is resolved, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is highly likely from the presence of particles in the bloodstream, further complicating the patient’s condition.

If the patient survives initial emergency procedures, she’ll need continued management (such as endotracheal intubation) to maintain pulmonary function and therapy with fibrinogen to counteract DIC.

Prompt transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) is necessary.

The prognosis for the fetus is guarded because reduced placental perfusion results from the severe drop in maternal blood pressure.

The fetus may be delivered immediately by cesarean birth or vaginally using forceps.

Cephalopelvic disproportion

A narrowing, or contraction, of the birth canal, which can occur at the inlet, midpelvis, or outlet, causes a disproportion between the size of the fetal head and the pelvic diameters, or cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). CPD results in failure of labor to progress.

|

Primary problems

Malpositioning can occur because the fetus’s head isn’t engaged in the pelvis. Malpositioning can lead to further

complications. For example, if membranes rupture, the risk of cord prolapse increases significantly.

complications. For example, if membranes rupture, the risk of cord prolapse increases significantly.

What causes it

A small pelvis is a major contributing factor in CPD. The small size of the pelvis may be the result of rickets in the early life of the mother, a genetic predisposition, or a pelvis that isn’t fully matured in a young adolescent.

A perfect fit

In primigravidas, the fetal head normally engages with the pelvic brim at weeks 36 to 38 of gestation. When this event occurs before labor begins, it’s assumed that the pelvic inlet is adequate. Engagement of the head proves that the head fits into the pelvic brim and indicates that the head will probably also be able to pass through the midpelvis and through the outlet. In CPD, the fetal head may be too large to fit or the overall fetal size may be prohibitively large (known as macrosomia, or a birth weight of more than 4,000 g [8.8 lb]).

Inlets and outlets

Inlet contraction occurs when the narrowing of the anteroposterior diameter (from the symphysis pubis to the sacral prominence) is less than 11 cm or a maxi mum transverse diameter (between the ischial spines) is 12 cm or less. In outlet contraction, the transverse diameter narrows at the outlet to less than 11 cm. The outlet measurement is the distance between the ischial tuberosities. Because this measurement is easy to take during the expectant mother’s prenatal visits, the health care team can anticipate and prepare for outlet contraction before labor begins.

Positional faux pas

Abnormal positions of the fetus can also cause CPD. Posterior, transverse, face, brow, or breech presentations can make it difficult or impossible for the fetal presenting part to fit through the pelvis.

Fetal faux pas

Fetal anomalies such as hydrocephalus, hydrops fetalis, and tumors of the fetal head can also result in CPD.

|

How it’s detected

When engagement doesn’t occur in a primigravida, a problem exists. This problem may be a fetal abnormality, such as a largerthan-usual head, or a pelvic abnormality, as in a smaller-thanusual pelvis. It’s important to note that engagement doesn’t usually occur in multigravidas until labor begins. In this situation, a previous delivery of a full-term neonate vaginally without problems is substantial proof that the birth canal is considered adequate.

Rule of mum

Every primigravida should have pelvic measurements taken and recorded before week 24. Based on these measurements and the assumption that the fetus will be of average size, a decision can be made about the possibility of vaginal delivery.

What to do

If the pelvic measurements are borderline or just adequate, especially the inlet measurement, and the fetal lie and position are good, the woman’s practitioner or nurse-midwife may allow a trial labor to determine whether labor can progress normally. A trial labor may be allowed to continue if descent of the presenting part and dilation of the cervix are occurring. In other words, normal labor and delivery are occurring and no complications have been detected.

Giving it a try

|

If trial labor is anticipated, the following nursing measures are important:

Monitor fetal heart sounds and uterine contractions continuously if possible to detect abnormalities promptly.

Make sure that the woman’s urinary bladder is kept as empty as possible, such as by urging her to void every 2 hours, to allow the fetal head to use all the space available, making delivery possible.

After rupture of the membranes, assess fetal heart rate (FHR) carefully. If the fetal head is still high, alterations in FHR may indicate an increased danger of prolapsed cord and fetal anoxia.

Monitor progress of labor. After 6 to 12 hours, if fetal descent and cervical dilation can’t be documented or fetal distress occurs at any time, the woman should be scheduled for a cesarean birth.

Keep in mind that a woman undertaking trial labor may feel she’ll be unable to complete the process, which may lead her to feel she’s being needlessly subjected to pain. Emphasize that it’s best for the baby to be born vaginally, if possible.

If the trial labor fails and cesarean birth is scheduled, explain why the procedure is necessary and why it’s a better alternative for the baby at that point.

A woman having a trial labor may feel as if she’s on trial herself. She may feel she’s being judged and may be self-conscious if labor doesn’t go as well as hoped.

When dilation doesn’t occur, the woman may feel discouraged and inadequate, as if she’s somehow at fault. A woman may not be aware how much she wanted the trial labor to work until she’s told that it isn’t working.

Remember to support the support person. He or she may also be frightened and feel helpless when a problem occurs.

Assure the parents that a cesarean birth isn’t an inferior method of birth. Remind them that it’s an alternative method. In this instance, it’s the method of choice, allowing them to achieve their goal of a healthy mother and a healthy child.

|

Cesarean birth

Also known as cesarean section or cesarean delivery, cesarean birth is one of the oldest surgical procedures known. It may be performed as a planned surgery or an emergency procedure when vaginal birth isn’t possible. (See Cesarean factors.)

Cesarean factors

Cesarean birth may be a planned or an emergency procedure. Factors that lead to cesarean birth may be maternal, placental, or fetal in nature.

Maternal

Cephalopelvic disproportion

Active genital herpes or papilloma

Previous cesarean birth by classic incision

Disabling conditions, such as severe gestational hypertension and heart disease, that prevent pushing to accomplish the pelvic division of labor

Placental

Placenta previa

Premature separation of the placenta

Fetal

Transverse fetal lie

Extremely low fetal size

Fetal distress

Compound conditions, such as macrosomic fetus in a breech lie

Follow the plan

A cesarean birth is usually planned when the patient has had a previous cesarean birth and a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) isn’t recommended. It’s considered elective because the patient and her practitioner choose the date that the cesarean birth will be performed based on her due date and the maturity of the fetus.

Still dangerous

Because it’s an invasive surgical procedure, cesarean birth is considered more hazardous than vaginal birth. Thus, it’s only performed when the health and safety of the mother or fetus are in jeopardy. In addition, cesarean birth is generally contraindicated when there’s a documented dead fetus. In this situation, labor can be induced to avoid an unnecessary surgical procedure.

On the rise

The incidence of cesarean birth is on the rise. In the United States, between 9% and 16% of pregnancies end in cesarean birth. In perinatal centers that care for mothers with high-risk deliveries, the rate has risen to as high as 25%. Some theories have attributed this rise to recent medical and technologic advances in fetal and placental surveillance and care. However, nurse-midwifery birthing services have a lower incidence of cesarean birth than more mainstream hospital services. Some suggest that the midwifery model of continuous support during labor may be a reason for the difference.

Other possible influences on the rising rate of cesarean birth include:

combination of the increasing safety of cesarean birth and the use of fetal monitors, which provide for early detection of fetal problems that would necessitate cesarean birth

practitioners becoming increasingly skilled in the procedure while not acquiring comparable experience in alternative methods, such as external cephalic version and exercises to encourage a breech presentation to move into a vertex presentation

doctors’ fears of malpractice suits, which may result when a fetus is allowed to be delivered vaginally and then discovered to have suffered anoxia

consumer demand.

Double trouble

|

Occasionally, a woman may refuse to submit to a cesarean birth. Because women have a right to decide if they’ll undergo surgery, the right to refuse the procedure is respected. In some instances,

however, a court order to go ahead with the procedure may be obtained when cesarean birth is seen as necessary for the life of the fetus as well as the mother. Nurses working in labor and delivery units should be aware of the opinion of their agency’s ethics committee on this issue and should also be aware of the proper channels to take should this situation arise.

however, a court order to go ahead with the procedure may be obtained when cesarean birth is seen as necessary for the life of the fetus as well as the mother. Nurses working in labor and delivery units should be aware of the opinion of their agency’s ethics committee on this issue and should also be aware of the proper channels to take should this situation arise.

|

Body system effects

Because cesarean birth requires a surgical procedure, it can result in systemic effects, including thrombophlebitis from interference in the body’s natural stress response as well as alterations in body defenses, circulatory function, organ function, self-image, and self-esteem.

Stress response

Whenever the body is subjected to stress, either physical or psychological, it responds by trying to preserve function of all major body systems. This response includes the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla. Norepinephrine release leads to peripheral vasoconstriction, which forces blood to the central circulation and increases blood pressure. Epinephrine causes changes resulting in:

increased heart rate

bronchial dilation

elevation of blood glucose levels.

These responses are considered normal and are elicited when the person is tensed. The body is then ready for action with an increased heart rate and lung function as well as glucose for energy.

Antagonize, not minimize

However, these responses may antagonize anesthetic action aimed at minimizing body activity in the mother undergoing a cesarean birth. In addition, the stress response may result in reduced blood supply to the patient’s lower extremities. The pregnant patient is prone to thrombophlebitis due to the stasis of blood flow; the stress response compounds this potential, greatly increasing the risk. Combined with other effects of stress on major body systems, the stress response can significantly increase the risks associated with surgery.

Altered body defenses

The skin is the first line of defense against bacterial invasion. When the skin is incised for a surgical procedure, as in cesarean birth, this important line of defense is automatically lost. In addition, if cesarean birth is performed after membranes have been ruptured for hours,

the woman’s risk of infection doubles. Of course, precautions should be taken to minimize the risk to the patient through strict adherence to sterile technique during surgery and the days following the procedure.

the woman’s risk of infection doubles. Of course, precautions should be taken to minimize the risk to the patient through strict adherence to sterile technique during surgery and the days following the procedure.

Altered circulatory function

During cesarean birth, blood vessels are incised, a consequence of even the simplest surgical procedure. A surgical wound results in blood loss that, if extensive, can lead to hypovolemia and decreased blood pressure. When blood pressure decreases, inadequate perfusion of body tissues results, especially if the problem isn’t recognized and corrected quickly. The amount of blood lost in cesarean birth is relatively high compared with vaginal birth. Pelvic vessels are usually congested with blood needed to supply the placenta. When pressure is placed on these vessels, blood loss occurs freely. During a vaginal birth, a woman may loose up to 500 ml of blood. This loss increases dramatically to 1,000 ml with a cesarean birth.

Altered organ function

Like any body organ, the uterus may respond to being manipulated, cut, or repaired with a temporary disruption in function. Pressure from edema or inflammation can occur as fluid moves into the injured area. This normal response can further impair function of the uterus. In addition, handling of the uterus may result in a decrease in its ability to contract, which can lead to postpartum hemorrhage. Because complications may not be evident during the procedure, close assessment of the uterus is required in the postoperative period as well as an assessment of total body function to determine the degree of disruption.

|

What about the other organs?

In addition to effects on the uterus, other organs may be directly affected. For example, to reach the uterus, the bladder must be displaced anteriorly. To perform the cesarean birth, pressure must be exerted on the intestine, possibly leading to paralytic ileus or halting of intestinal function. Because of these manipulating events, uterine, bladder, intestine, and lower circulatory function must be carefully assessed after a cesarean birth to detect complications early and avert potential problems.

Altered self-image or self-esteem

Surgical procedures almost always leave incisional scars that are noticeable to some extent afterward. In some situations, the resulting scar from a cesarean birth may be quite noticeable,

such as when a horizontal incision is performed across the lower abdomen. The appearance of this scar may cause the woman to feel self-conscious later. She may also experience decreased selfesteem. This decrease in self-esteem may stem from a belief that she’s marked as someone who can’t give birth vaginally.

such as when a horizontal incision is performed across the lower abdomen. The appearance of this scar may cause the woman to feel self-conscious later. She may also experience decreased selfesteem. This decrease in self-esteem may stem from a belief that she’s marked as someone who can’t give birth vaginally.

Incision types

Depending on the type of cesarean incision, a patient may be able to deliver vaginally after previously delivering by cesarean birth (VBAC), now known as trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). In 2010, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) updated its guidelines regarding TOLAC to determine which women can safely have a VBAC. Although there is an increased incidence with uterine rupture with TOLAC, the overall incidence of maternal mortality is higher in women undergoing cesarean section. However, VBAC remains an increasingly successful alternative to elective cesarean birth. The type of incision chosen depends on the presentation of the fetus and the speed with which the procedure can be performed. In general, there are two types of skin incisions: vertical or transverse (Pfannenstiel). Neither is indicative of the type of incision made into the uterus.

|

Vertical cesarean incision

In a vertical cesarean incision, rarely used in obstetrics today, the incision is made between the navel and symphysis pubis. It’s made high on the uterus in the case of a placenta previa to avoid cutting the placenta. The result of this incision type is a wide skin scar that runs through the active contractile portion of the uterus. This scarring pattern carries an additional risk of complication in future pregnancies. Because this type of uterine scar could cause uterine rupture during labor, it’s likely that the woman won’t be able to have a subsequent vaginal birth. (See Types of cesarean incisions.) This type of incision is done in times of emergency when time is of the essence.

Transverse cesarean incision

Types of cesarean incisions

|

Transverse, also known as Pfannenstiel incision, is the most common type of cesarean incision. Unlike the vertical incision, a transverse incision is made horizontally across the lower abdomen just over the symphysis pubis and occurs horizontally across the uterus just over the cervix. This incision type is also referred to as a bikini incision because even a low-cut bathing suit should cover it. Because it’s made through the nonactive portion of

the uterus, or the part of the uterus that contracts minimally, it’s less likely to cause rupture in subsequent labors. Thus, the lowsegment incision makes it possible for a woman to attempt VBAC. Other advantages of this incision type include:

the uterus, or the part of the uterus that contracts minimally, it’s less likely to cause rupture in subsequent labors. Thus, the lowsegment incision makes it possible for a woman to attempt VBAC. Other advantages of this incision type include:

decreased blood loss

ease of suturing

minimal postpartum uterine infection risk

decreased risk of postpartum gastrointestinal (GI) complications.

The downside

The major disadvantage of this incision is that it takes longer to perform. So if the cesarean must be done in a hurry, such as in an emergency, transverse incision becomes impractical because of time constraints.

No assumptions, please

Sometimes, a skin incision is made horizontally and the uterine incision is made vertically or vice versa. Thus, during a future pregnancy, don’t assume that a small skin incision indicates a small uterine incision.

What causes it

Cesarean birth is indicated when labor or vaginal birth carries an unacceptable risk for the mother or fetus, such as in CPD and transverse lie or other malpresentations. It may also be necessary if induction is contraindicated or difficult or if advanced labor increases the risk of morbidity and mortality.

|

The most common reasons for cesarean birth are:

malpresentation of the fetus (such as shoulder or face presentation)

evidence of fetal intolerance of labor stress

CPD in which the pelvis is too small to accommodate the fetal head

certain cases of toxemia or preeclampsia

previous cesarean birth, especially with a classic incision

inadequate progress in labor (failure of induction).

Fetus in distress

Conditions causing fetal distress can also indicate a need for cesarean birth. These conditions include:

living fetus with prolapsed cord

fetal hypoxia

abnormal FHR patterns

unfavorable intrauterine environment, such as from infection

moderate to severe rhesus factor (Rh) isoimmunization.

Mom needs help

Less commonly, maternal conditions may necessitate cesarean birth. These conditions include:

complete placenta previa

abruptio placentae

placenta accreta

malignant tumors

chronic diseases in the mother in which delivery is indicated before term

active genital herpes

umbilical cord prolapsed

previous classical (vertical) incision on the uterus either from previous cesarean section or myomectomy

cervical cerclage.

How it’s detected

Special tests and monitoring procedures provide early indications of the need for cesarean birth:

Magnetic resonance imaging or X-ray pelvimetry reveals CPD and malpositioning.

Ultrasonography shows pelvic masses that interfere with vaginal birth and fetal position.

Auscultation of FHR (by fetoscope, Doppler unit, or electronic fetal monitor) determines acute fetal intolerance of labor.

What to do

Caregivers must use their most effective communication skills to educate the patient and family. Allow the patient to ask questions, and educate the patient before each procedure is done and the rationale for any intervention. It is important to tell the patient what is being done, why it is being done, and what she may experience. Support of the significant other in the cesarean birth experience is also important. In preparation for cesarean birth, an anesthetic is administered. Patients may have general or regional anesthetic, depending on the extent of maternal or fetal distress. The woman is then positioned on the operating table. A towel may be placed under her left hip to help relocate abdominal contents so that they’re up and away from the surgical field. This can also assist in lifting the uterus off the vena cava, promoting better circulation to the fetus as well as maternal blood return.

Blocking bacteria as well as the view

A metal screen or some other type of shielding may be placed at the patient’s shoulder level and covered with a sterile drape.

This creates the surgical field area, that is, a sterile environment, as well serving as a courtesy to help obstruct the patient’s view of the necessary surgical incision. The drape prevents the flow of bacteria from the woman’s respiratory tract to the incision site. Placement of the drape also blocks the support person’s line of vision, preventing additional anxiety and fear that may arise from the sight of blood.

Support for the support

The support person is usually positioned at the mother’s head. The incision area on the patient’s abdomen is then scrubbed, and drapes are placed around the area of incision so that only a small area of skin is left exposed. In many cases, watching a cesarean birth is the first surgery the father or support person has witnessed. Thus, the person may be too overwhelmed by the whole event or too interested in the procedure to be of optimum support. He or she may become concerned about the amount of manipulation and cutting that occurs before the uterus itself is cut, assuming fetal distress isn’t extreme. Remember to prepare the patient and support person for what they might see. This can help avert too much shock or surprise as well as promote open discussion about how much they would like to see or not see.

The down side

|

Possible maternal complications of cesarean birth include:

respiratory tract infection

wound dehiscence

thromboembolism

paralytic ileus

hemorrhage

genitourinary tract infection

bowel, bladder, or uterine injury.

Before surgery

Preoperative care measures involve both the mother and fetus. Here are some measures you should take:

Assess maternal and fetal status frequently until delivery, as your facility’s policy directs.

If ordered, make sure that an ultrasound has been obtained. The practitioner may have ordered the test to determine fetal position.

Explain cesarean birth to the patient and her partner, and answer any questions they may have.

Provide reassurance and emotional support to help improve the self-esteem and self-concept of the mother and her partner.

Remember that a cesarean birth is commonly performed after hours of labor, resulting in an exhausted patient and partner. Be brief but clear and stress the essential points about the procedure.

For a scheduled cesarean birth, discuss the procedure with both parents and provide preoperative teaching.

Observe the mother for signs of imminent delivery.

Demonstrate use of the incentive spirometer and have the patient practice deep breathing. Review splinting measures to decrease incisional pain with deep breathing and coughing.

Restrict food and fluids after midnight if a general anesthetic is ordered to prevent aspiration of vomitus.

Prepare the patient by shaving her from below the breasts to the pubic region and the upper quarter of the anterior thighs as indicated. Scrub and shave the abdomen and the symphysis pubis as ordered.

Make sure the patient’s bladder is empty, use an indwelling urinary catheter as ordered, and check for flow and patency.

Tell the mother that the catheter may remain in place for 24 hours or longer.

Administer ordered preoperative medication.

Give the mother an antacid to help neutralize stomach acid if ordered.

Start an I.V. infusion for fluid replacement therapy using the patient’s nondominant hand if required. Use an 18G or larger catheter to allow blood administration through the I.V. if needed.

Make sure the practitioner has ordered typing and crossmatching of the mother’s blood and that two units of blood are available.

After surgery

Postoperative care measures of the mother and child include:

|

As soon as possible, allow the mother to see, touch, and hold her neonate, either in the delivery room or after she recovers from the general anesthetic. Contact with the neonate promotes bonding.

Check the perineal pad and abdominal dressing on the incision every 15 minutes for 1 hour; then every half-hour for 4 hours; every hour for 4 hours; and finally, every 4 hours for 24 hours.

Perform fundal checks at the same intervals. Gently assess the fundus.

Check the dressing frequently for bleeding, and report it immediately. Be sure to keep the incision clean and dry.

Monitor vital signs every 5 minutes until stable. Then check vital signs when you evaluate perineal and abdominal drainage.

The practitioner may order oxytocin mixed in with the first 1,000 to 2,000 ml of I.V. fluids infused to promote uterine contraction and decrease the risk of hemorrhage. Make sure the I.V. is patent and monitor the patient carefully for effects of the medication.

Monitor intake and output as ordered. Expect the mother to receive I.V. fluids for 24 to 48 hours.

Make sure the catheter is patent and urine flow is adequate. When the catheter is removed, make sure that the woman can void without difficulty and that urine color and amount are adequate.

Maintain a patent airway for the mother and the neonate.

Encourage the mother to cough and deep breathe and use the incentive spirometer to promote adequate respiratory function.

If a general anesthetic was used, remain with the patient until she’s responsive.

If regional anesthetic was used, monitor the return of sensation to the legs.

Help the mother to turn from side to side every 1 to 2 hours.

If ordered, show the patient how to administer patient-controlled analgesia.

Administer pain medication as ordered, and provide comfort measures for breast engorgement as appropriate.

If the mother wants to breast-feed, offer encouragement and help.

Recognize afterpains in multiparas and monitor the effects of pain medication. Timing of administration of pain medication and breast-feeding may need to be coordinated so that the neonate won’t receive as much of the sedating effect.

Promote early ambulation to prevent cardiovascular and pulmonary complications. Remember to assist the mother initially and make sure she doesn’t suffer from orthostatic hypotension. Warn her that lochia may flow freely when she moves from a supine to an upright position.

|

Going home

Home care instructions should also be provided to a patient who has had a cesarean birth, including:

Instruct the patient to immediately report hemorrhage, chest or leg pain (possible thrombosis), dyspnea, or separation of the wound’s edges.

Tell her to also report signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, difficulty urinating, and flank pain.

Remind the patient to keep her follow-up appointment.

At that time, she can talk to the practitioner about using contraception and resuming intercourse.

Fetal presentation or position

Problems can occur with the fetus’s presentation or position during labor and delivery. Although most fetuses move into the proper birthing position, alternative positions and presentations can occur, making vaginal delivery difficult and, in some situations, impossible.

Problematic presentations and positions

Some presentations and positions that can be problematic include occipitoposterior position, breech presentation, face presentation, and transverse lie. A fifth type of presentation, called brow presentation, is rarely seen. (See A briefing on brow presentation.)

Occipitoposterior position

In about one-tenth of labors, the fetal position may be posterior rather than the traditional anterior position. When this occurs, the occiput, assuming the presentation is vertex, is directed diagonally and posteriorly, right occipitoposterior or left occipitoposterior. In these positions, during internal rotation, the fetal head must rotate through an arc of approximately 135 degrees rather than the normal 90-degree arc.

This rotation through the 135-degree arc may not be possible if the fetus is above average in size or isn’t in good flexion or if contractions are ineffective. Ineffective contractions may occur in:

uterine dysfunction from maternal exhaustion

fetal head arrested in the transverse position (transverse arrest).

1-2-3 rotate!

If rotation through the 135-degree arc doesn’t occur but the fetus has reached the midportion of the pelvis, he may be rotated manually to an anterior position with forceps and then delivered. As an alternative, cesarean delivery may be preferred because the risk of a midforceps maneuver exceeds the risk of cesarean delivery. If midforceps are used for birth, the woman is at risk for reproductive tract lacerations, hemorrhage, and infection in the postpartum period.

A briefing on brow presentation

A brow presentation (the rarest of the presentations) may occur with a multipara or in an individual with relaxed abdominal muscles. Here are some key points about this type of presentation:

It almost invariably results in obstructed labor because the head becomes jammed in the brim of the pelvis as the occipitomental diameter presents.

Unless the presentation spontaneously corrects, cesarean birth is necessary to safely deliver the neonate.

Because brow presentation leaves extreme ecchymotic bruising on the neonate’s face and head, his parents may need additional reassurance that he’s healthy.

Breech presentation

Most fetuses are in a breech presentation early in pregnancy. However, in approximately 97% of pregnancies, the fetus turns to a cephalic presentation by week 38. Although the fetal head is the widest single diameter, the fetus’s buttocks (breech), plus the lower extremities, takes up more space. The fundus, being the largest part of the uterus, promotes fetal turning so that the buttocks and lower extremities are within it. Additionally, some evidence suggests that a breech presentation is less likely to occur if a woman assumes a knee-chest position for approximately 15 minutes three times per day during pregnancy.

Styles of breech from frank to complete

There are several types of breech presentations:

frank breech—in which the buttocks are the presenting part and the legs are extended and rest on the fetal chest

footling breech—which can be either one foot (single-footling) or both feet (double-footling breech) and the thighs or lower legs aren’t flexed

complete breech—in which the fetal thighs are flexed on the abdomen and both the buttocks and the tightly flexed feet are against the cervix.

Danger, danger

Breech presentation is more hazardous than a cephalic presentation because there’s a greater risk of:

fetal anoxia from a prolapsed cord

traumatic injury to the aftercoming head, which can result in intracranial hemorrhage or anoxia

fracture of the spine or arm

dysfunctional labor

early rupture of the membranes because of the poor fit of the presenting part

meconium aspiration (the inevitable contraction of the fetal buttocks from cervical pressure commonly causes meconium to be extruded into the amniotic fluid before birth).

Same stages

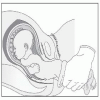

In a breech birth, the same stages of flexion, descent, internal rotation expulsion, and external rotation occur as in a cephalic birth. (See A look at breech birth, page 382.)

Turn, turn, turn

|

An alternative to vaginal or cesarean birth of a fetus in breech presentation is a method called external cephalic version, done at 36

to 38 weeks if the woman is not in labor. In this method, the fetus is manually turned from a breech to a cephalic position before birth. Use of external version can decrease the number of cesarean births due to breech presentations by about 40%. To turn the fetus:

to 38 weeks if the woman is not in labor. In this method, the fetus is manually turned from a breech to a cephalic position before birth. Use of external version can decrease the number of cesarean births due to breech presentations by about 40%. To turn the fetus:

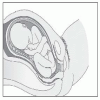

A look at breech birth

A breech presentation follows the same stages of descent, flexion, and rotation as a cephalic presentation.

As the breech fetus enters the birth canal, descent and external rotation occur, as shown below.

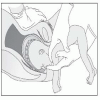

|

If the presenting part is the buttocks, the practitioner reaches up into the birth canal and pulls the legs down and out, as shown below. The breech delivery continues as the shoulders turn and present in the anteroposterior diameter of the mother’s pelvis.

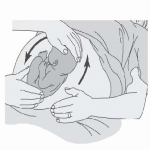

|

The head is then delivered by laying the neonate across the practitioner’s left hand while two fingers are placed in the neonate’s mouth and the other hand is placed on the back of the neck to apply gentle pressure to flex the head fully, as shown below. At the same time, gentle upward and outward traction is applied to the shoulders. An assistant may need to gently apply external abdominal wall pressure to ensure that head flexion occurs.

|

The breech and vertex of the fetus are located and grasped transabdominally by an examiner’s hands on the woman’s abdomen.

The breech and vertex of the fetus are located and grasped transabdominally by an examiner’s hands on the woman’s abdomen. Gentle pressure is then exerted to rotate the fetus. The fetus must be moved in a forward direction to a cephalic lie. (See A look at external cephalic version.)

Gentle pressure is then exerted to rotate the fetus. The fetus must be moved in a forward direction to a cephalic lie. (See A look at external cephalic version.)Face presentation

|

In a face presentation, the chin, or mentum, is the presenting part. Although this presentation is rare, when it does occur, birth usually can’t proceed because the diameter of the

presenting part is too large for the maternal pelvis. Face presentation is considered a warning sign because its cause is always some abnormality in the fetus or mother.

presenting part is too large for the maternal pelvis. Face presentation is considered a warning sign because its cause is always some abnormality in the fetus or mother.

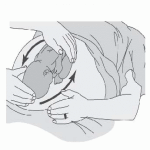

A look at external cephalic version

In external cephalic version, the practitioner manually rotates the fetus. The fetus is rotated by external pressure to a cephalic lie, aiding the possibility of a normal vaginal delivery.

Turning from breech position

|

Manipulating the fetus into cephalic lie

|

Transverse lie

Transverse lie occurs when the fetus lays horizontal to the uterus. Because there’s no firm presenting part, a vaginal delivery isn’t possible.

What causes it

Contributing factors depend on the specific fetal presentation or position abnormality.

Occipitoposterior position

Posterior positions tend to occur in women with these pelvic structures:

android pelvis

anthropoid pelvis

contracted pelvis.

Breech presentation

|

Breech presentation may occur for various reasons, including:

gestational age younger than 40 weeks

fetal abnormality from anencephaly, hydrocephalus, or meningocele

hydramnios, which allows free fetal movement so the fetus doesn’t have to engage for comfort

congenital anomaly of the uterus, such as a midseptum, that traps the fetus in a breech position

space-occupying mass in the pelvis that doesn’t allow engagement, such as a fibroid tumor of the uterus and placenta previa

pendulous abdomen in the mother that occurs when the abdominal muscles are lax, which may cause the uterus to fall so far forward that the head comes to lie outside the pelvic brim, causing breech presentation

multiple gestation in which the presenting fetus can’t turn to a vertex position.

Face presentation

A fetus in a posterior position, instead of flexing the head as labor proceeds, may extend the head, resulting in a face presentation. The situations in which this occurs include:

a woman with a contracted pelvis

placenta previa

relaxed uterus of a multipara

prematurity

hydramnios

fetal malformation.

Transverse lie

Transverse lie occurs in these conditions:

a woman with a pendulous abdomen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access