Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Eileen M. Stuart-Shor

Carol L. Wells-Federman

Esther Seibold

Nurse Healer OBJECTIVES

|

Theoretical

Define cognitive behavioral therapy.

Identify the three main principles of cognitive behavioral therapy.

Discuss the connection between cognition(s), health, and illness.

Identify four major contributors to the development of cognitive behavioral therapy.

Compare and contrast potential bio-psychosocial-spiritual-behavioral responses to stress and their effects on health and illness.

Discuss the roles of contracting and goal setting in cognitive restructuring.

Clinical

Discuss the major diagnoses and health problems that respond favorably to cognitive behavioral therapy.

Describe ways to facilitate cognitive restructuring.

Identify stress warning signals.

Describe and identify automatic thoughts.

Describe and identify cognitive distortions and irrational beliefs.

Describe a simple model for cognitive restructuring.

Outline the guidelines for organizing a cognitive behavioral therapy session.

Explore different practice settings in which cognitive restructuring can be used.

Personal

Identify stress warning signals.

In response to stress, stop, take a breath, reflect on the cause of the stress, and choose a more healthy response.

Develop a list of meaningful personal rewards.

Begin a healthy lifestyles and healthy pleasures journal.

DEFINITIONS

Cognition: The act or process of knowing.

Cognitive: Of or relating to consciousness, or being conscious; pertaining to intellectual activities (such as thinking, reasoning, imagining).

Cognitive behavioral therapy: A therapeutic approach that addresses the relationships among thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and physiology.

Cognitive distortions: Inaccurate, irrational thoughts; mistakes in thinking.

Cognitive restructuring: Examining and reframing one’s interpretation of the meaning of an event.

▪ THEORY AND RESEARCH

Historically, cognitive behavioral therapy is rooted in the treatment of anxiety and depression; however, in the last 10 years its application has broadened greatly. This chapter explores the application of cognitive behavioral therapy in the context of nursing practice along the wellness-illness continuum and the bio-psycho-social-spiritual domains. Cognitive behavioral therapy is integrated into expert nursing practice in myriad ways that are discussed throughout this chapter. In addition, the unique perspective that nurse healers bring to the application of cognitive behavioral therapy is addressed.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is based on the premise that stress and suffering are influenced by perception, or the way people think, and postulates that the thoughts that create stress are often illogical, negative, and distorted. These distorted negative thoughts can affect emotions, behaviors, and physiology and can influence the individual’s beliefs. By changing negative illogical thoughts, specifically those that trigger and perpetuate distress, the individual can change physical and emotional states.

In this chapter, to illustrate the relationship between illogical thoughts that trigger and perpetuate stress and changes in physical and emotional states we draw from the biopsychosocial model.1 The dimension of spirituality has been added to Engel’s existing model.2 In this eclectic bio-psycho-social-spiritual model, there is a tacit understanding that stress, or the perception of threat, can lead to changes in physical, emotional, behavioral, and spiritual states. If we accept that stress causes changes in physical and emotional states and is influenced by perception, and if we accept that perception is influenced by distorted thinking patterns (negative thoughts), then we have created a link between cognitive behavioral therapy, which restructures distorted, negative thinking patterns, and mind-body interactions, which influence health and illness. This link has implications for health promotion, symptom reduction, and disease management. Because understanding the dynamic interaction of cognitive behavioral therapy and the psychophysiology of mind-body connections is fundamental to the application of cognitive behavioral therapy in nursing, it is explored in greater detail later in this chapter.

Cognitive behavioral therapy was first used for depression and anxiety, as a short-term treatment that focused on helping people to recognize and change automatic, distorted thoughts that trigger and perpetuate distress.3 It is now being applied successfully to reduce health-risking behaviors, physical symptoms, and the emotional sequelae of a variety of illnesses to which stress is an important causative or contributing factor.4 Cognitive behavioral therapy is also useful in value clarification, which is the first step in establishing meaningful health goals.4 Cognitive behavioral therapy has ancient origins. A millennium ago, the Greek philosopher Epictetus described how people most often are disturbed not by the things that happen to them but by the opinions they have about those things. Theorists including Beck,5,6 Ellis,7,8 Meichenbaum,9 and Burns10,11 have advanced the modern interpretation of cognitive therapy. In the late 1960s, Beck conceptualized cognitive theory as a model to treat depression and anxiety and developed effective intervention strategies to restructure cognitive distortions and successfully mitigate the symptoms of depression and anxiety. Ellis developed the approach known as rational emotive therapy to recognize and challenge distorted thinking. He was particularly interested in uncovering those beliefs and assumptions that people hold as absolutes and that provide the lens (or filter of life experience) that causes distortions. Meichenbaum and Burns further enhanced the theory and practice of cognitive behavioral therapy through research and clinical experience.

Research on cognitive behavioral therapy continues to provide evidence of its broad application to both psychological and physical health problems. Beck, in a 40-year retrospective review of the current state of cognitive behavioral therapy, affirmed the utility of cognitive behavioral therapy (often referred to as cognitive therapy) in treating an array of psychological disorders and medical symptoms.12 A significant contributor to this extensive review, Butler and colleagues analyzed the current literature on outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).13 They provided a comprehensive assessment of 16 methodologically rigorous meta-analyses and focused on effect sizes that contrast outcomes for CBT with outcomes for

various control groups for each disorder. Large effect sizes were found for unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and childhood depressive and anxiety disorders. Effect sizes for CBT of marital distress, anger, childhood somatic disorders, and chronic pain were in the moderate range. CBT was somewhat superior to antidepressants in the treatment of adult depression. CBT was equally effective as behavior therapy in the treatment of adult depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

various control groups for each disorder. Large effect sizes were found for unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and childhood depressive and anxiety disorders. Effect sizes for CBT of marital distress, anger, childhood somatic disorders, and chronic pain were in the moderate range. CBT was somewhat superior to antidepressants in the treatment of adult depression. CBT was equally effective as behavior therapy in the treatment of adult depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

A recent meta-analysis of cognitive behavioral therapy,14 which compared CBT to other forms of psychotherapy, showed that CBT was superior to psychodynamic therapy among patients with anxiety or depressive disorders at both treatment and follow-up. No significant difference was identified between CBT and interpersonal or supportive therapies; however, the results suggest that CBT should be a first line of treatment for patients with anxiety and depressive disorders. An expert panel of mental health and public health researchers and practitioners has recommended CBT as an effective modality for treating depression in community-based older adults.15 This recommendation was made based on both the strength of evidence as well as feasibility and appropriateness for community-based delivery. A review and meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials of individuals treated within 3 months of trauma indicated that early trauma-focused CBT is more effective than supportive counseling in preventing chronic post-traumatic stress disorder.16

Evidence continues to grow in support of the application of cognitive behavioral therapy to treat a wide variety of physical symptoms. Authors have reported its effective use in the treatment of chronic low back pain,17 diabetes,18,19,20,21,22 insomnia,23,24 posttraumatic stress disorder,25 sleep-wake disturbance in cancer patients,26 chronic pain,27,28 fibromyalgia,29,30 migraine headache,31 spinal cord injuries,32 postconcussion syndrome,33 and chronic fatigue syndrome.34 In addition, it is found to be efficacious in the treatment of smoking in pregnant adolescents,35 alcohol abuse,36 binge eating,37 tinnitus,38 and teen cigarette smoking.39

Effects of Cognition on Health and Illness

Stress (the perception of a threat to one’s wellbeing, and the perception that one cannot cope) can cause physical, psychological, behavioral, and spiritual changes. Both cognition (the way one thinks) and perception (the way one views, interprets, or experiences someone or something) are important to an understanding of cognitive restructuring. If individuals change the way they think (cognition), they may change their perception of the situation. And if they change their perception of a situation so that they no longer view that situation as threatening, they may not experience stress. Thus, changing thoughts and perceptions can influence physiologic, psychological, behavioral, and spiritual processes. The following paragraphs delineate the effects of stress on physical, psychological, social, behavioral, and spiritual pathways.

Physiologic Effects of Stress

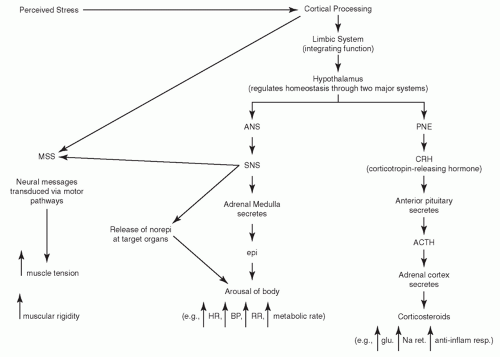

In response to a perceived threat (stress), the body gears up to meet the challenge. This perception of threat (stress) stimulates a cascade of biochemical events initiated by the central nervous system (Figure 11-1).40 Termed the fight-or-flight response41 and later the stress response,42 this heightened state of sympathetic arousal prepares the body for vigorous physical activity. Repeated exposure to daily hassles or prolonged stress activates the musculoskeletal system, increasing muscle tension. Concurrently, the autonomic nervous system, via the sympathetic branch, produces a generalized arousal that includes increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. In addition, there is a heightened awareness of the environment, shifting of blood from the visceral organs to the large muscle groups, altered lipid metabolism, and increased platelet aggregability.43 The neuroendocrine system, in response to stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the secretion of corticosteroids and mineralocorticoids, increases glucose levels, influences sodium retention, and increases the anti-inflammatory response in the acute phase. Over time, however, immune function decreases.40,44 In addition, there is evidence that levels of other hormones regulated by the neuroendocrine system, such as

reproductive and growth hormones, endorphins, and encephalins, can be affected.40

reproductive and growth hormones, endorphins, and encephalins, can be affected.40

More recently, chronic inflammation has been identified as one likely mechanism through which stress affects disease risk.45 For example, C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory marker, is emerging as a predictor of cardiovascular disease. McDade and colleagues investigated the contribution of behavioral and psychosocial factors to variation in CRP concentrations in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults.46 They found that psychosocial stresses, as well as health behaviors such as smoking, waist circumference, and latency to sleep, were important predictors of an increased concentration of CRP.

Prolonged or repeated exposure to stress has been shown to cause or exacerbate disease or symptoms of diseases such as angina, cardiac dysrhythmias, pain, tension headaches, insomnia, and gastrointestinal complaints. This influence is documented in extensive experimental and clinical literature.40 Stress has been found to influence the development of coronary artery disease in women47,48,49 and to influence pain perception in older adults.44

Psychological Effects of Stress

The psychological effects of stress are manifested by negative mood states such as anxiety, depression, hostility, and anger. These emotions (mood states) can in turn negatively influence a person’s

ability to concentrate and effectively problem solve. In addition, a growing body of research demonstrates the correlation between prolonged negative mood states and increased morbidity and mortality in several diseases.44,49,50,51 Doering and colleagues found that after bypass surgery, depressive symptoms were associated with an increase in infections, impaired wound healing, and poor emotional and physical recovery.49 Also, hostility has been found to play a role in a chronic cycle of inflammation among older adults and can dramatically affect their health.44

ability to concentrate and effectively problem solve. In addition, a growing body of research demonstrates the correlation between prolonged negative mood states and increased morbidity and mortality in several diseases.44,49,50,51 Doering and colleagues found that after bypass surgery, depressive symptoms were associated with an increase in infections, impaired wound healing, and poor emotional and physical recovery.49 Also, hostility has been found to play a role in a chronic cycle of inflammation among older adults and can dramatically affect their health.44

Concurrently, a growing body of research supports the importance of managing stress in the treatment of many diseases. Cancer52,53,54,55 and other diseases of the immune system have been shown to respond to interventions that reduce the stress response, as have arthritis,56,57 chronic pain,58 tension headaches,59,60 hypertension and heart disease,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68 asthma,69 insomnia,70 premenstrual syndrome, infertility,71,72,73 and the symptoms of chronic diseases.74,75,76

The benefits of developing a positive attitude and an optimistic explanatory style have been well documented. The link between optimism and health was made by researchers tracking the lives of a group of Harvard alumni who graduated in 1945. They found that individuals who were optimistic in college were healthier in later life, whereas those who were pessimistic were less healthy. By middle age, the pessimists experienced more health problems. A more recent study found that a pessimistic explanatory style was significantly associated with a self-report of poorer physical and mental functioning 30 years later.77 It is theorized that a pessimistic explanatory style or attitude, in addition to adversely affecting behavior, may weaken the immune system through a prolonged increase in sympathetic arousal. In addition, pessimists have more health-risking behaviors such as smoking, alcohol misuse, and sedentary lifestyle. Recognizing the influence of explanatory style on health and well-being furthers the understanding of how thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and physiology interact.

Social and Behavioral Effects of Stress

In response to stress, people often revert to less healthy behaviors.78,79 The social and behavioral pathway is best illustrated by appreciating the effect of behavior patterns on the incidence and progression of disease. How and what people eat, drink, and smoke, as well as how they take prescribed or illegal drugs, influence health. For many, stressful events can increase behaviors such as overeating or excessive intake of alcohol. As stress increases, self-control decreases. Lapsing to behaviors that provide immediate gratification is more likely when stress is high. This inability to control health-risking behaviors as a result of increased stress is called the stressdisinhibition effect.80

Behaviors such as social isolation that may be influenced by stress and negative thinking patterns have been shown to be associated with higher morbidity and mortality in the first year after myocardial infarction.81 Conversely, social support has been found to have a positive effect on health outcomes in medical settings. A report by Frasure-Smith and Prince revealed that among patients hospitalized for myocardial infarction, those receiving social support through nurses’ visits after discharge had a significantly lower risk of a second event compared with those in a control group.82 The authors theorized that positive changes in the emotional state of patients in the experimental group modulated the stress response.

Positive health outcomes in labor and delivery appear to be affected by emotional support as well. The most common surgical procedure performed in the United States is cesarean section (c-section). Delivery by c-section increases the risk of complications for mother and child, as well as extends the length of their hospital stay. The presence of a supportive woman during labor and delivery has been shown to reduce the need for c-section, shorten labor and delivery time, and reduce prenatal problems.83 Interestingly, greater benefits are realized when the provider is not a member of the hospital staff but rather a lay volunteer such as a female friend or family member taught supportive techniques.84 This implies obvious cost benefits and continues to underscore the implications of social support to both the patient’s health and the healthcare system.

Recent research on programs that influence behavior change have shown positive modification of some of the most widespread diseases. Lifestyle behavior change has been demonstrated to influence regression of coronary artery disease and reduce cardiac risk factors.64,85 These are

only a few of the hundreds of studies that provide continuing evidence of the multidirectional relationships among thoughts, feelings, beliefs, behaviors, and physiology.

only a few of the hundreds of studies that provide continuing evidence of the multidirectional relationships among thoughts, feelings, beliefs, behaviors, and physiology.

Spiritual Effects of Stress

In response to stress, people can become disconnected from their life’s meaning and purpose. In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl draws a parallel between connection with life’s meaning and survival.86 He describes the survivors of the World War II concentration camps as being those individuals who were able to retain their sense of meaning and purpose and were able to draw meaning and purpose from this experience. A feeling of disconnection, however, in addition to being an effect of stress, can also be a precursor to stress. Several studies have examined the effects of spirituality, defined as connection with life’s meaning and purpose, on health. Increased scores on measures of spirituality correlated with increased incidence of health-promoting behaviors.87 Other studies have explored the association between religious affiliation and health and have found a positive correlation.88,89,90 This area of study is of considerable interest in the scientific literature today.

▪ COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

In the preceding pages, a foundation has been established for how cognitions, which are exquisitely sensitive to perception, can influence physiologic, psychological, social and behavioral, and spiritual processes. Because of this influence, cognitive behavioral therapy is an important intervention in optimizing the positive links between mind, body, and spirit and in minimizing the negative consequences of adverse interactions. Cognitive behavioral therapy helps individuals reappraise or reevaluate their thinking. It is often referred to as cognitive restructuring because the intent of the intervention is to change or restructure the distortions in thinking patterns that cause stress. The basic principles of cognitive behavioral therapy are the following:11, 91,92

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access