Cirrhosis

A chronic hepatic disease, cirrhosis is characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease alters liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency.

Cirrhosis is the 11th most common cause of death in the United States and is most common among people ages 45 to 75. Most cases are a result of alcoholism, but toxins, biliary destruction, hepatitis, and a number of metabolic conditions may stimulate the destruction process.

Causes

There are several types of cirrhosis that vary with the etiology:

Laënnec’s or micronodular cirrhosis (alcohol or portal cirrhosis) stems from chronic alcoholism and malnutrition.

Postnecrotic or macronodular cirrhosis, which is usually a complication of viral hepatitis, may also occur after exposure to such liver toxins as arsenic, carbon tetrachloride, and phosphorus.

Biliary cirrhosis results from prolonged biliary tract obstruction or inflammation.

Idiopathic cirrhosis, which some patients develop, has no known cause.

Complications

Depending on the amount of liver damage, cirrhosis can lead to such complications as portal hypertension, bleeding esophageal varices, cardiomyopathy, GI ulcers, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, and death. (See What happens in portal hypertension, page 188.)

Life-threatening complications

Life-threatening complicationsWhat happens in portal hypertension

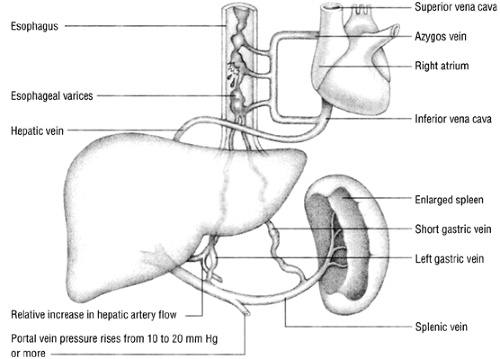

Portal hypertension—elevated pressure in the portal vein—occurs when blood flow meets increased resistance from fibrotic tissue that has developed as a result of diffuse destruction of hepatic cells. The disorder, a common result of cirrhosis, may also stem from mechanical obstruction and occlusion of the hepatic veins (Budd- Chiari syndrome).

As pressure in the portal vein rises, blood backs up into the spleen and flows through collateral channels to the venous system, bypassing the liver. Consequently, portal hypertension produces dilated tortuous collateral veins in the submucosa of the lower esophagus, known as esophageal varices.

Bleeding esophageal varices

In many patients, the first sign of portal hypertension is bleeding from esophageal varices. Esophageal varices commonly cause massive hematemesis that can quickly result in hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock. If the bleeding doesn’t stop, the patient will die.

Emergency interventions

If you suspect bleeding esophageal varices in a patient, follow these steps:

While you stay with the patient, send someone to notify the patient’s physician.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs continuously for signs of hypovolemic shock.

Prepare to administer vasopressin, 0.2 to 0.4 units/minute I.V., to reduce portal venous pressure.

Institute measures to alleviate hypovolemic shock, such as infusing blood or a crystalloid or colloid volume expander, as indicated.

Assist with gastric intubation and esophageal balloon tamponade.

Transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

If the patient continues to bleed or rebleeds, prepare to assist with sclerotherapy.

If the patient still continues to bleed, prepare to send him to the operating room for a portal systemic shunt insertion.

Assessment

Signs and symptoms are similar for all types, regardless of the cause. However, clinical manifestations vary depending on when in the course of the disease the patient seeks treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree