Cardiovascular care

Diseases

Acute coronary syndrome

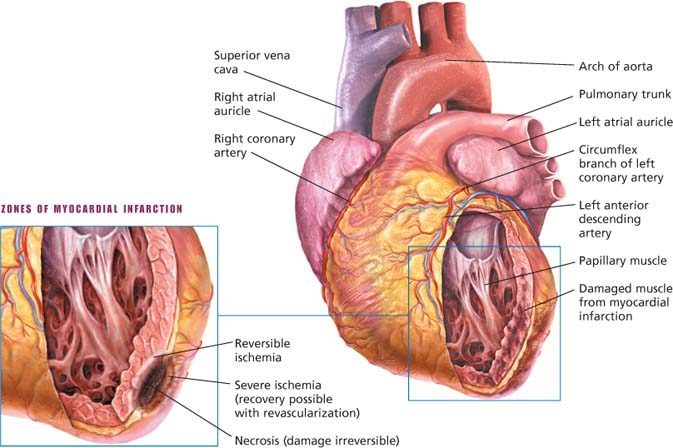

Acute myocardial infarction (MI), including ST-segment elevation MI, non-ST-segment elevation MI, and unstable angina are part of a group of diseases called acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Patients with ACS have some degree of coronary artery occlusion. Development begins with a rupture or erosion of plaque. The rupture results in platelet adhesions, fibrin clot formation, and activation of thrombin.

A thrombus progresses and occludes blood flow, although an early thrombus doesn’t necessarily block blood flow. The effect is an imbalance in myocardial oxygen supply and demand. Depending on the degree of occlusion, ACS is defined as three types.

If the patient has unstable angina, a thrombus partially occludes a coronary vessel. This thrombus is full of platelets. The partially occluded vessel may have distal microthrombi that cause necrosis in some myocytes.

If smaller vessels infarct, the patient is at higher risk for MI, which may progress to a non-Q-wave MI. Usually, only the innermost layer of the heart is damaged.

A Q-wave MI results when reduced blood flow through one of the coronary arteries causes myocardial ischemia, injury, and necrosis. The damage extends through all myocardial layers. The destruction of healthy cardiac tissue from myocardial ischemia varies with the severity of the ACS involved and the promptness of effective diagnosis and treatment.

Comparing signs and symptoms of unstable angina and MI

| Unstable angina | Myocardial infarction | |

|---|---|---|

| Character, location, and radiation |

|

|

| Duration of pain |

|

|

| Precipitating events |

|

|

| Relieving measures |

|

|

| Associated symptoms |

|

|

| Associated signs |

|

|

| Cardiac biomarkers |

|

|

The ABCs of ACS treatment

A—Antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockade

B—Beta-adrenergic blockers and blood pressure control

C—Cholesterol-lowering treatment and cigarette smoking cessation

D—Diabetes management and diet

E—Exercise

Treatment

For angina

Decrease in myocardial oxygen demand or increase in oxygen supply

For MI

Pain relief

Stabilization of heart rhythm

Revascularization of the coronary artery

Preservation of myocardial tissue

Reduction of cardiac workload

Thrombolytic therapy (unless contraindicated should be initiated within 30 to 60 minutes of arrival to emergency department)

Percutaneous coronary interventions should be performed within 90 minutes of arrival

Nursing considerations

Monitor and record the patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) readings, blood pressure, temperature, and heart and breath sounds.

Assess pain and treat appropriately as ordered. Record the severity, location, type, duration, and relief of pain.

Check the patient’s blood pressure after giving nitroglycerin, especially the first dose.

Continuously monitor ECG rhythm strips to detect rate changes and arrhythmias. Analyze rhythm strips, and place a representative strip in the patient’s chart if any new arrhythmias are identified, if chest pain occurs, or at least every shift or according to facility protocol.

During episodes of chest pain, obtain ECG readings and blood pressure and pulmonary artery catheter measurements, if applicable, to determine changes.

Assess for crackles, cough, tachypnea, and edema, which may indicate impending left-sided heart failure. Carefully monitor daily weight, intake and output, respiratory rate, serum enzyme levels, ECG readings, and blood pressure. Auscultate for adventitious breath sounds periodically (patients on bed rest typically have atelectatic crackles, which may disappear after coughing) and for S3 or S4 gallops.

Provide a stool softener to prevent straining during defecation, which causes vagal stimulation and may slow heart rate.

Provide emotional support to help reduce stress and anxiety.

After thrombolytic therapy, administer continuous heparin as ordered. Monitor the partial thromboplastin time every 6 hours, and monitor the patient for evidence of bleeding.

Monitor ECG rhythm strips for reperfusion arrhythmias and treat according to facility protocol.

Teaching about acute coronary syndrome

Teaching about acute coronary syndrome

Explain dosages and therapy to promote compliance with the prescribed medication regimen and other treatment measures.

Review dietary restrictions.

Encourage the patient to participate in a cardiac rehabilitation exercise program.

Counsel the patient to resume sexual activity progressively.

Advise the patient about appropriate responses to new or recurrent symptoms.

Advise the patient to report typical or atypical chest pain.

Stress the need to stop smoking. If necessary, refer the patient to a support group.

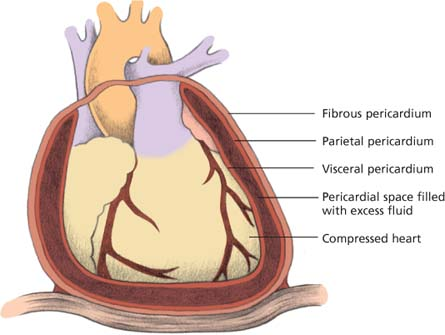

Aortic aneurysm

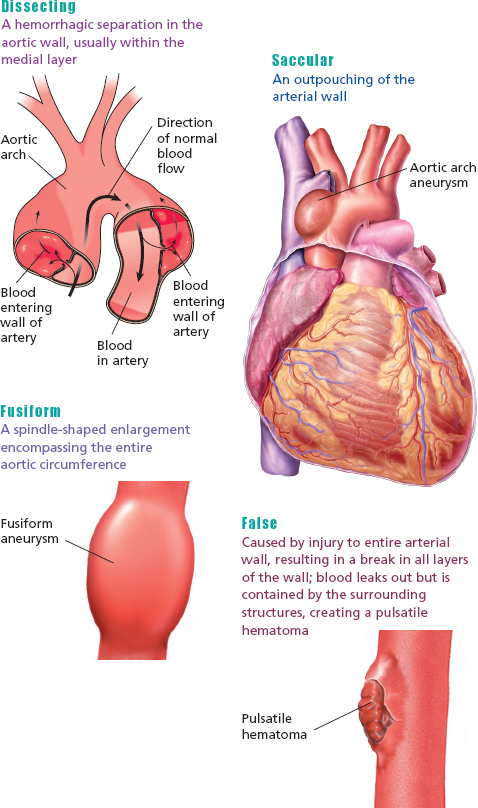

An aneurysm is a localized outpouching or abnormal dilation of a weakened arterial wall of the aorta. When developing, lateral pressure increases, causing the vessel lumen to widen and blood flow to slow. An aortic aneurysm may result in hemodynamic forces that can create pulsatile stresses on the weakened wall and press on the small vessels that supply nutrients to the arterial wall, causing the aorta to become bowed and torturous.

An aortic aneurysm may rupture or tear suddenly, possibly causing death. Rupture of an aortic aneurysm is a medical emergency requiring prompt treatment.

Aortic aneurysms are classified according to their anatomical location along the aorta, their shape, and how they are formed. Abdominal aneurysms are located along the portion of the aorta that passes through the abdomen. Ascending aneurysms are located in the ascending aorta and descending in the descending aorta.

Signs and symptoms

Abdominal

Lumbar pain radiating to flank and groin

Systolic bruit over aorta

Tenderness on deep palpation

Palpation of abdominal throbbing

Ascending

Bradycardia

Different blood pressures in right and left arms (more than 20 mm Hg)

Jugular vein distention

Murmur of aortic insufficiency

Pain

Pericardial friction rub

Unequal carotid and radial pulses

Descending

Dry cough

Dysphagia

Dyspnea and stridor

Hoarseness

Pain (sudden, between shoulder blades and chest)

Treatment

Small, asymptomatic aneurysms (less than 4 cm in diameter): monitoring every 6 months with ultrasonography, X-ray, or computed tomography

Large (5 cm or more) or symptomatic aneurysms: resection or repair to prevent rupture

Monitoring of blood pressure and treatment with antihypertensives as needed.

Nursing considerations

Allow the patient to express his fears and concerns. Help him identify effective coping strategies as he attempts to deal with his diagnosis.

Before elective surgery, weigh the patient, insert an indwelling urinary catheter and an I.V. line, and assist with insertion of the arterial line and pulmonary artery catheter to monitor hemodynamic balance.

In an acute situation

Insert multiple large-bore I.V. lines to facilitate blood replacement.

Prepare the patient for impending surgery.

As ordered, obtain blood samples for kidney function tests (such as blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels), a complete blood count with differential, blood typing and crossmatching, and arterial blood gas (ABG) levels.

Monitor the patient’s cardiac rhythm and vital signs. Assist with insertion of a pulmonary artery line to monitor for hemodynamic balance.

Administer ordered medications, such as an antihypertensive and a beta-adrenergic blocker to control aneurysm progression and an analgesic to relieve pain.

Be alert for signs of rupture, which may be fatal. Watch closely for any signs of acute blood loss (such as decreasing blood pressure, increasing pulse and respiratory rates, restlessness, decreased sensorium, and cool, clammy skin).

If rupture occurs, transport the patient to surgery as soon as possible. Medical antishock trousers may be used while transporting him to surgery.

Teaching about aortic aneurysm

Teaching about aortic aneurysm

Explain the surgical procedure and the expected postoperative care in the intensive care unit for patients undergoing open, complex abdominal surgery (I.V. lines, endotracheal and nasogastric intubation, and mechanical ventilation).

Instruct the patient to take all medications as prescribed and to carry a list of medications at all times, in case of an emergency.

Tell the patient not to push, pull, or lift heavy objects until the physician indicates that it’s okay to do so.

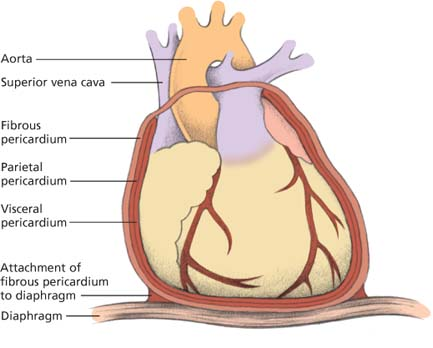

Cardiac tamponade

Cardiac tamponade is a rapid, unchecked increase in pressure in the pericardial sac. It usually results from blood or fluid that accumulates in the sac and compresses the heart. This compression obstructs blood flow to the ventricles and reduces the amount of blood pumped out of the heart with each contraction. Possible causes include malignant disease, dissecting aorta, heart surgery, trauma or radiation to the chest, heart tumor, placement of a central line, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, or a reaction to certain drugs, such as procainamide or hydralazine.

Signs and symptoms

Cardiac tamponade has three classic signs called Beck’s triad:

elevated central venous pressure (CVP) with jugular vein distention

muffled heart sounds due to fluid accumulation

pulsus paradoxus (inspiratory drop in systemic blood pressure greater than 15 mm Hg) due to arterial compression during inhalation.

Other symptoms include:

Chest pain or discomfort sometimes relieved by sitting upright or leaning forward

Pericardial friction rub

dyspnea and cough due to compressed trachea and bronchi

syncope, anxiety, and restlessness due to decreased oxygenation.

Treatment

Supplemental oxygen

Continuous electrocardiogram and hemodynamic monitoring

Pericardiocentesis

Surgical creation of pericardial window

Pericardectomy

Trial volume loading with crystalloids

Inotropic drugs, such as dobutamine

Posttraumatic injury: blood transfusion, thoracotomy to drain reaccumulating fluid, or repair of bleeding sites may be needed

Heparin-induced tamponade: heparin antagonist protamine sulfate to stop bleeding

Have emergency resucitation equipment at the bedside

Warfarin-induced tamponade: vitamin K to stop bleeding

Nursing considerations

After pericardiocentesis

Reassure the patient to reduce his anxiety.

Monitor blood pressure and CVP during and after pericardiocentesis. Infuse I.V. solutions, as ordered, to maintain blood pressure. Watch for a decrease in CVP and a concomitant increase in blood pressure, which indicate relief of cardiac compression.

Administer oxygen therapy as needed.

After thoracotomy

Give an antibiotic, protamine sulfate, or vitamin K as ordered.

Postoperatively monitor critical parameters, such as vital signs and arterial blood gas levels, and assess heart and breath sounds. Give an analgesic as ordered. Maintain the chest drainage system and be alert for complications, such as hemorrhage and arrhythmias.

Teaching about cardiac tamponade

Teaching about cardiac tamponadeExplain the procedure (pericardiocentesis or thoracotomy) to the patient. Tell him what to expect postoperatively (such as chest tubes, drains, and administration of oxygen). Teach him how to turn, deep breathe, and cough. If the patient isn’t in an acute situation, teach these techniques preoperatively.

Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart where the heart muscle tissue can’t work properly or as efficiently as it should. Cardiomyopathy can be classified as primary or secondary.

Primary cardiomyopathy refers to changes in the heart muscle without a specific cause. Secondary cardiomyopathy results from disorders that involve other organs as well as the heart.

There are four types of cardiomyopathy—dilated, restrictive, hypertrophic, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Dilated or congestive cardiomyopathy (most common) and restrictive cardiomyopathy are discussed here.

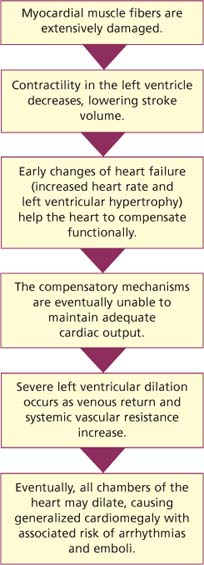

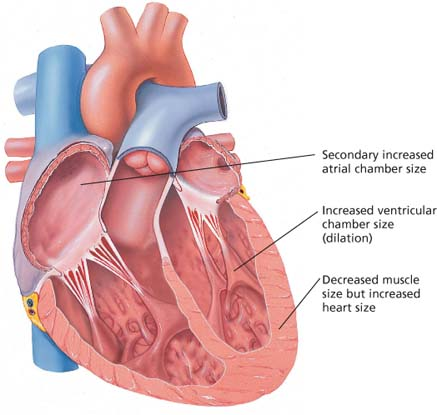

Cardiomyopathy, Dilated

Dilated cardiomyopathy results from extensively damaged myocardial muscle fibers. This disorder interferes with myocardial metabolism and grossly dilates all four chambers of the heart, giving the heart a globular appearance and shape. It usually isn’t diagnosed until it has reached an advanced stage, and the prognosis is generally poor.

Signs and symptoms

Shortness of breath, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, fatigue, and a dry cough at night caused by left-sided heart failure

Tachycardia with irregular pulse, if atrial fibrillation exists

Pansystolic murmur associated with mitral and tricuspid insufficiency

Peripheral cyanosis

Peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, jugular vein distention, and weight gain caused by right-sided heart failure

S3 gallop

Treatment

Management of underlying cause,

if known

Oxygen therapy

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors as first-line therapy

Diuretics

Digoxin (Lanoxin) for patients not responding to ACE inhibitors and diuretic therapy

Vasodilators, such as hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil)

Beta-adrenergic blockers for patients with mild or moderate heart failure

Antiarrhythmics such as amiodarone (Cordarone)

Cardioversion

Automatic implanted cardioverter-defibrillator insertion

Anticoagulants for patients with atrial fibrillation

Revascularization, such as coronary artery bypass graft surgery, if dilated cardiomyopathy is due to ischemia

Valvular repair or replacement if dilated cardiomyopathy is due to valve dysfunction

Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation; fluid restriction; low-fat, low-sodium diet; physical activity; and abstinence from alcohol

Left ventricular assist device

Nursing considerations

Alternate periods of rest with required activities of daily living and treatments. Provide personal care as needed to prevent fatigue.

Provide active or passive range-ofmotion exercises to prevent muscle atrophy.

Consult a dietitian to provide a low-sodium diet.

Monitor the patient for signs of progressive failure (decreased arterial pulses, increased jugular vein distention) and compromised renal perfusion (oliguria, increased blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels, and electrolyte imbalances). Weigh the patient daily.

Administer oxygen as needed.

If the patient is receiving a vasodilator, check his blood pressure and heart rate frequently.

If the patient is receiving a diuretic, monitor him for signs of resolving congestion (decreased crackles and dyspnea) or too-vigorous diuresis. Check his serum potassium level for hypokalemia, especially if therapy includes a cardiac glycoside.

Allow the patient and his family to express their fears and concerns.

Prevent constipation and stress ulcers to reduce cardiac workload.

Teaching about dilated cardiomyopathy

Teaching about dilated cardiomyopathy

Before discharge, teach the patient about the illness and its treatment.

Emphasize the need to restrict fluid and sodium intake, watch for weight gain, and take a cardiac glycoside if prescribed and watch for a toxic reaction to it (such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting).

Encourage family members to learn cardiopulmonary resuscitation because sudden cardiac arrest is possible.

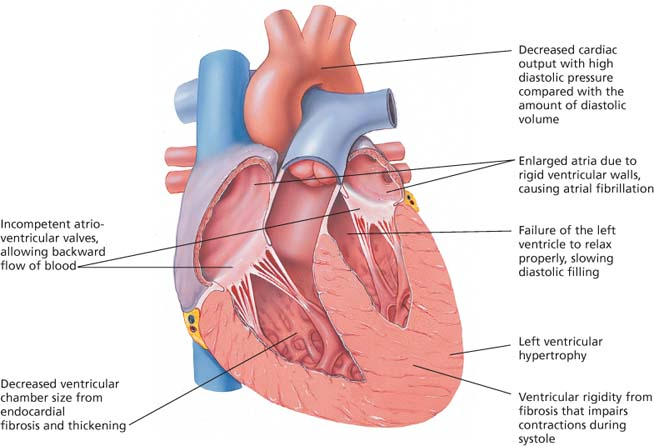

Cardiomyopathy, Restrictive

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is characterized by restricted ventricular filling (the result of left ventricular hypertrophy) and endocardial fibrosis and thickening. It’s severe and irreversible, and the average survival after diagnosis is 9 years.

Signs and symptoms

Fatigue

Chest pain

Dyspnea

Edema

High systemic and pulmonary venous pressure

Liver engorgement

Orthopnea

Abdominal distention

Palpitations

Treatment

Management of underlying cause (for example, administering deferoxamine to bind iron in restrictive cardiomyopathy due to hemochromatosis)

Digoxin (Lanoxin), diuretics, and a restricted-sodium diet to ease the symptoms of heart failure (although no therapy exists for patients with restricted ventricular filling)

Oral vasodilators

Pacemaker

Cardiac transplantation if intractable disease

Nursing considerations

In the acute phase, monitor heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure, urine output, and pulmonary artery pressure readings to help guide treatment.

Give psychological support. Provide appropriate diversionary activities for the patient restricted to prolonged bed rest. Because a poor prognosis may cause profound anxiety and depression, be especially supportive and understanding, and encourage the patient to express his fears. Refer him for psychosocial counseling, as necessary, for assistance in coping with his restricted lifestyle. Be flexible with visiting hours whenever possible.

Teaching about restrictive cardiomyopathy

Teaching about restrictive cardiomyopathyBefore discharge, teach the patient to watch for and report signs and symptoms of digoxin toxicity (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and yellow vision); to record and report weight gain; and, if sodium restriction is ordered, to avoid canned foods, pickles, smoked meats, and use of table salt.

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD) occurs when the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle harden and narrow. The result is the loss of oxygen and nutrients to myocardial tissue because of diminished coronary blood flow. This reduction in blood flow can lead to coronary syndrome (angina or myocardial infarction).

Signs and symptoms

Possibly none

Abnormal stress test or echocardiogram findings

Angina, typically with exertion or stress

Uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes mellitus

Major complications, such as acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, arrhythmias, or sudden death

Treatment

Drug therapy: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thrombolytics, diuretics, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, nitrates, beta-adrenergic or calcium channel blockers; antiplatelet, antilipemic, antihypertensive drugs

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

Minimally invasive surgery, an alternative to traditional CABG

Angioplasty

Arthrectomy

Stent placement (especially drug-eluding) to maintain patency of reopened artery

Lifestyle modifications to limit progression of CAD: smoking cessation, exercising regularly, maintaining ideal body weight, and eating a low-fat, low-sodium diet

Nursing considerations

During anginal episodes, monitor blood pressure and heart rate. Take a 12-lead electrocardiogram before administering nitroglycerin or other nitrates. Record the duration of pain, the amount of medication required to relieve it, and accompanying symptoms.

Ask the patient to grade the severity of his pain on a scale of 0 to 10.

Instruct the patient to call whenever he feels chest, arm, or neck pain.

After cardiac catheterization, review the expected course of treatment with the patient and family members. Monitor the catheter site for bleeding and check for distal pulses.

After percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and intravascular stenting, maintain heparinization, observe the patient for bleeding at the site, keep the affected leg immobile, and check for distal pulses. Precordial blood must be taken every 8 hours for 24 hours for cardiac enzyme levels. Complete blood count and electrolyte levels are monitored.

After rotational ablation, monitor the patient for chest pain, hypotension, coronary artery spasm, and bleeding from the catheter site. Provide heparin and antibiotic therapy for 24 to 48 hours as ordered.

After bypass surgery, monitor blood pressure, intake and output, breath sounds, chest tube drainage, and cardiac rhythm, watching for signs of ischemia and arrhythmias. Monitor capillary glucose, electrolyte levels, and arterial blood gases. Follow weaning parameters while patient is on a mechanical ventilator. I.V. epinephrine, nitroprusside, albumin, potassium, and blood products may be necessary. The patient may also need temporary epicardial pacing, especially if the surgery included replacement of the aortic valve.

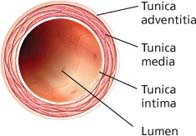

Understanding atherosclerosis

Understanding atherosclerosisCoronary arteries are normally flexible and can adapt to the oxygen-carrying needs of the heart.

|

Atherosclerosis causes a buildup of fatty fibrous plaque in the vessel walls. Thrombi can also form if the plaque ruptures through the intimal layer. The lumen becomes increasingly narrow.

|

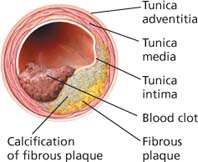

Stable angina

Angina is the classic sign of coronary artery disease. There are three forms of stable angina: chronic stable angina, microvascular (cardiac syndrome X) angina, and Prinzmetal’s (variant) angina.

Chronic stable angina

Characterized by exertional, rest-relieved discomfort, located anywhere between the umbilicus and the ears that may be associated with numbness of the arms or hands

Doesn’t increase in frequency or severity over time

Generally caused by fixed obstructive atheromatous lesions

Treated with rest and nitrates during attacks, and beta-adrenergic blockers for prevention

Microvascular (cardiac syndrome X) angina

Characterized by stable angina-like chest pain

Caused by impairment of vasodilator reserve

Poses no risk of cardiac ischemia because the capillaries are too small to block oxygenation of cardiac cells

Treated with nitrates, beta-adrenergic blockers, or calcium channel blockers

Prinzmetal’s (variant) angina

Characterized by resting discomfort, which can cause the patient to awaken at night and persists for hours

Caused by coronary artery vasospasm

Causes reversible ST-segment elevation during event

Treated with calcium channel blockers and nitrates, possibly beta-adrenergic blockers, or coronary stenting if intractable

Teaching about CAD

Teaching about CAD

If the patient is scheduled for surgery, explain the procedure, provide a tour of the intensive care unit, introduce him to the staff, and discuss postoperative care.

Help the patient determine which activities precipitate episodes of pain. Help him identify and select more effective coping mechanisms to deal with stress.

Stress the need to follow the prescribed drug regimen.

Encourage the patient to maintain the prescribed low-sodium diet and start a low-calorie diet as well.

Explain that recurrent angina symptoms after PTCA or rotational ablation may signal reobstruction.

Encourage regular, moderate exercise. Refer the patient to a cardiac rehabilitation center or cardiovascular fitness program near his home or workplace.

Reassure the patient that he can resume sexual activity and that modifications can allow for sexual fulfillment without fear of overexertion, pain, or reocclusion.

Refer the patient to a smoking cessation program.

Endocarditis

Endocarditis (also known as infective or bacterial endocarditis) is an infection of the endocardium, heart valves, or cardiac prosthesis resulting from bacterial or fungal invasion. Even transient bacteremia after dental or urogenital procedures can introduce the pathogen into the bloodstream. This infection causes fibrin and platelets to aggregate on the valve tissue and engulf circulating bacteria or fungi that flourish and form friable, wartlike vegetative growths on the heart valves, the endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the epithelium of a blood vessel. Such growths may cover the valve surfaces, causing ulceration and necrosis; they may also extend to the chordae tendineae, leading to rupture and subsequent valvular insufficiency. Ultimately, they may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, central nervous system, and lungs.

Untreated, endocarditis is usually fatal, but with proper treatment, 70% of patients recover. The prognosis is worst when endocarditis causes severe valvular damage, leading to insufficiency and heart failure, or when it involves a prosthetic valve.

Signs and symptoms

Weakness and fatigue

Anorexia

Arthralgia

Intermittent fever that may recur for weeks (in 90% of patients)

Weight loss

Loud, regurgitant murmur

Petechiae

Osler nodes

Asymmetrical arthritis

Treatment

Long-term antibiotic therapy: penicillin and aminoglycoside, usually gentamicin (Garamycin)

Adequate rest periods

Aspirin or acetaminophen for fever and aches

Sufficient fluid intake

Corrective surgery if refractory heart failure develops or heart structures are damaged

Replacement of infected prosthetic valve

Prophylactic treatment for high-risk individuals

Nursing considerations

Stress the importance of adequate rest. Assist the patient with bathing if necessary. Provide a bedside commode because using a commode puts less stress on the heart than using a bedpan. Offer the patient diversionary, physically undemanding activities.

To reduce anxiety, allow the patient to express his concerns about the effects of activity restrictions on his responsibilities and routines.

Before giving an antibiotic, obtain a patient history of allergies. Administer the prescribed antibiotic on time to maintain a consistent drug level in the blood.

Assess cardiovascular status frequently, and watch for signs and symptoms of left-sided heart failure, such as dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, crackles, and weight gain. Check for changes in cardiac rhythm or conduction.

Administer oxygen and evaluate arterial blood gas levels, as needed, to ensure adequate oxygenation.

Monitor the patient’s renal status (including blood urea nitrogen levels, creatinine clearance, and urine output) to check for signs of renal emboli and drug toxicity.

Teaching about endocarditis

Teaching about endocarditis

Teach the patient about the anti-infectives prescribed. Stress the importance of taking the medication and restricting activities for as long as the physician orders.

Tell the patient to watch closely for fever, anorexia, and other signs and symptoms of relapse after treatment stops.

Make sure the susceptible patient understands the need for a prophylactic antibiotic before, during, and after dental work, childbirth, and genitourinary, GI, or gynecologic procedures.

Teach the patient to brush his teeth with a soft toothbrush and rinse his mouth thoroughly. Tell him to avoid flossing his teeth and using irrigation devices.

Teach the patient how to recognize symptoms of endocarditis, and tell him to notify the physician immediately if such symptoms occur.

Heart failure

Heart failure is a syndrome characterized by myocardial dysfunction that leads to impaired pump performance (diminished cardiac output) or to frank heart failure and abnormal circulatory congestion. Heart failure can be classified according to its pathophysiology. It may be right-sided or left-sided, systolic or diastolic, and acute or chronic.

Congestion of systemic or venous circulation may result in peripheral edema or hepatomegaly; congestion of pulmonary circulation may cause pulmonary edema, an acute life-threatening emergency. Pump failure usually occurs in a damaged left ventricle (left-sided heart failure) but may occur in the right ventricle (right-sided heart failure) either as a primary disorder or secondary to left-sided heart failure. Sometimes, left- and right-sided heart failure develop simultaneously.

Left-Sided Heart Failure

Left-sided heart failure is the result of ineffective left ventricular contraction. It may lead to pulmonary congestion or pulmonary edema and decreased cardiac output. Left ventricular MI, hypertension, and aortic or mitral valve stenosis or insufficiency are common causes. As the left ventricle’s decreased pumping ability persists, fluid accumulates, backing into the left atrium, and then into the lungs. If this worsens, pulmonary edema and right-sided heart failure may also result.

Signs and symptoms

Dyspnea, initially on exertion

Confusion

Dizziness

Bibasilar crackles

Cough

Cyanosis or pallor

Fatigue

Muscle weakness

Tachycardia

Right-Sided Heart Failure

Right-sided heart failure is the result of ineffective right ventricular contraction. It may be caused by acute right ventricular infarction or pulmonary embolus. However, the most common cause is profound backward blood flow due to left-sided heart failure.

Signs and symptoms

Edema, initially dependent

Generalized weight gain

Hepatomegaly

Jugular vein distention

Ascites

Systolic or Diastolic

With systolic heart failure, the left ventricle can’t pump enough blood out to the systemic circulation during systole, and the ejection fraction fails. Consequently, blood backs up into the pulmonary circulation, pressure rises in the pulmonary venous system, and cardiac output fails.

With diastolic heart failure, the left ventricle can’t relax and fill properly during diastole, and the stroke volume fails. Therefore, larger ventricular volumes are needed to maintain cardiac output.

Acute or Chronic

The term acute refers to the timing of the onset of symptoms and whether compensatory mechanisms kick in. With acute heart failure, fluid status is typically normal or low, and sodium and water retention doesn’t occur.

With chronic heart failure, signs and symptoms have been present for some time, compensatory mechanisms have taken effect, and fluid volume overload persists. Drugs, diet change, and activity restrictions usually control symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment of underlying disorders may improve heart failure. Lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and dietary adjustments, are important. Medications are prescribed according to the classification of signs and symptoms and recommendations of the New York Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association.

Nursing interventions

Place the patient in Fowler’s position and give him supplemental oxygen to help him breathe more easily. Organize all activity to provide maximum rest periods.

Weigh the patient daily (the best indicator of fluid retention), and check for peripheral edema. Also, monitor I.V. intake and urine output (especially if the patient is receiving a diuretic).

Assess vital signs (for increased respiratory and heart rates and for narrowing pulse pressure) and mental status. Auscultate for abnormal heart and breath sounds. Report changes immediately.

Frequently monitor blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine, potassium, sodium, chloride, and magnesium levels.

Provide continuous cardiac monitoring during acute and advanced stages to identify and treat arrhythmias promptly.

To prevent deep vein thrombosis from vascular congestion, help the patient with range-of-motion exercises. Apply antiembolism stockings as needed. Check for calf pain and tenderness.

Teaching about heart failure

Teaching about heart failure

Advise the patient to avoid foods high in sodium, such as canned or commercially prepared foods and dairy products, to curb fluid overload.

Stress the importance of taking digoxin (Lanoxin) exactly as prescribed. Tell the patient to watch for and immediately report signs of toxicity, such as anorexia, vomiting, and yellow vision.

Explain fluid restrictions.

Encourage the patient to participate in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation.

Stress the need for regular checkups.

Tell the patient to notify the practitioner promptly if his pulse rate is unusually irregular or measures less than 60 beats/minute; if he experiences dizziness, blurred vision, shortness of breath, a persistent dry cough, palpitations, increased fatigue, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, swollen ankles, or decreased urine output; or if he notices a rapid weight gain (3 to 5 lb [1.5 to 2.5 kg) in 1 week.

Discuss the importance of smoking cessation.

Classifying signs and symptoms to determine treatment

Two sets of guidelines are available to help direct treatment of patients with heart failure. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification is based on functional capacity. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines are based on objective assessment. These guidelines are compared below.

| NYHA classification | ACC/AHA guidelines | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Stage A: Patient is at high risk for developing heart failure but has no structural heart disease or signs and symptoms of heart failure. |

| |

| Class I: Ordinary physical activity doesn’t cause undue fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, or angina. | Stage B: Patient has structural heart disease but no signs and symptoms of heart failure. |

|

| Class II: Patient has slight limitation of physical activity but is asymptomatic at rest. Ordinary physical activity causes fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, or anginal pain. Class III: Patient has marked limitation of physical activity but is typically asymptomatic at rest. Less than ordinary physical activity causes fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, or angina. | Stage C: Patient has structural heart disease with prior or current signs and symptoms of heart failure. |

|

| Class IV: Patient is unable to perform any physical activity without discomfort; symptoms may be present at rest. Discomfort increases with physical activity. | Stage D: Patient has end-stage disease requiring specialized treatment strategies, such as mechanical circulatory support, continuous inotropic infusion, or heart transplantation. |

|

Hypertension

Hypertension is an intermittent or sustained elevation in diastolic or systolic blood pressure. It may occur as essential (primary, idiopathic) where there is no identifiable cause, or secondary, resulting from an identifiable cause. Primary hypertension occurs in 90% to 95% of cases and tends to develop gradually over many years. Risk factors include obesity, stress, sedentary lifestyle, and smoking. Secondary hypertension tends to appear suddenly and causes higher blood pressure than does primary. Various conditions can lead to secondary hypertension, including renal disease, adrenal gland tumors, congenital coarctation, and obstructive sleep apnea. Medications that can cause secondary hypertension include hormonal contraceptives, cold remedies, certain pain relievers, and illegal drugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines. Malignant hypertension is a severe, fulminant form of hypertension common to both types. Hypertension is a major cause of stroke, cardiac disease, and renal failure. The prognosis is good if this disorder is detected early and treatment begins before complications develop. Severely elevated blood pressure (hypertensive crisis) may be fatal.

Signs and symptoms

Possibly none

Blurry vision

Bruits over abdominal aorta or carotid, renal, and femoral arteries

Confusion

Dizziness or light-headedness

Edema

Elevated blood pressure from baseline

Fatigue

Nocturia

Nose bleeds

Classification of blood pressure

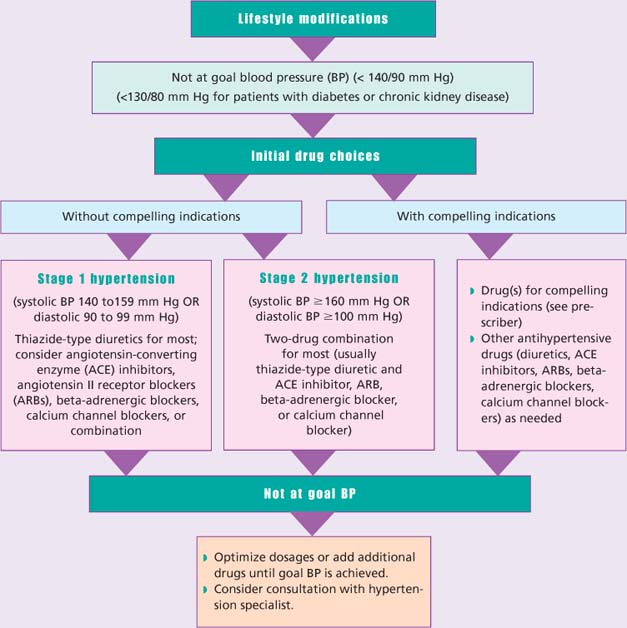

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommends that a person’s risk factors be considered in the treatment of his hypertension. The patient with more risk factors should be treated more aggressively.

| Category | SBP mm Hg | DBP mm Hg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 120 | and | < 80 |

| Prehypertension | 120 to 139 | or | 80 to 89 |

| Hypertension, stage 1 | 140 to 159 | or | 90 to 99 |

| Hypertension, stage 2 | ≥ 160 | or | ≥ 100 |

| Key: SBP = systolic blood pressure DBP = diastolic blood pressure | |||

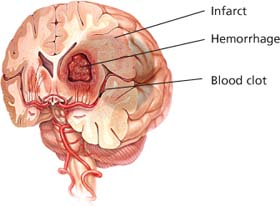

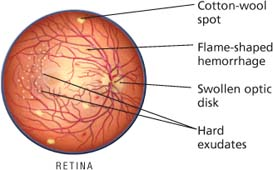

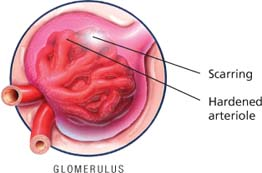

The silent killer

Although patients may feel healthy, untreated or poorly controlled hypertension can damage their major organs. Organs at greatest risk are the brain, eyes, and kidneys.

Brain

Eye

Nursing considerations

If a patient is hospitalized with hypertension, find out if he was taking his prescribed medications. If he wasn’t, investigate the reasons. Refer him to the appropriate social service department for needed assistance, if appropriate.

When routine blood pressure screening reveals elevated pressure, make sure the sphygmomanometer cuff size is appropriate for the patient’s upper arm circumference. Take the pressure in both arms in lying, sitting, and standing positions. Ask the patient if he smoked, drank a beverage containing caffeine, or was emotionally upset before the reading. Advise him to return for blood pressure testing at frequent and regular intervals.

To help identify hypertension and prevent untreated hypertension, participate in public education programs dealing with hypertension and ways to reduce risk factors. Encourage public participation in blood pressure screening programs. Routinely screen all patients, especially those at risk (blacks and those with family histories of hypertension, stroke, or heart attack).

Teaching about hypertension

Teaching about hypertension

Teach the patient to use a self-monitoring blood pressure cuff and to record the reading at least twice weekly in a journal for review by the physician at every office appointment.

Tell the patient and family to keep a record of drugs used in the past, noting especially which ones are or aren’t effective.

To encourage compliance with antihypertensive therapy, suggest establishing a daily routine for taking medication. Tell him to report any adverse reactions to prescribed drugs. Advise him to avoid high-sodium antacids and over-the-counter cold and sinus medications containing harmful vasoconstrictors.

Help the patient examine and modify his lifestyle. Suggest stres-reduction groups, dietary changes, and an exercise program, particularly aerobic walking, to improve cardiac status and reduce obesity and serum cholesterol levels.

Encourage a change in dietary habits. Help the obese patient plan a reducing diet. Tell him to avoid high-sodium foods (such as pickles, potato chips, canned soups, and cold cuts), table salt, and foods high in cholesterol and saturated fat.

Teach the patient and his family that this is a lifelong treatment. Warn the patient and family about complications that may occur from noncompliance and uncontrolled blood pressure, such as stroke and heart attack.

ACS tissue destruction

ACS tissue destruction

Determining types of aortic aneurysms

Determining types of aortic aneurysms

Understanding cardiac tamponade

Understanding cardiac tamponade

Looking at dilated cardiomyopathy

Looking at dilated cardiomyopathy

Looking at restrictive cardiomyopathy

Looking at restrictive cardiomyopathy

Libman-Sacks endocarditis

Libman-Sacks endocarditis

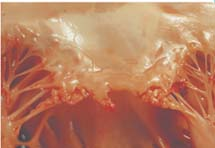

Bacterial endocarditis

Bacterial endocarditis

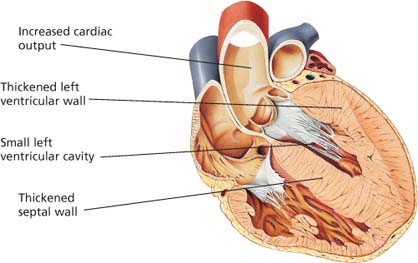

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Left ventricular hypertrophy