C

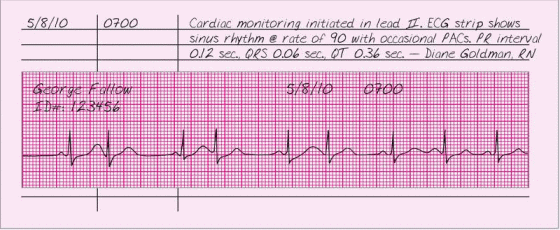

CARDIAC MONITORING

Because it allows continuous observation of the heart’s electrical activity, cardiac monitoring is useful not only for assessing cardiac rhythm, but also for gauging a patient’s response to drug therapy and for preventing complications associated with diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Like other forms of electrocardiography, cardiac monitoring uses electrodes placed on the patient’s chest to transmit electrical signals that are converted into a tracing of cardiac rhythm on an oscilloscope. Cardiac monitoring may be hardwire monitoring, in which the patient is connected to a monitor at bedside, or telemetry, in which a small transmitter connected to the patient sends an electrical signal to a monitor screen for display.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

In your note, document the date and time that monitoring began and the monitoring leads used. Attach all rhythm strip readings to the record. Be sure to label the rhythm strip with the patient’s name, his room number, and the date and time if the monitor doesn’t do this automatically. Measure and document the PR interval, QRS duration, and QT interval along with an interpretation of the rhythm. Also, document any changes in the patient’s condition, and place a rhythm strip in the chart.

If cardiac monitoring will continue after the patient’s discharge, document which caregivers can interpret dangerous rhythms and can perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Also, teach troubleshooting techniques to use if the monitor malfunctions, and document your teaching efforts or referrals (for example, to equipment suppliers).

|

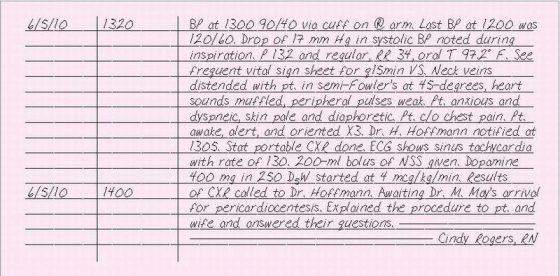

CARDIAC TAMPONADE

Within cardiac tamponade, a rapid, unchecked rise in intrapericardial pressure impairs diastolic filling of the heart. The rise in pressure usually results from blood or fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac. If fluid accumulates rapidly, the patient requires emergency lifesaving measures.

Cardiac tamponade may be idiopathic (Dressler’s syndrome) or may result from effusion, hemorrhage from trauma or nontraumatic causes, pericarditis, acute myocardial infarction, chronic renal failure during dialysis, drug reaction, or connective tissue disorders.

If you suspect cardiac tamponade in your patient, notify the doctor immediately and prepare for pericardiocentesis (needle aspiration of the pericardial cavity), emergency surgery (usually a pericardial window), or both. Anticipate I.V. fluids, inotropic drugs, and blood products to maintain blood pressure until treatment is performed.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Note the date and time that you detect signs of tamponade. Include your assessment findings, such as neck vein distention, decreased arterial blood pressure, pulsus paradoxus, narrow pulse pressure, muffled heart sounds, acute chest pain, dyspnea, diaphoresis, anxiety, restlessness, pallor or cyanosis, rapid and weak pulses, and hepatomegaly. Record the name of the doctor notified and the time of notification. Make a note of diagnostic tests ordered by the doctor, such as an ECG or chest X-ray, and the findings. Document treatments and procedures and the patient’s response. Note any patient teaching provided. Frequency of vital signs and titration of drugs and patient responses may be documented on the appropriate flow sheets.

|

CARDIOPULMONARY ARREST AND RESUSCITATION

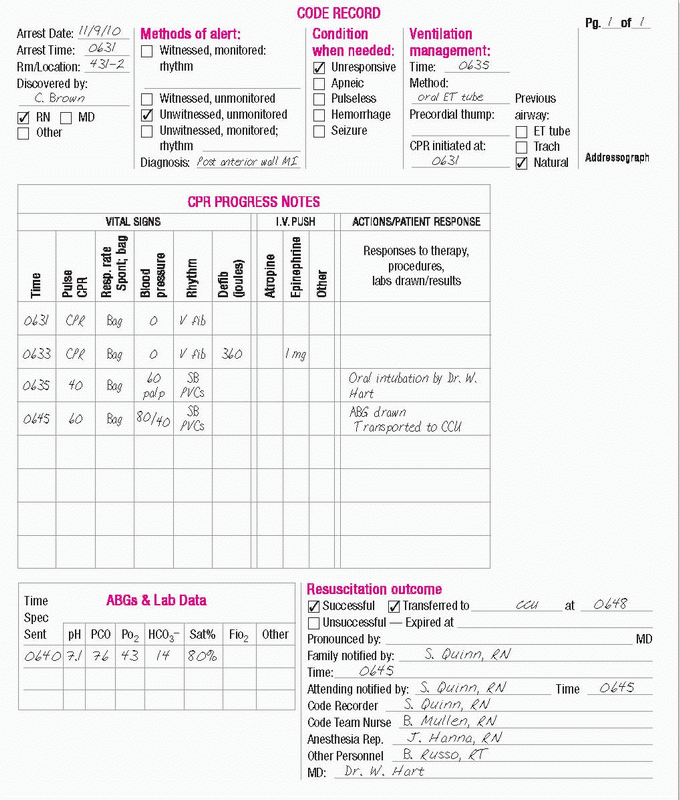

Guidelines established by the American Heart Association direct you to keep a written, chronological account of a patient’s condition throughout cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). If you’re the designated recorder, document therapeutic interventions and the patient’s responses as they occur. Don’t rely on your memory later. Writing “recorder” after your name indicates that you documented the event but didn’t participate in the code.

The form used to chart a code is the code record. It incorporates detailed information about your observations and interventions as well as drugs given to the patient. Remember, the code response should follow Advanced Cardiac Life Support guidelines.

Some facilities use a resuscitation critique form to identify actual or potential problems with the resuscitation process. This form tracks personnel responses and response times as well as the availability of appropriate drugs and functioning equipment.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

The code record is a precise, quick, and chronological recording of the events of the code. (See The code record, page 54.) Document the date and time the code was called. You’ll also need to record the patient’s name, location of the code, person who discovered the patient, the patient’s condition, and whether the arrest was witnessed or unwitnessed. Document the name of the doctor running the code, and list other members who participated in the code. Record the exact time for each code intervention, and include vital signs, heart rhythm, laboratory results (such as arterial blood gas or electrolyte levels), type of treatment (such as CPR, defibrillation, or cardioversion), drugs (name, dosage, and route), procedures (such as intubation, temporary or transvenous pacemaker, and cen tral line insertion), and patient response. Record the time that the family was notified. At the end of the code, indicate the patient’s status and the time that the code ended. Some facilities require that the doctor leading the code and the nurse recording the code review the code sheet and sign it.

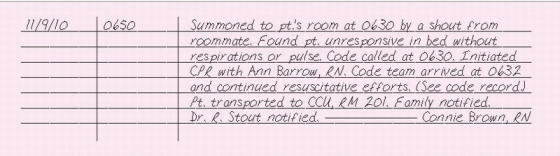

In your nurse’s note, record the events leading up to the code, your assessment findings prompting you to call a code, who initiated CPR, and other interventions performed before the code team arrived. Include the patient’s response to interventions. Indicate in your note that a code sheet was used to document the events of the code. Document notification of the family and attending physician.

|

CARDIOVERSION, SYNCHRONIZED

Used to treat tachyarrhythmias, cardioversion delivers an electric charge to the myocardium at the peak of the R wave. This causes immediate depolarization, interrupting reentry circuits and allowing the sinoatrial node to resume control. Synchronizing the electric charge with the R wave ensures that the current won’t be delivered on the vulnerable T wave and thus disrupt repolarization.

Indications for cardioversion include stable paroxysmal atrial tachycardia, unstable paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and ventricular tachycardia. Cardioversion may be an elective or urgent procedure, depending on how well the patient tolerates the arrhythmia.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

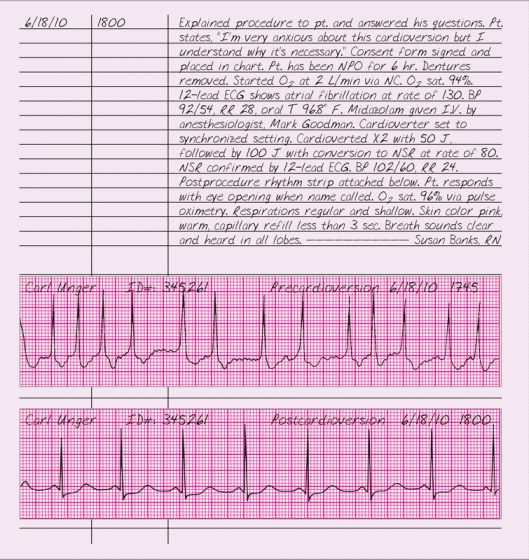

Document the date and time of the cardioversion. Record the signing of a consent form and any patient teaching. Include any preprocedure activities, such as withholding food and fluids, withholding drugs, removing dentures, administering a sedative, and obtaining a 12-lead ECG. Document vital signs, and obtain a rhythm strip before starting. Note that the cardioverter was on the synchronized setting, how many times the patient was cardioverted, and the voltage used each time. After the procedure, obtain vital signs, place a rhythm strip in the chart, and record that a 12-lead ECG was obtained. Assess and document the patient’s level of consciousness, airway patency, respiratory rate and depth, and use of supplemental oxygen until he’s awake. Indicate the specific time of each assessment and avoid block charting.

|

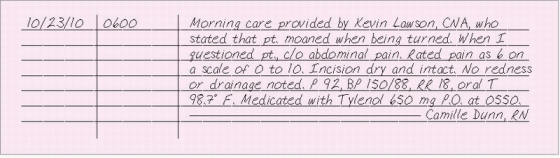

CARE GIVEN BY SOMEONE ELSE

Unless you document otherwise, anyone reading your notes assumes that they’re a firsthand account of care provided. In some settings, nursing assistants and technicians aren’t allowed to make formal charting entries. If this is the case in your facility, determine what care was provided, assess the patient and the task performed (for example, a dressing change), and document your findings.

If your facility allows unlicensed personnel to chart, you may have to countersign their notes. If your facility’s policy states that the unlicensed person must provide care in your presence, don’t countersign unless you actually witness her actions. If the policy says you don’t have to be there, your countersignature indicates the note describes care that the other person had the authority and competence to perform and that you verified the procedure was performed. Unless your facility authorizes or requires you to witness someone else’s notes, your signature will make you responsible for anything put in the notes above it. So if another nurse asks you to document her care or sign her notes, tell her you refuse.

CAREGIVER STRAIN

Illness in a family member commonly takes a toll on other family members and caregivers. In fact, family members under great stress from trying to carry out their own roles while also caring for a sick person are at risk for burnout. If the patient has a long-term illness such as Alzheimer’s disease, the caregiver could be facing years of hard work. Signs of stress in a caregiver include muscular aches, headache, insomnia, illness, unexplained pain or GI complaints, fatigue, weight loss, grinding teeth, inability to concentrate, mood swings, use of tranquilizers or alcohol, decreased socialization, depression, forgetfulness, feelings of despair, and thoughts of suicide.

Refer caregivers at risk for or showing signs of strain to social services. Educate caregivers about signs and symptoms of stress to report to their doctor or nurse. Help them identify support systems and tell them about community services that are available.

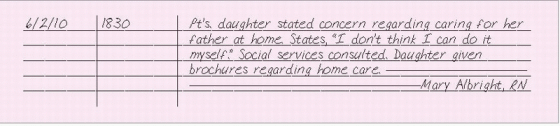

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of your entry. Identify the individual at risk for or experiencing caregiver strain. Describe subjective and objective signs of caregiver strain. Use the caregiver’s own words in quotes, when possible. Include education and support given and the caregiver’s response. Identify referrals made to services, such as social services, chaplain, support groups, Meals on Wheels, and respite care.

Family education may be documented on a patient education flow sheet, depending on facility policy. Appropriate notes should also be recorded on discharge planning forms.

|

CARE PLAN, STANDARDIZED

The standardized care plan is written to address patient outcomes, nursing actions, and broad interventions that are common to patients with a particular need or problem and are part of the patient’s medical record. The standardized care plan is used to save documentation time and improve the quality of care. The nurse may use a standardized care plan as an initial tool for planning care for patients. However, it must be developed and personalized based on the unique needs of the patient. Standardized care plans may be written with general outcomes and interventions or with spaces left blank so that individualized patient outcomes and interventions can be incorporated. Such care plans are commonly published in nursing care plan textbooks.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

The standardized care plan should include:

related factors and signs and symptoms for a nursing diagnosis. For instance, the form will provide a root diagnosis such as “Pain related to …” You might fill in “incisional pain as exhibited by grimacing and moaning with movement.”

time limits for the outcomes. To a root outcome statement of “Patient will perform postural drainage without assistance,” you might add “for 15 minutes immediately during daily morning care.” The expected outcome should also be realistic, achievable, measurable, observable, behavioral, patient centered, and mutually agreed upon.

frequency of interventions. You can complete an intervention such as “Perform passive range-of-motion exercises” with “twice per day: 1 × each in the morning and evening.”

specific instructions for interventions. For a standard intervention such as “Elevate patient’s head of bed,” you might specify “Before sleep, elevate the patient’s head on three pillows.”

Refer to Using a standardized care plan, page 60 for sample documentation.

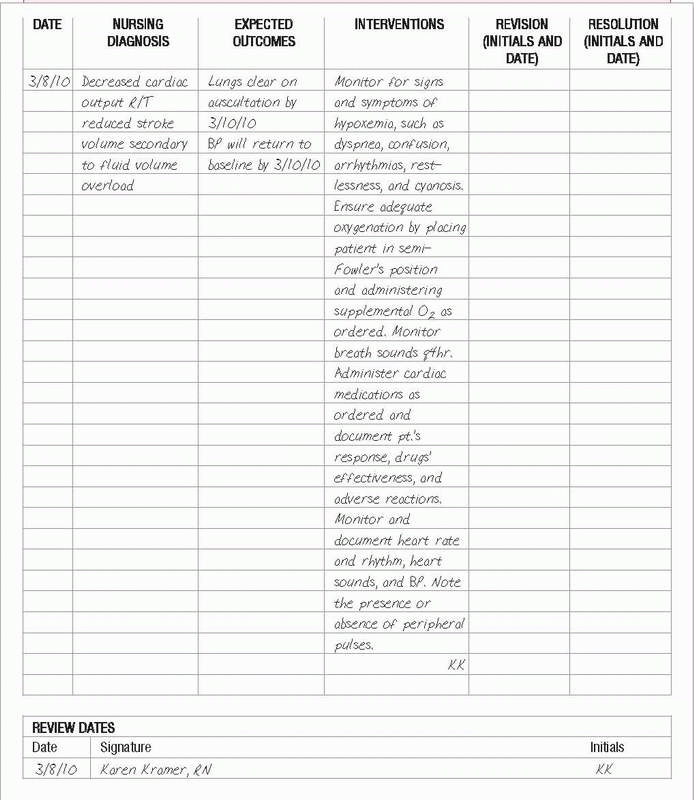

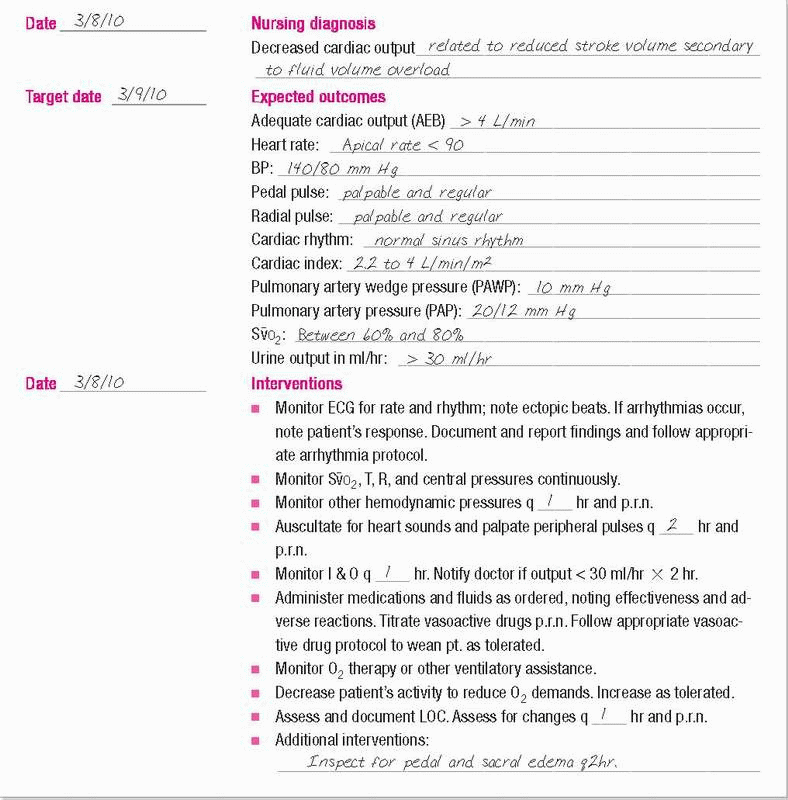

USING A STANDARDIZED CARE PLAN

USING A STANDARDIZED CARE PLANThe standardized care plan below is for a patient with a nursing diagnosis of Decreased cardiac out-put. To customize it to your patient, you would complete the diagnosis—including related factors and signs and symptoms—and fill in the expectedoutcomes. You would also modify, add, or delete interventions as necessary.

|

CARE PLAN, TRADITIONAL

The nursing care plan serves as a written guide to facilitate continuity of care for individual patients. The care plan provides an avenue for communication among health care providers who interact to deliver comprehensive care.

The traditional care plan is initiated when the patient is admitted and continues throughout the hospitalization. The patient’s problem, expected outcomes, specific interventions, and evaluations, along with the date that the problem was resolved, are typical components of the traditional care plan. The traditional care plan is written from scratch and is rarely used today because of the time required to write one for each patient. It is, however, specific to the patient so that all health care workers understand the precise patient problem, expected outcomes, and individualized interventions.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

The traditional care plan includes dates for problem identification and resolution, the problem (written as a nursing diagnosis), the expected patient outcomes, individualized nursing interventions, and evaluation of the expected outcome. (See Using a traditional care plan, page 62.)

CAST CARE

A cast is a hard mold that encloses a body part, usually an extremity, to provide immobilization without discomfort. It can be used to treat injuries, correct orthopedic conditions, or promote healing after general or plastic surgery, amputation, or neurovascular repair. Care of the cast involves assessment of the limb for neurovascular function, prevention of complications, and patient and family education. Complications include compartment syndrome, palsy, paresthesia, ischemia, ischemic myosis, pressure necrosis, and misalignment or nonunion of fractured bones.

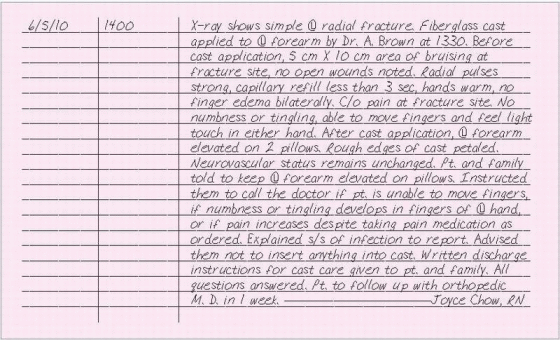

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of, and the reason for, cast application and skin condition of the extremity before the cast was applied. Document diagnostic tests performed and the results. Note any contusions, redness, or open wounds. Assess and document the results of neurovascular checks, before and after application, bilaterally. Include the location of special devices, such as felt pads or plaster splints. Document patient education and whether written instructions were given. Patient education may be documented in emergency department (ED) notes, nurse’s notes, patient education forms, or discharge sections of the chart.

|

CENTRAL VENOUS ACCESS DEVICE INSERTION

A central venous access device (CVAD) is a sterile catheter that’s inserted through a major vein, such as the subclavian vein, jugular vein, or femoral vein. CVAD therapy allows CV pressure monitoring, which indicates blood volume or pump efficiency. It also permits aspiration of blood samples for diagnostic tests and administration of I.V. fluids (in large amounts, if necessary) in emergencies or when decreased peripheral circulation causes peripheral veins to collapse. A CVAD helps when prolonged I.V. therapy reduces the number of accessible peripheral veins, when solutions must be diluted (for large volumes or for irritating or hypertonic fluids such as total parenteral nutrition solutions), and when long-term access is needed to the patient’s venous system. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is inserted in a peripheral vein, such as the basilic vein, and used for infusion and blood sampling only.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

When you assist the doctor who inserts a CVAD, document the time and date of insertion; type, length, and location of the catheter; solution infused; the doctor’s name; and the patient’s response to the procedure. If the ports aren’t being used, document that they have needle-free injection caps and include any orders related to maintaining patency. You’ll also need to document the time and results of the X-ray performed to confirm placement. Note whether the catheter is sutured in place and the type of dressing applied. For a PICC, record the length of the external catheter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

THE CODE RECORD

THE CODE RECORD

USING A TRADITIONAL CARE PLAN

USING A TRADITIONAL CARE PLAN