Aromatherapy

Linda L. Halcón

Aromatherapy is a relatively recent addition to nursing care in the United States, although it is growing in popularity within health care settings worldwide. Aromatherapy is offered by nurses in many countries, including Switzerland, Germany, Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, and the United Kingdom, and it has been a medical specialty in France for many years. This modality is particularly well suited to nursing, because it incorporates the therapeutic value of sensory experience (i.e., smell) and often includes the use of touch in the delivery of care. It also builds on a rich heritage of botanical therapies within nursing practice (Libster, 2002, 2012).

Aromatherapy has been part of herbal or botanical medicine for millenia. There is evidence of plant distillation and the use of essential oils and other aromatic plant products dating back 5,000 years. In ancient Egypt and the Middle East, plant oils were used in embalming, incense, perfumery, and healing. Therapeutic applications of essential oils were recorded as part of Greek and Roman medicine, and essential oils have been used in Ayurvedic medicine and in traditional Chinese medicine for more than 1,000 years. With the expansion of trade and improvements in distillation methods, essential oils became common elements of herbal medicine and perfumery in Europe during the Middle Ages (Keville & Green, 2009). In the late 1800s, scientists noted the association between environmental exposure to plant essential oils and the prevention of disease, and microbiologists conducted studies showing the in vitro activity of certain plant oils against microorganisms (Battaglia, 2003). More recent studies confirm the antimicrobial properties of essential oils (Solorzano-Santos & Miranda-Novales, 2012).

The development of clinical aromatherapy within the context of modern Western health science began in France just prior to World War I, when chemist Maurice Gattefossé was healed of a near-gangrenous wound with lavender essential oil. He subsequently championed its use for infections and battle wounds. Physician Jean Valnet and nurse Marguerite Maury followed Gattefossé in promoting the therapeutic value of essential oils in Europe, and, in the 1930s, interest in the anti-infective value of essential oils began to appear in the European and Australian medical literature (Price & Price, 2011). The use of essential oils continued sporadically as a nonconventional treatment modality in the West until the recent explosion of interest in botanical medicines, when its use became more visible and widespread. In their groundbreaking survey research on the use of complementary and alternative therapies in the United States, Eisenberg et al. (1998) reported that 5.6% of 2,055 adults surveyed used aromatherapy. More recent large surveys estimating the overall prevalence of complementary therapies have not included aromatherapy as a separate modality (Barnes, Bloom, & Nahin, 2008; Tindle, Davis, Phillips, & Eisenberg, 2005). Surveys of special populations, however, suggest its continuing and increasing use by the public (Crawford, Cincotta, Lim, & Powell, 2006; Sinha & Efron, 2005).

DEFINITION

There are many operant definitions of aromatherapy, and some of them contribute to common misconceptions. The word aromatherapy can lead people to believe that it simply involves smelling scents but this is incorrect. It is important to remember that the widespread use of synthetic scents in household and personal products is not considered aromatherapy. Styles (1997) defined aromatherapy as the use of essential oils for therapeutic purposes that encompass mind, body, and spirit—a broad definition that is consistent with holistic nursing practice. The National Cancer Institute defines aromatherapy as the “therapeutic use of essential oils from flowers, herbs, and trees for the improvement of physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being” (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2012). Buckle defined clinical aromatherapy in nursing as the use of essential oils for expected and measurable health outcomes (Buckle, 2000). Because aromatherapy clinical research is still in its early developmental stages in the United States, the evidence base for using aromatherapy in nursing practice sometimes may be difficult to establish; however, there are findings for and against the use of a number of essential oils, and it is important to evaluate the available scientific data for aromatherapy practice.

Essential oils are obtained from a variety of plants worldwide, but not all plants produce essential oils. For those that do, the essential oils may be found in the plants’ flowers, leaves, stems, bark, roots, seeds, resin, or

peels. Most essential oils are obtained by steam distillation of a specific plant material. Steam-distilled essential oils are concentrated substances made up of the oil-soluble, lower-molecular-weight chemical constituents found in the source-plant material. Essential oils from citrus fruit peels are usually obtained by expression (similar to grating or grinding). Carbon dioxide extraction is increasingly accepted by scientists and practitioners as an acceptable method for obtaining essential oils; however, other types of solvent extraction generally are not preferred for clinical use. Expressed and CO2 extracted essential oils contain a broader range of the chemicals present in the plant material; thus, they may have different therapeutic properties. Essential oils do not necessarily have the same medicinal properties as the plants from which they are derived because they do not contain the whole spectrum of chemicals present in the whole plant.

peels. Most essential oils are obtained by steam distillation of a specific plant material. Steam-distilled essential oils are concentrated substances made up of the oil-soluble, lower-molecular-weight chemical constituents found in the source-plant material. Essential oils from citrus fruit peels are usually obtained by expression (similar to grating or grinding). Carbon dioxide extraction is increasingly accepted by scientists and practitioners as an acceptable method for obtaining essential oils; however, other types of solvent extraction generally are not preferred for clinical use. Expressed and CO2 extracted essential oils contain a broader range of the chemicals present in the plant material; thus, they may have different therapeutic properties. Essential oils do not necessarily have the same medicinal properties as the plants from which they are derived because they do not contain the whole spectrum of chemicals present in the whole plant.

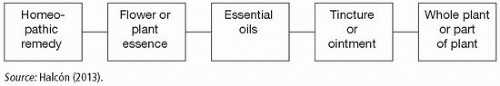

Nurses have an important role in helping patients to differentiate among the range of botanical products that are easily available. Misunderstanding the origin and makeup of these products can result in unnecessary risk. The most commonly used botanical products can be viewed as a continuum (Exhibit 20.1). On one end of the continuum are whole herbs, referring to unprocessed material from whole plants or parts of plants (Exhibit 20.1, far-right box). This is the oldest and most common form of botanical medicines worldwide. Tinctures and ointments are different from the whole plant and are also different from essential oils (Exhibit 20.1, second box from right). They are often confused with each other, and it is important that nurses understand the difference in order to provide advice on their relative safety. Tinctures contain chemicals obtained from the plant material using alcohol as a solvent, and they include both water-soluble and oil-soluble chemicals. Tinctures are often taken orally or sublingually, with the dose and timing depending on the practitioner and the purpose. They are not as concentrated as essential oils. Ointments are made using vegetable oil (e.g., olive oil) rather than alcohol as the solvent. Plant-based tinctures and ointments are widely available. Flower essences (Exhibit 20.1, second box from left) are also often confused with essential oils. Essences contain little if any of the original plant material, but they are thought to contain the vibrations or frequencies of the plants they are made from. It is the frequency that is considered the source of their therapeutic action, not the physical chemistry. Homeopathy (Exhibit 20.1, far-left box) was developed in Europe and was very popular in the United States in the late 1800s and early

1900s (Dooley, 2002). It declined in popularity as biomedicine became the dominant paradigm. Homeopathic remedies contain no molecules of the materials from which they are made. They are thought to work subtly on a vibrational level to promote balance and healing. Homeopathic remedies may be prescribed by a homeopathic physician or may be obtained over the counter. Homeopathy is becoming more popular in the United States once again; thus, nurses may benefit from understanding its basic concepts and differentiating it from other natural products.

1900s (Dooley, 2002). It declined in popularity as biomedicine became the dominant paradigm. Homeopathic remedies contain no molecules of the materials from which they are made. They are thought to work subtly on a vibrational level to promote balance and healing. Homeopathic remedies may be prescribed by a homeopathic physician or may be obtained over the counter. Homeopathy is becoming more popular in the United States once again; thus, nurses may benefit from understanding its basic concepts and differentiating it from other natural products.

SCIENTIFIC BASIS

Essential oils processed by any of the above methods are highly volatile, complex mixtures of organic chemicals consisting of terpenes and terpenic compounds. The chemistry of an essential oil largely determines its therapeutic properties. There are 60 to 300 separate chemicals in each essential oil, and the proportions of the constituents for a particular plant species vary depending on a host of genetic and environmental factors. Knowing the plant species, the chemotype, the part of the plant used, the country of origin, and the method of extraction can provide an indication of an essential oil’s chemical constituents using readily available aromatherapy textbooks.

The pharmacological activity of essential oils begins on entry into the body through the olfactory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or integumentary systems. All body systems can be affected once the chemical molecules making up essential oils reach the circulatory and nervous systems. A proportion of the compounds within an essential oil finds its way into the body, however applied (Tisserand & Balacs, 1995), although the degree and rate of absorption vary depending on the route of administration. Inhaled aromas have the fastest effect, although compounds have been detected in the blood following massage (Cross, Russell, Southwell, & Roberts, 2008).

When inhaled, the many different molecules in each essential oil act as olfactory stimulants that travel via the nose to the olfactory bulb, and from there impulses travel to the brain. The amygdala and the hippocampus are of particular importance in the processing of aromas. The amygdala governs emotional responses. The hippocampus is involved in the formation and retrieval of explicit memories. The limbic system interacts with the cerebral cortex, contributing to the relationship between thoughts and feelings; it is directly connected to those parts of the brain that control heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, stress levels, and hormone levels (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2008). Although inhalation of essential oils is largely thought to affect the mind and body through the process of olfaction, some molecules from any inhaled vapor travel to the lungs, where they can have an effect on breathing and may be absorbed into the circulatory system. Tisserand and Balacs (1995) gave the example of the effect of Lavandula angustifolia (true lavender), thought to reduce the

effect of external emotional stimuli by increasing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which in turn inhibits neurons in the amygdala, producing a sedative effect similar to that of diazepam (Tisserand, 1988). More recent work supports physiological bases for the neurological actions of essential oils (Bagetta et al., 2010; Komiya, Takeuchi, & Harada, 2006).

effect of external emotional stimuli by increasing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which in turn inhibits neurons in the amygdala, producing a sedative effect similar to that of diazepam (Tisserand, 1988). More recent work supports physiological bases for the neurological actions of essential oils (Bagetta et al., 2010; Komiya, Takeuchi, & Harada, 2006).

It is estimated that, at most, about 10% of an essential oil may be absorbed through the skin upon topical application (Cross et al., 2008; Tisserand, 2010), and there is controversy about skin penetration among essential oil researchers. Essential oils seem to be absorbed through the skin by diffusion, with the epidermis and fat layer acting as a reservoir before the components of the essential oils reach the dermis and the bloodstream. In some instances, topically applied essential oil preparations were used to enhance the dermal penetration of pharmaceuticals (Nielsen, 2006; Williams & Barry, 1989). There is some debate among essential oil experts about the rate and extent of penetration and absorption; however, there is evidence that penetration can vary depending on the condition of the skin, the age of the patient, and the carrier or vehicle for the essential oil. In addition, massage can enhance dermal penetration through heat and friction, and occlusion can enhance penetration. Essential oils are excreted from the body through the kidneys, respiration, and insensate loss.

INTERVENTION

The choice of application method depends on the condition being treated or the desired effect, the nurse’s knowledge and practice parameters, the available or desired time for the action to occur, the targeted outcome, the chemical components of the essential oil, and the preferences and psychological needs of the patient.

Although essential oils are not always pleasant smelling, inhalation is one of the simplest and most direct application procedures. With this method, 1 drop to 5 drops of an essential oil can be placed on a tissue or floated on hot water in a bowl and then inhaled for 5 minutes to 10 minutes. Other inhalation techniques include the use of diffusers, burners, nebulizers, and vaporizers that can be operated by heat, battery, or electricity and may or may not include the use of water. Larger, portable aroma-inhalation systems are available commercially to provide controlled release of essential oils into rooms of any size.

Inhalation effects as well as skin effects are experienced when essential oils are used in a bath. Baths have been found especially helpful to promote relaxation and sleep in care settings and in the home. Lavender (L. angustifolia) is the essential oil most commonly used for these purposes, not only because it promotes relaxation but also because it is generally well tolerated on the skin. For bath-use techniques, see Exhibit 20.2.

Exhibit 20.2. Therapeutic Bath with Essential Oils

Four drops to six drops of the essential oil may be dissolved first in a teaspoon of whole milk, rubbing alcohol, or carrier oil (cold-pressed) and then placed in the bath water. Because essential oils are not soluble in water, they would float on the top of the water if they were used without a dispersant, and this could result in an uneven and possibly too concentrated treatment. An essential-oil bath should last about 10 minutes to 15 minutes. Essential oils also may be dissolved in salts (e.g., Epsom salts), which may be soothing to muscles and joints. One such recipe for bath salts consists of 1 tablespoon of baking soda, 2 tablespoons of Epsom salts, and 3 tablespoons of sea salt with 4 drops to 6 drops of essential oils mixed throughout. Salts should be added to the bath water just before immersion and after agitating the water to disperse them.

Compresses can be a useful method for applying essential oils to treat skin conditions or minor injuries. To prepare a compress, add 4 drops to 6 drops of essential oil to warm water. Soak a soft cotton cloth in the mixture, wring it out, and apply the cloth to the affected area, contusion, or abrasion. Cover the compress with plastic wrap to retain moisture, place a towel over the plastic wrap, and keep it in place for as long as desired (up to 4 hours). The use of very warm water can enhance the absorption of some of the components of essential oils (Buckle, 2003).

Massage also can facilitate absorption of essential oils through the skin and can reduce the patient’s perceived stress, thus enhancing the healing process and possibly communication as well. To create a mixture for massage, dilute 1 drop to 2 drops of an essential oil in a teaspoon (5 mL) of cold-pressed vegetable oil, organic and scent-free cream, or gel. Mixtures for massage are generally 1% to 5% essential oil concentration (Tisserand & Balacs, 1995), using very low concentrations when massaging large areas of the body.

Essential oils should not be used undiluted on mucous membranes; even on intact skin they are generally used in concentrations seldom exceeding 10%. When used to treat conditions such as vaginal infections, essential-oil preparations can be created or purchased as pessaries or suppositories. Only essential oils high in alcohols, such as tea tree, are appropriate in pessaries; alcohols are less likely to cause skin irritation. If essential oils are applied via tampons, they should be changed regularly (Buckle, 2003). Oral thrush (candidiasis) in adults also can be treated with diluted essential oils by the swish-and-spit method, taking care not to swallow (Jandourek, Vaishampayan, & Vazquez, 1998). Recent studies suggest that essential oils in a mouthwash solution

can help prevent dental caries and treat periodontal disease (Bagg, Jackson, Sweeney, Ramage, & Davies, 2006; Carvalhinho, Costa, Coelho, Martins, & Sampaio, 2012).

can help prevent dental caries and treat periodontal disease (Bagg, Jackson, Sweeney, Ramage, & Davies, 2006; Carvalhinho, Costa, Coelho, Martins, & Sampaio, 2012).

General Guidelines for Use of Essential Oils

Nurses should be aware of general safety guidelines for patient education and in practice. These include:

Store essential oils away from open flames; they are volatile and highly flammable.

Store essential oils in a cool place away from sunlight; use amber- or dark blue-colored glass containers. Close the container immediately after use. Essential oils can oxidize in the presence of heat, light, and oxygen, changing their chemistry and thus their actions in unpredictable ways.

Be aware that essential oils can stain clothing and textiles and that undiluted essential oils can degrade some plastics. Take appropriate precautions.

Keep essential oils away from children and pets unless you are wellversed in clinical aromatherapy. The literature contains cases of adverse reactions or deaths related to improper applications or accidental ingestion in young children and pets (Halicioglu, Astarcioglu, Yaprak, & Aydinlioglu, 2011).

Use essential oils from reputable suppliers. Seek the advice of a trained aromatherapist or the recommendation of a knowledgeable clinical provider. If using essential oils in clinical or research settings, test results verifying the chemical constituency should be obtained.

Special care is needed when using essential oils with or around persons who have a history of severe asthma or multiple allergies. Be sure to ask.

Despite the relative safety of essential oils when used properly, sensitization and skin irritation can occur with topical application. In these cases, any residual essential oil solution should be removed with oil or whole milk, rinsed with water, and its use should be discontinued. Most such reactions resolve without treatment; however, a health care provider should be consulted if discomfort/itching is severe or persists.

If an essential oil gets into the eyes, rinse it out with milk or carrier oil first and then with water.

Measurement of Outcomes

Selection of suitable methods to assess aromatherapy effects will depend on the problem for which essential oils are used and the targeted outcomes of treatment. For example, if lavender is used to promote sleep,

measures might include physiological markers, changes in sleep patterns, or comparison of signs and symptoms of insomnia between a treated group and another group that is similar in all ways other than the treatment. For psychological conditions such as depression or anxiety, many reliable survey instruments are available and they can be further validated by adding physiological measures such as cortisol levels or skin temperature. For infectious disease outcomes, standard laboratory tests can be used to measure the effect of treatment on microbial load. Other useful measures could include digital photography, pain scales, qualityof-life scales, tests of cognitive performance, or electroencephalogram results. Using established measurement tools where possible is helpful in facilitating interpretation and comparing the effects of essential oils with those of other approaches.

measures might include physiological markers, changes in sleep patterns, or comparison of signs and symptoms of insomnia between a treated group and another group that is similar in all ways other than the treatment. For psychological conditions such as depression or anxiety, many reliable survey instruments are available and they can be further validated by adding physiological measures such as cortisol levels or skin temperature. For infectious disease outcomes, standard laboratory tests can be used to measure the effect of treatment on microbial load. Other useful measures could include digital photography, pain scales, qualityof-life scales, tests of cognitive performance, or electroencephalogram results. Using established measurement tools where possible is helpful in facilitating interpretation and comparing the effects of essential oils with those of other approaches.

Precautions

Aromatherapy is a very safe complementary therapy if it is used with knowledge and within accepted guidelines. Many essential oils have been tested by the food and beverage industry for use as flavorings and preservatives, and much research has been carried out by the perfume and tobacco industries. Most of the essential oils commonly used in clinical aromatherapy have been given GRAS (generally regarded as safe) status. However, nurses should not administer essential oils orally, as this is outside a nurse’s scope of practice, and poisonings have been documented (Jacobs & Hornfeldt, 1994; Janes, Price, & Thomas, 2005). A list of contraindicated essential oils can be found in training manuals; both novices and more experienced practitioners should consult these lists. Most essential oils should not be used during early pregnancy and should be used cautiously in later pregnancy. Nurses need to be aware of essential oils that can cause photosensitivity, such as bergamot (Citrus bergamia) and other citrus oils (Clark & Wilkinson, 1998; Keljova, Jirova, Bendova, Gajdos, & Kolarova, 2010), and they should provide appropriate patient education and protection when these are used.

Essential oils are very concentrated and potent compounds, and in most cases they must be diluted in carrier oils for topical use. Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) and lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) are among the few exceptions to this rule. These essential oils can be used full strength on minor cuts, abrasions, and small burns.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access