Antigens, Antibodies, and Immunity

An antigen is any substance recognized as foreign by the immune system and therefore capable of producing an immune response. Antigens may be proteins, polysaccharides, polypeptides, nucleic acids, or substances such as pollen or bee and snake venom. Cells and tissues, including red blood cells, also contain antigens that the body recognizes as “self” or “non-self.” The major histocompatibility complex is a large cluster of genes located on chromosome 6, and it is the process by which the body codes its own antigens. Human leukocyte antigens are part of our individual genetic makeup, and the closer the human leukocyte antigen types are matched, the less chance of organ or tissue transplant rejection. If the immune system mistakes its own antigens as foreign, an autoimmune response results.

TERMS

If the immune system mistakes its own antigens as foreign, an autoimmune response results.

If the immune system mistakes its own antigens as foreign, an autoimmune response results.T cells and B cells are produced in the bone marrow and thymus gland. These cells interact with antigens as they circulate between body fluid and peripheral lymphoid tissue (e.g., tonsils, lymph nodes, spleen, intestinal lymphoid tissue) to either destroy the invading substance (T-cell function) or produce antibodies (B-cell function).

An antigen is any substance recognized as foreign by the immune system.

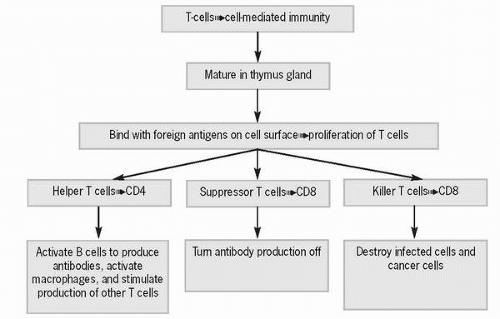

An antigen is any substance recognized as foreign by the immune system.T-Cell Function

There are two major types of T cells: regulator cells, including helper T cells and suppressor T cells, and effector cells, or killer T cells. The function of helper T cells is to activate B cells to produce antibodies, whereas the suppressor T cells turn the antibody production off. Cytotoxic T cells are capable of destroying cells infected with viruses by releasing lymphokines that destroy cell walls.

The closer the human leukocyte antigens types are matched, the less chance of organ or tissue transplant rejection.

The closer the human leukocyte antigens types are matched, the less chance of organ or tissue transplant rejection.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access