Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Joanne V. Hickey

The clinical and pathological findings of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were first described by Charcot in 1872.1 In more than 100 years since first described, ALS remains an uncommon and poorly understood disease in which patients progressively lose the ability to speak, swallow, and move their extremities.2 ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that involves both the upper and lower motor neurons. It is characterized by wasting of the muscles and progressive muscular paralysis as a result of destruction of motor neurons in the brainstem and the anterior gray horns of the spinal cord, along with degeneration of the pyramidal tracts. Some muscles become weak and atrophy, whereas spasticity and hyperreflexia are noted in others. “Amyotrophy” refers to the atrophy of the muscle fibers, which lead to weakness of the affected muscles and fasciculations. “Lateral sclerosis” refers to hardening of the anterior and lateral corticospinal tracts as motor neurons in these areas degenerate and is replaced by gliosis.3, 4

ALS is a progressive disease that leads to death most often from respiratory arrest. The cause of ALS has been elusive in spite of research efforts to understand the disease. ALS has been described as a complex genetic disorder in which multiple genetic and environmental factors combine to cause the disease. However, the contribution of any single factor is considered small.5 Most cases of ALS are sporadic with a small percentage familial. About two thirds of patients with typical ALS have a spinal form of the disease. The others have a limb form. Both will be discussed later in the chapter. Between 5% and 10% of cases are inherited as a Mendelian trait usually autosomal dominant, of which 15% to 20% are due to one of more than 100 mutations in the Cu—Zn superoxide dismutase type 1 gene (SOD1).6

In Western countries, the incidence of ALS is 2 per 1,00,000 people.7 Men are affected more frequently than women. The peak age of onset is 58 to 63 years for sporadic ALS and 47 to 52 years for familial disease.8 The overall median survival from onset of symptoms for ALS ranges between 2 and 3 years for bulbar onset and 3 and 5 years for limb onset.4, 9

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the development of ALS appear to be multifactorial with emerging evidence suggesting a complex interaction between genetics and molecular pathways. Research interest has focused on SOD1 and glutamate-induced excitotoxicity mediated motor neuron degeneration. No clear association between SOD1 mutations and premature death of motor neurons is evident although there is an association between genetic mutations and a toxic gain of function of the SOD1 enzyme with generation of free radicals which eventually lead to cell injury and death.8 The role of glutamates is also unclear. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. It binds N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid (AMPA) receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.10 Excessive activation of the postsynaptic receptors by glutamate can cause neurodegenerative changes through the activation of calcium-dependent enzymatic pathways.11 In addition, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity can cause neurodegeneration by damaging intracellular organelles and upregulating proinflammatory mediators.12 Research continues to examine other molecular pathways to untangle the evasive cause of ALS.

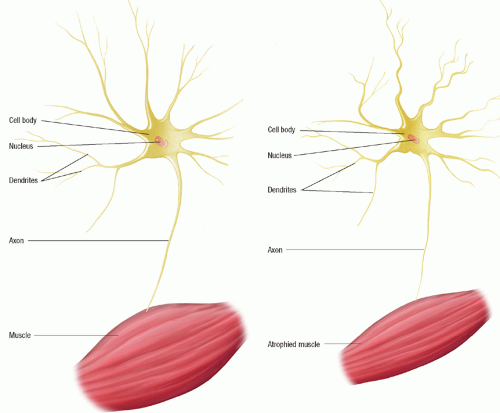

From a physiological perspective, there are marked degenerative changes in the following structures: anterior horn cells of the spinal cord; motor nuclei of the brainstem (especially nuclei of cranial nerves VII [facial] and XII [hypoglossal]); corticospinal tracts; and

Betz’s and precentral cells of the frontal cortex. Involvement of the upper motor neurons results in spasticity and reduced muscle strength whereas lower motor neuron involvement results in flaccidity, paralysis, and muscle atrophy (Fig. 34-1). The bowel and bladder are usually spared until very late in the disease. The sensory system is not affected.

Betz’s and precentral cells of the frontal cortex. Involvement of the upper motor neurons results in spasticity and reduced muscle strength whereas lower motor neuron involvement results in flaccidity, paralysis, and muscle atrophy (Fig. 34-1). The bowel and bladder are usually spared until very late in the disease. The sensory system is not affected.

Signs and Symptoms

Various patterns of involvement are possible, but the most common form of ALS presents with spinal symptoms (most common), bulbar symptoms, and limb symptoms. The development of symptoms in each category is briefly discussed. Silani et al.4 provide a clear picture of symptom development as follows. A discussion of cognitive and behavioral deficits is also included.

Spinal Symptoms

Patients may present with symptoms related to focal muscle weakness, which may start either distally or proximally in the upper or lower limbs. Muscle wasting rarely occurs before the onset of weakness. Patients may notice fasciculations (involuntary muscle twitching) or cramps preceding the onset of weakness or wasting for some months or even years. The weakness is insidious in onset, and is usually asymmetrical with the contralateral limbs developing weakness and wasting sooner or later. Most patients go on to develop bulbar and eventually respiratory symptoms. Gradually, spasticity may develop in the weakened atrophic limbs affecting manual dexterity and/or gait. Other occasionally encountered symptoms include bladder dysfunction (e.g., urgency), sensory symptoms, dementia, and parkinsonism.

Bulbar Symptoms

Bulbar palsy refers to a condition in which the dominant symptoms relate to weakness of the muscles innervated by the motor nuclei of the lower brainstem (i.e., muscles of the jaw, face, tongue, pharynx, and larynx) thus providing evidence of difficulty with articulation.1 The cranial nerves involved are IX, X, XI, and XII, which occur due

to a lower motor neuron lesion either at the nuclear or fascicular level in the medulla oblongata. These cranial nerves control speaking and swallowing. Dysarthria develops. Dysphagia for solid and liquids develops after speech difficulties. Atrophy of the tongue and fasciculations thus affect tongue movement. Patients develop sialorrhea resulting in difficulty managing of their oral secretions and subsequent drooling. This symptom is due to swallowing difficulty and a possible mild upper motor neuron form of bilateral facial weakness which affects the lower part of the face (VII cranial nerve). The gag reflex is usually preserved. Respiratory problems develop. They include a spectrum from nocturnal hypoventilation, dyspnea, orthopnea, morning headache from hypoventilation, and sleep disturbance to respiratory failure. Other cranial nerves are preserved.

to a lower motor neuron lesion either at the nuclear or fascicular level in the medulla oblongata. These cranial nerves control speaking and swallowing. Dysarthria develops. Dysphagia for solid and liquids develops after speech difficulties. Atrophy of the tongue and fasciculations thus affect tongue movement. Patients develop sialorrhea resulting in difficulty managing of their oral secretions and subsequent drooling. This symptom is due to swallowing difficulty and a possible mild upper motor neuron form of bilateral facial weakness which affects the lower part of the face (VII cranial nerve). The gag reflex is usually preserved. Respiratory problems develop. They include a spectrum from nocturnal hypoventilation, dyspnea, orthopnea, morning headache from hypoventilation, and sleep disturbance to respiratory failure. Other cranial nerves are preserved.

Limb Symptoms

Multiple limb symptoms are noted including muscle weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, spasticity, and hypertonia. Focal muscle atrophy usually involves the muscles of the hands, forearms, shoulders, proximal thigh, or distal foot muscles. Fasciculations are noted in more than one muscle group. Spasticity is apparent in both upper and lower extremities. Deep tendon reflexes are hyperactive, and clonus is observed.

Cognitive and Behavioral/Emotional Symptoms

Recent recognition of cognitive impairment is included in the symptom cluster of some ALS. For those patients who do have cognitive impairment, the frontal lobe is involved. Possible deficits include attention, concentration, executive function, cognitive flexibility, word finding, and working memory.13, 14, 15 Symptoms may advance to dementia in some patients.

Patients with ALS may demonstrate pseudobulbar affect, emotional labile, anxiety, or depression. Pseudobulbar affect syndrome is characterized by involuntary crying or uncontrollable episodes of crying and/or laughing, or other emotional displays occurring secondary to neurologic disease.16 Patients may cry uncontrollably, unable to stop themselves for several minutes. Episodes may also include mood-incongruence in which a patient might laugh uncontrollably when angry or frustrated. Emotional lability or pseudobulbar affect as a result of loss of normal inhibition or laughter and crying may be associated with upper motor neuron degeneration.5 Cognitive impairment is noted in 25% to 50% of patients who undergo neuropsychological testing, and approximately 15% develop frontotemporal dementia.5 Depression and anxiety are common throughout the course of the illness. Anxiety may be related to respiratory insufficiency while depression may be related to the diagnosis, hopelessness of the future, and functional deficits. These problems need to be recognized and treated in the course of the illness.

Summary of Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of ALS can vary from patient to patient. A summary of the signs and symptoms include the following.13, 14, 15

Fatigue

Muscle weakness, wasting, and atrophy: the muscles most commonly affected are the intrinsic muscles of the hand, as evidenced by clumsiness. The next most commonly affected muscles are the shoulder and upper arm muscles. The lower limbs are affected last; they characteristically feel heavy and are subject to fatigue and easy cramping.

Muscle spasticity and hyperreflexia

Fasciculations

Brainstem signs occur. Atrophy of the tongue causing dysarthria and dysphagia occur. The muscles of speech, chewing, and swallowing are affected so that dysarthria and dysphagia occur. Sialorrhea is also noted.

Dyspnea that progresses to respiratory paralysis

Cognitive changes including pseudobulbar affect to frontotemporal dementia

Depression and anxiety

Course of Illness

Because the onset of ALS is insidious, the early signs and symptoms may be overlooked. Diverse muscle groups gradually become involved. The degree of weakness, atrophy, muscle wasting, and fasciculations increase over time. Fatigue and reduced exercise capacity are common symptoms in ALS and ultimately, most patients need assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs). As the disease progresses, the arms and legs become severely impaired, and spasticity and hyperreflexia are noted. If the frontal lobe is involved, emotional lability and cognitive impairment are seen. When the brainstem is involved, the muscles of speech and swallowing are affected. Speech is thick and hard to understand, and chewing, swallowing, and managing secretions become very difficult. Dysphagia develops in most patients with associated weight loss and malnutrition, both indicators of a poor prognosis. In the advanced stage, most patients develop respiratory compromise leading to dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, hyperventilation with resultant hypercapnia, and early morning headaches. Speaking may no longer be possible. Death usually occurs as a result of progressive weakening of the respiratory muscles aspiration, pneumonia, or respiratory failure.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ALS is made primarily based on the history and a neurological examination that demonstrates of progressive upper and lower motor neuron disease in an asymmetrical localization. Neurophysiological studies are helpful to support a suspected diagnosis; they help to demonstrate signs of lower motor dysfunction which include fibrillations, denervation, muscle wasting, and atrophy, and most importantly to exclude other disorders of the peripheral nerves. Studies ordered include nerve conduction studies and conventional electromyography. Neuroimaging studies may be ordered to rule out any treatable structural lesions that mimic ALS by producing symptoms of upper motor and lower motor neuron disease.4

Other tests and laboratory tests may be ordered. In ALS, the serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level is often elevated. Elevated serum creatinine is related to skeletal muscle mass loss. Genetic testing is important if familial ALS is suspected. Neuropsychological testing may be warranted either initially or during the course of the illness if cognitive impairment is suspected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access