A

ABUSE, SUSPECTED

Abuse may be suspected in any age-group, cultural setting, or environment. The patient may readily report being abused or may fear reporting the abuser. Types of suspected abuse include neglect and physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse.

In most states, a nurse is required by law to report signs of abuse in children, older adults, and the disabled. (See Common signs of neglect and abuse, page 2.) Use appropriate channels for your facility and report your suspicions to the appropriate administrator and agency. Document suspicions on the appropriate form for your facility or in your nurse’s notes. If the patient is a child, interview the child alone and try to interview caregivers separately to note inconsistencies with histories. An injunction can be obtained to separate the abuser and the abused, ensuring the patient’s safety until the circumstances can be investigated.

Remember, certain cultural practices that produce bruises or burns, such as coin rubbing in Vietnamese groups, may be mistaken for child maltreatment. Regardless of cultural practices, the judgment of child maltreatment is decided by the department of social services and the health care team. (See Tour role in reporting abuse, page 3.)

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

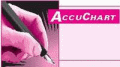

When documenting, record only the facts and be sure to leave out personal opinions and judgments. Record the time and date of the entry. Provide a comprehensive history, noting inconsistencies in histories, evasive answers, delays in treatment, medical attention sought at other hospitals, and the

person caring for the individual during the incident. Document your physical assessment findings using illustrations and photographs as necessary (per police department and social service guidelines). Describe the patient’s response to treatments given. Record the names and departments of people notified within the facility. Provide the names of people notified, such as social services, the police department, and welfare agencies. Record any visits by these agencies. Include any teaching or support given.

person caring for the individual during the incident. Document your physical assessment findings using illustrations and photographs as necessary (per police department and social service guidelines). Describe the patient’s response to treatments given. Record the names and departments of people notified within the facility. Provide the names of people notified, such as social services, the police department, and welfare agencies. Record any visits by these agencies. Include any teaching or support given.

COMMON SIGNS OF NEGLECT AND ABUSE

If your assessment reveals any of the following signs, consider neglect or abuse as a possible cause and document your findings. Be sure to notify the appropriate people and agencies.

NEGLECT

Failure to thrive in infants

Malnutrition

Dehydration

Poor personal hygiene

Inadequate clothing

Severe diaper rash

Injuries from falls

Failure of wounds to heal

Periodontal disease

Infestations, such as scabies, lice, or maggots in a wound

ABUSE

Recurrent injuries

Multiple injuries or fractures in various stages of healing

Unexplained bruises, abrasions, burns, bites, damaged or missing teeth, strap or rope marks

Head injuries or bald spots from pulling out hair

Bleeding from body orifices

Genital trauma

Sexually transmitted diseases in children

Pregnancy in young girls or women with physical or mental handicaps

Verbalized accounts of being beaten, slapped, kicked, or involved in sexual activities

Precocious sexual behaviors

Exposure to inappropriately harsh discipline

Exposure to verbal abuse and belittlement

Extreme fear or anxiety

ADDITIONAL SIGNS

Mistrust of others

Blunted or flat affect

Depression or mood changes

Social withdrawal

Lack of appropriate peer relationships

Sudden school difficulties, such as poor grades, truancy, or fighting with peers

Nonspecific headaches, stomachaches, or eating and sleeping problems

Clinging behavior directed toward health care providers

Aggressive speech or behavior toward adults

Abusive behavior toward younger children and pets

Runaway behavior

YOUR ROLE IN REPORTING ABUSE

YOUR ROLE IN REPORTING ABUSEAs a nurse, you play a crucial role in recognizing and reporting incidents of suspected abuse. While caring for patients, you may note evidence of apparent abuse.When you do, you must pass the information along to the appropriate authorities. In many states, failure to report actual or suspected abuse constitutes a crime.

If you’ve ever hesitated to file an abuse report because you fear repercussions, remember that the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act protects you against liability. If your report is bona fide (that is, if you file it in good faith), the law protects you from any suit filed by an alleged abuser.

|

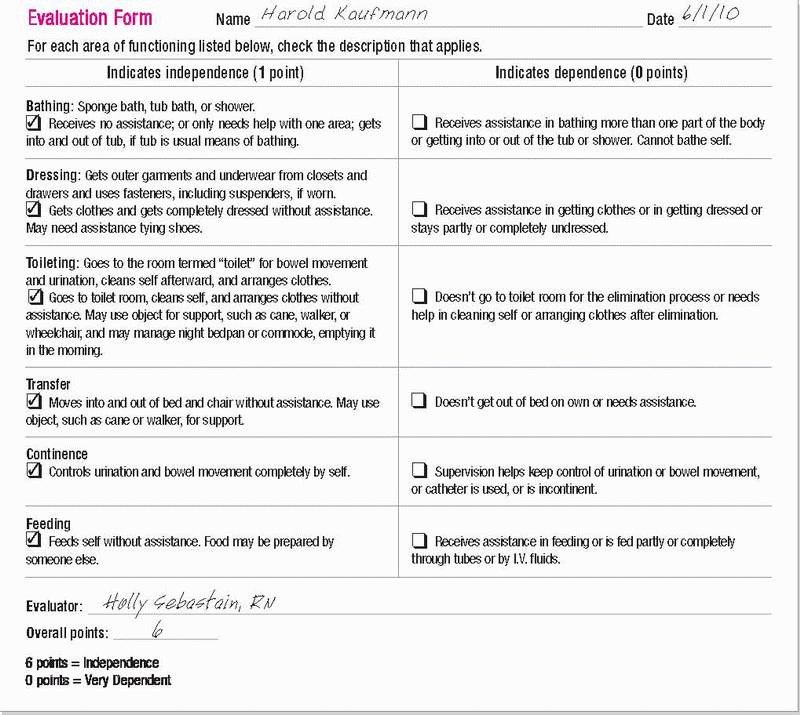

ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

Activities of daily living (ADLs) checklists are standard forms completed on each shift by the nursing staff and, in some cases, the patient performing the activities. After completion, you review and sign them. These forms tell the health care team members about the patient’s abilities, degree of independence, and special needs so they can determine the type of assistance each patient requires. Tools that are useful in assessing and documenting ADLs include the Katz index, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale, and Barthel index and scale.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Be sure to include the patient’s name, the date and time of the evaluation, and your name and credentials.

On the Katz index, rank your patient’s ability in six areas:

bathing

dressing

toileting

transferring

continence

feeding.

For each ADL, check whether your patient can perform the task independently, needs some help to perform the task, or can’t perform the task without significant help. (See Katz index.)

The Lawton scale evaluates your patient’s ability to perform complex personal care activities necessary for independent living, such as:

using the telephone

cooking or preparing meals

shopping

doing laundry

managing finances

handling medications

using transportation

doing housework.

Rate your patient’s ability to perform these activities using a threepoint scale: (1) completely unable to perform task, (2) needs some help, or (3) performs activity independently. (See Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale, page 6.)

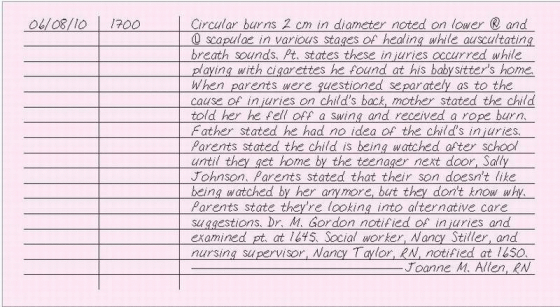

KATZ INDEX

KATZ INDEXBelow you’ll find a sample of the Katz index, which is used to assess six basic activities of daily living.

|

Adapted from Katz, S., et al.“Progress in the Development of the Index of ADL,” The Gerontologist 10(1):20-30, 1970. Copyright © The Gerontological Society of America. Reproduced (Adapted) by permission of the publisher.

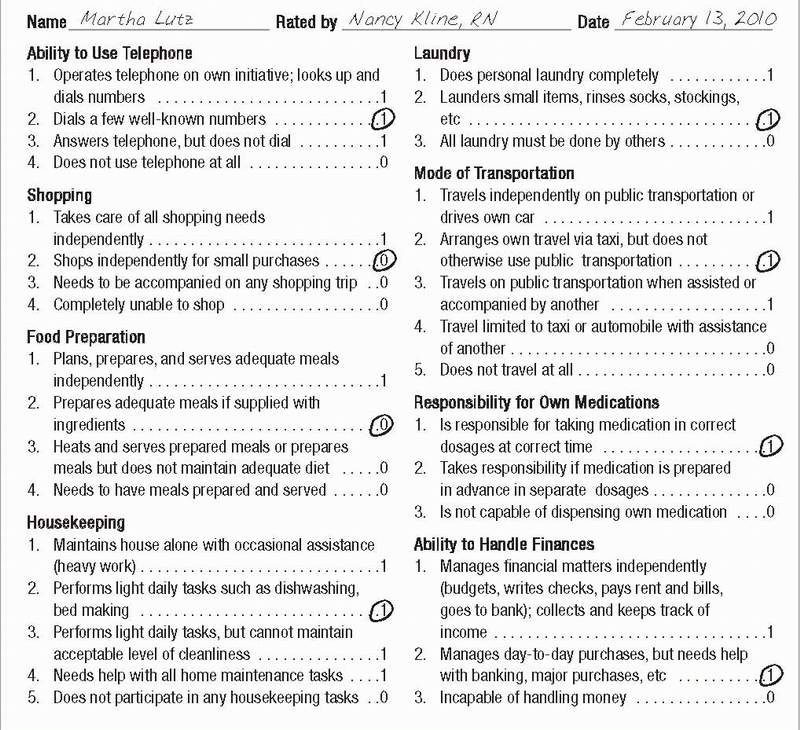

LAWTON INSTRUMENTAL ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING SCALE

LAWTON INSTRUMENTAL ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING SCALEThe Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale evaluates more sophisticated functions—known as instrumental activities of daily living—than the Katz Index. Patients or caregivers can complete the form in 10 to 15 minutes. For each category, circle the item description that most closely resembles the client’s highest functional level (either 0 or 1).

|

Lawton, M.P., and Brody, E.M.Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living,The Gerontologist 9(3):179-186, 1969. Copyright © The Gerontological Society of America. Reproduced (Adapted) by permission of the publisher.

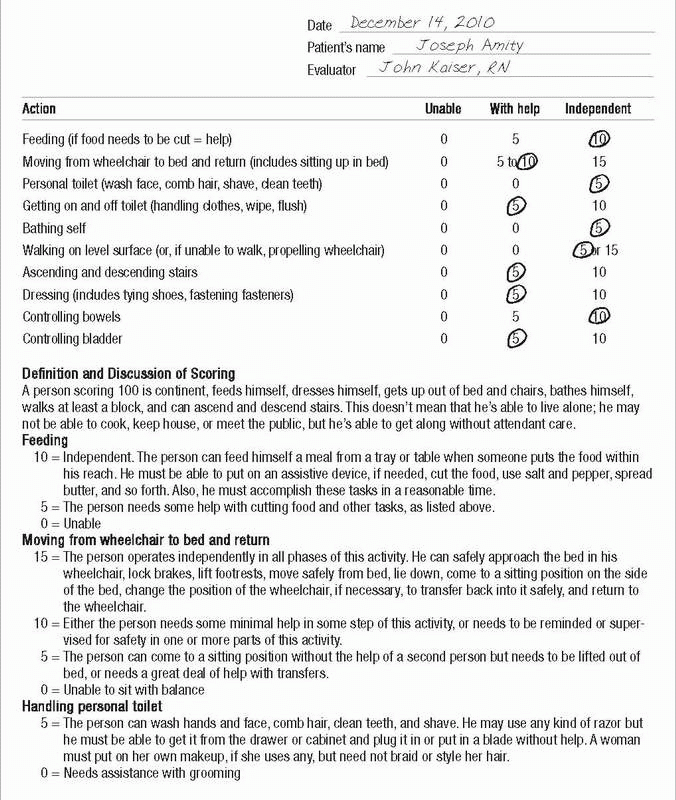

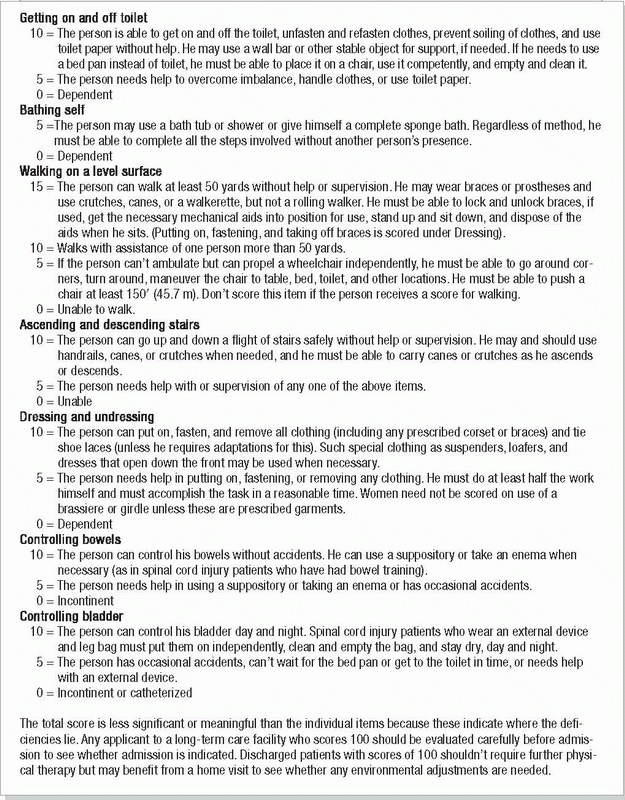

BARTHEL INDEX

BARTHEL INDEXThe Barthel index, shown below, is used to assess the patient’s ability to perform 10 activities of daily living, document findings for other health care team members, and reveal improvement or decline.

|

|

© Adapted with permission from Mahoney, F.I., and Barthel,D.W.“Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index,” Maryland State Medical Journal 14:62, 1965.

The Barthel index and scale is used to evaluate:

feeding

moving from wheelchair to bed and returning

performing personal hygiene

getting on and off the toilet

bathing

walking on a level surface or propelling a wheelchair

going up and down stairs

dressing and undressing

maintaining bowel continence

controlling the bladder.

ADVANCE DIRECTIVE

An advance directive is a legal document used as a guideline for medical care of a patient with an advanced disease or disability who is no longer able to indicate his own wishes. Advance directives also include living wills (which instruct the doctor regarding life-sustaining treatment) and durable powers of attorney for health care (which names another person to act on the patient’s behalf for medical decisions in the event that the patient can’t act for himself).

Because laws vary from state to state, be sure to find out how your state’s laws apply to your practice and to the medical record.

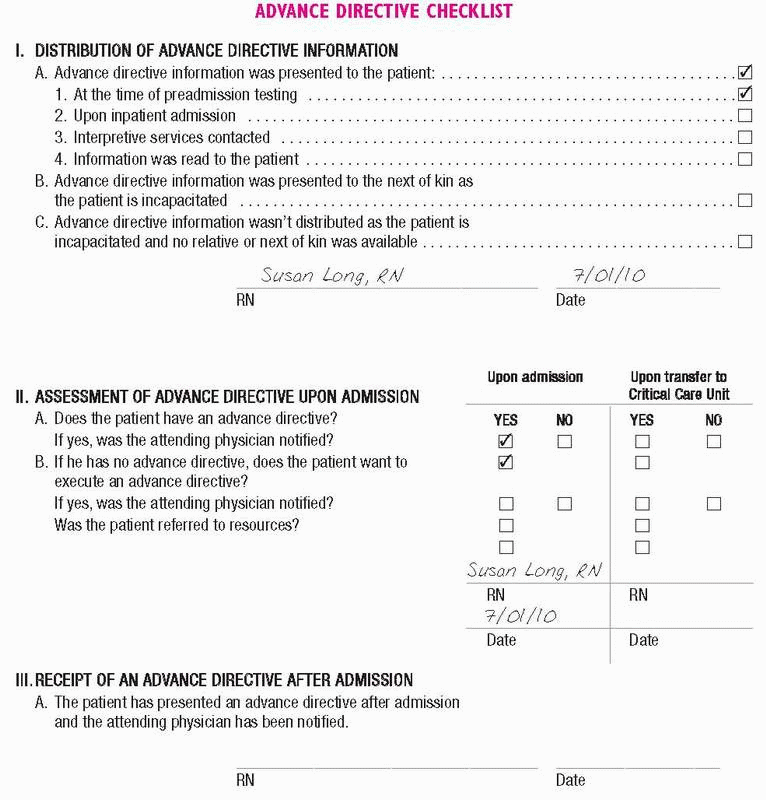

If a patient has previously executed an advance directive, request a copy for the chart and make sure the doctor is aware of it. Many health care facilities routinely make this request a part of admission procedures. (See Advance directive checklist, page 10.)

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

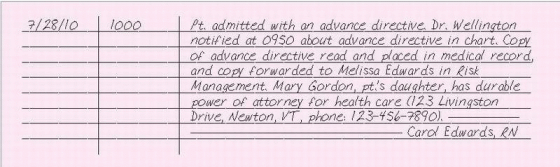

Document the presence of an advance directive, and notify the doctor. Include the name, address, and telephone number of the person entrusted with decision-making power. Indicate that you’ve read the advance directive and have placed a copy on the chart. If the patient’s wishes differ

from those of his family or doctor, make sure that the discrepancies are thoroughly documented in the chart.

from those of his family or doctor, make sure that the discrepancies are thoroughly documented in the chart.

If a patient doesn’t have an advance directive, document that he was given written information concerning his rights under state law to make decisions regarding his health care. If the patient refuses information on an advance directive, document this refusal using the patient’s own words, in quotes, if possible. Document any conversations with the patient regarding his decision making. Document that proof of competence was obtained (usually the responsibility of the medical, legal, social services, or risk management department).

|

ADVANCE DIRECTIVE, FAMILY CONTESTS PATIENT’S WISHES FOR

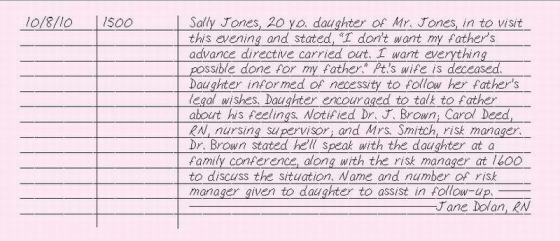

In most states, the advance directive is a legal document formulated by the patient while he’s of sound mind that dictates the patient’s wishes should he become incapacitated and unable to make decisions. Ideally, the patient should discuss his feelings and desires with his family members, and they should agree to the patient’s desires. However, there may be occasions when the family doesn’t agree with the advance directive or want it activated. Should this occur, the legality of the situation dictates that the living will is upheld. The family’s rights are superseded by the living will.

Should the family members express opposition to the advance directive, notify the patient’s attending physician, the nursing supervisor, and the risk manager. The family members can be encouraged to discuss their feelings with the patient and these individuals, or they may be referred for counseling that may help them in their situation.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document your conversation with the family members, recording their exact words in quotes. Record your assessment of the family situation. Document the name and department of any person notified. Chart the names of the notified doctor, nursing supervisor, and risk manager and the time they were contacted. Include any visits by these individuals and any counseling offered.

|

ADVANCE DIRECTIVE, NURSE WITNESS OF

Some patients wait until they’re hospitalized to consider an advance directive or to make significant legal decisions. If a patient wishes to execute a living will during his hospital stay, you aren’t required, or even permitted in some states, to sign as a witness. Check with your state’s laws about whether you can sign as a witness. In many facilities, the social services or risk management department oversees this process. Find out which is the responsible department in your facility. The person who acts as witness can be held accountable for the patient’s competence. Keep in mind that only a competent adult can execute a legally binding document. To prevent a patient’s relatives from later raising questions about his competence, the record should include documented proof of competence (usually the responsibility of the medical, legal, social services, or risk management department).

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document the patient’s desire to institute an advance directive. If social services and risk management are involved, document the time you notified them and the name of the person with whom you spoke. Record any visits from social services, risk management, or the patient’s own lawyer. Note that proof of competence was obtained, and record the name of the person who obtained it. If an advance directive is instituted, place a copy on the chart and notify the doctor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

ADVANCE DIRECTIVE CHECKLIST

ADVANCE DIRECTIVE CHECKLIST