D

DEATH OF A PATIENT

After a patient dies, care includes preparing him for family viewing, arranging transportation to the morgue or funeral home, and determining the disposition of the patient’s belongings. In addition, postmortem care entails comforting and supporting the patient’s family and friends and providing them with privacy.

Postmortem care usually begins after the patient’s death is certified. If the patient died violently or under suspicious circumstances, postmortem care may be postponed until the medical examiner completes an examination. Many states require that the area’s organ donation agency be notified of every death.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document the date and time of the patient’s death and the name of the doctor (or, in some states, the nurse) who pronounced the death. If resuscitation was attempted, indicate the time it started and ended, and refer to the code sheet in the patient’s medical record. Note whether the case is being referred to the medical examiner. Include all postmortem care given, noting whether medical equipment was removed or left in place. List all belongings and valuables and the name of the family member who accepted and signed the appropriate valuables or belongings list. Record any belongings left on the patient. If the patient has dentures, note whether they were left in the patient’s mouth or given to a family member. (If given to a family member, include the family member’s name.) Document the disposition of the patient’s body and the name, telephone number, and address

of the funeral home. Some facilities have a body release form that contains this information, along with information regarding contacting the medical examiner and organ donation agency. List the names of family members who were present at the time of death. If the family wasn’t present, note the name of the family member notified. Be sure to include any care, emotional support, and education given to the family.

of the funeral home. Some facilities have a body release form that contains this information, along with information regarding contacting the medical examiner and organ donation agency. List the names of family members who were present at the time of death. If the family wasn’t present, note the name of the family member notified. Be sure to include any care, emotional support, and education given to the family.

|

DEHYDRATION, ACUTE

Dehydration refers to the loss of water in the body with a shift in fluid and electrolytes, which can lead to hypovolemic shock, organ failure, and even death. Dehydration may be isotonic, hypertonic, or hypotonic. Common causes of dehydration are fever, diarrhea, and vomiting. Other causes include hemorrhage, excessive diaphoresis, burns, excessive wound or nasogastric drainage, and ketoacidosis. Prompt intervention is necessary to prevent complications, which can include death.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of your entry. Record the results of your physical assessment and any subjective findings. Include laboratory values and the results of any diagnostic tests (such as stool culture to identify the cause of excessive diarrhea). Closely monitor and record intake and output on an intake-output flow sheet. (See “Intake and output,” pages 216 to 218.) Record the name of the doctor notified, the time of notification,

and any orders given. Document your interventions, such as I.V. therapy, and the patient’s response. Record your actions to prevent complications, such as monitoring for I.V. infiltration and auscultating for breath sounds to detect fluid volume overload. Be sure to document patient education.

and any orders given. Document your interventions, such as I.V. therapy, and the patient’s response. Record your actions to prevent complications, such as monitoring for I.V. infiltration and auscultating for breath sounds to detect fluid volume overload. Be sure to document patient education.

|

DEMENTIA

Dementia, which is also referred to as senile dementia or chronic brain syndrome, is considered a syndrome rather than a distinctive disease process. It’s a progressive deterioration of intellectual performance characterized by memory loss, inability to perform abstract analysis, lack of judgment, and decline in language skills. Changes in personality and the inability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) progress slowly until they become obvious and devastating over time.

Nursing interventions are focused on helping the patient maintain an optimal level of cognitive performance, preventing physical injury, decreasing anxiety and agitation, increasing communication skills, and promoting the patient’s ability to perform ADLs.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Perform a neurologic assessment, as appropriate, including level of consciousness, appearance, behavior, speech, and cognitive function. If appropriate, record the patient’s exact responses. Document measures taken

to ensure patient safety, meet personal needs, and promote independence; also document the patient’s response.

to ensure patient safety, meet personal needs, and promote independence; also document the patient’s response.

|

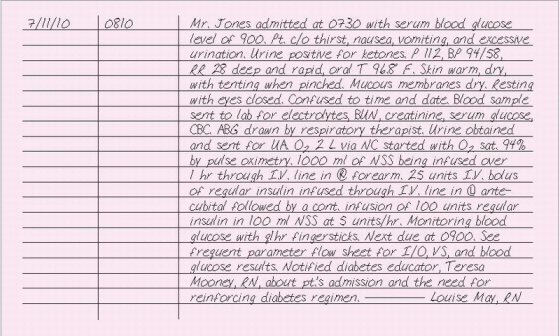

DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS

Characterized by severe hyperglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially life-threatening condition that occurs most commonly in people with type 1 diabetes (formerly known as insulin-dependent diabetes). An acute insulin deficiency precedes DKA, causing glucose to accumulate in the blood. At the same time, the liver responds to energy-starved cells by converting glycogen to glucose, further increasing blood glucose levels. Because the insulin-deprived cells can’t utilize glucose, they metabolize protein, which results in the loss of intracellular potassium and phosphorus and excessive liberation of amino acids. The liver converts these amino acids into urea and glucose. The result is grossly elevated blood glucose levels and osmotic diuresis, leading to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and dehydration. Moreover, the absolute insulin deficiency causes cells to convert fats to glycerol and fatty acids for energy. The fatty acids accumulate in the liver, where they’re converted to ketones. The ketones accumulate in blood and urine. Acidosis leads to more tissue breakdown, more ketosis and, eventually, shock, coma, and death.

When your assessment reveals signs and symptoms of DKA, you’ll need to act quickly to prevent a fatal outcome. Document your frequent assessments and interventions as they occur. Avoid charting in blocks of time. Although frequent notes take time, events will be fresh in your memory. Block charting looks vague, implies inattention to the patient, and makes it hard to determine when specific events occurred.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of your entry. Record your patient’s hourly blood glucose levels, intake and output, urine glucose levels, mental status, ketone levels, and vital signs, according to patient condition or unit policy. Depending on the facility, these parameters may be documented on a frequent assessment flow sheet. If using an electronic medication administration record, enter hourly blood glucose levels and treatment with insulin or titration of an insulin drip. Record the clinical manifestations of DKA assessed, such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, Kussmaul’s respira tions, fruity breath odor, changes in level of consciousness, poor skin tur gor, hypotension, hypothermia, and warm, dry skin and mucous mem branes. Document all interventions, such as fluid and electrolyte replacement and insulin therapy, and record the patient’s response. Record any proce dures, such as arterial blood gas analysis, blood samples sent to the labo ratory, cardiac monitoring, or insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter. Record results, the names of persons notified, and the time of notification. Include emotional support provided and patient education in your note.

|

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Before receiving a diagnosis, most patients undergo testing, which could be as simple as a blood test or as complicated as magnetic resonance imaging.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Begin documenting diagnostic testing by making notes about any preliminary assessments you make of a patient’s condition. For example, if your patient is pregnant or has certain allergies, record this information because it might affect the test or test result. If the patient’s age, illness, or disability requires special preparation for the test, enter this information in his chart as well.

Always prepare the patient for the specific test, and document any teaching you’ve done about the test and any follow-up care associated with it. Be sure to document the administration or withholding of drugs and preparations, special diets, food or fluid restrictions, enemas, and specimen collection.

|

DIETARY RESTRICTION NONADHERENCE

All mentally competent adults may legally refuse treatment, including following dietary restrictions. The patient or family may tell you about nonadherence, or you may suspect nonadherence based on test results, such as blood glucose levels or blood pressure readings. The patient may be nonadherent with diet for many reasons, including lack of motivation; lack of understanding; high cost of fresh fruits, vegetables, and specially prepared foods; lack of support; incompatibility with lifestyle, religion, or culture; lack of transportation to stores; unfamiliarity with new food preparation and cooking techniques; and diminished sense of taste.

Assess your patient to determine his reasons for not adhering with dietary restrictions. Help him develop a plan that will be compatible with his needs and cognitive ability. Explain the relationship between proper nutrition and health. Teach about the consequences of not complying with dietary restrictions. Refer the patient to the dietitian for consultation and teaching. He may need a social services consult if transportation or finances are a problem. The home care department may be able to arrange for a home delivery meal service, such as Meals On Wheels, if the patient can’t shop or prepare meals. Arrange for follow-up care and provide the patient with the names and telephone numbers of people to call with questions and concerns.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document nonadherence objectively. Use the patient’s own words, if appropriate, or describe the data that suggest nonadherence. Record the reasons for the nonadherence. Document your teaching about the diet, its relationship to the patient’s medical problem, and the consequences of nonadherence. Include the patient’s response to the teaching. Record the date and time of health care referrals made and the names of agencies and persons to whom the patient was referred.

|

DIFFICULT PATIENT

No doubt you’ve cared for dissatisfied patients and heard remarks like the following: “I’ve been ringing and ringing for a nurse. I could have died before you got here!” or “I’ve never seen such filth in my life. What kind of a hospital is this, anyway?” These are the sounds of unhappy patients. If you dismiss them, you may be increasing your risk of a lawsuit.

The first step in defusing a potentially troublesome situation is to recognize that it exists. Note the following signs of a difficult patient: constant grumpiness, endless complaints, no response to friendly remarks, and journaling of situations he views as wrong or causing him unnecessary distress. Use statements such as “You seem angry. Let’s talk about what’s bothering you.” After acknowledging the situation, continue to reach out to the patient, even if you don’t get a positive response. Never argue with the patient or try to convince him that a situation didn’t happen the way he thinks it did. Don’t make judgments, and don’t become defensive. Your patient needs reassurance that you’ll try your best to improve the situation.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document the patient’s complaints using his own words in quotes. Record the specific care given to your patient in direct response to complaints. If the patient threatens to file suit against you or the hospital, document this and notify your nursing supervisor or your facility’s risk management department. Record details of your contacts with the patient. Update your care plan to include more frequent contact with the patient.

|

DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS

Hospitals today commonly discharge patients earlier than they did in years past. As a result, the patient and his family must change dressings; assess wounds; deal with medical equipment, tube feedings, and I.V. lines; and perform other functions that a nurse traditionally performed.

To perform these functions properly, the patient and his home caregiver must receive adequate instruction. The nurse is usually responsible for these instructions. If a patient receives improper instructions and injury results, you could be held liable.

Many hospitals distribute printed instruction sheets that adequately describe treatments and home care procedures. The patient’s chart should indicate which materials were given and to whom. Generally, the patient or responsible person must sign that he received and understood the discharge instructions.

Courts typically consider these teaching materials evidence that instruction took place. However, to support testimony that instructions were given, the materials should be tailored to each patient’s specific

needs and refer to any verbal or written instructions that were provided. If caregivers practice procedures with the patient and family in the hospital, this should be documented, too, along with the results.

needs and refer to any verbal or written instructions that were provided. If caregivers practice procedures with the patient and family in the hospital, this should be documented, too, along with the results.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Many facilities combine discharge summaries and patient instructions in one form. This form contains sections for recording patient assessment, patient education, detailed special instructions, and the circumstances of discharge. (See The discharge summary form, page 100.)

When writing a narrative note about discharge instructions, include the following information:

date and time of discharge

family members or caregivers present for teaching

treatments, such as dressing changes, or use of medical equipment

signs and symptoms to report to the doctor

patient, family, or caregiver understanding of instructions or ability to give a return demonstration of procedures

whether a patient or caregiver requires further instruction

doctor’s name and telephone number

date, time, and location of any follow-up appointments or the need to call the doctor for a follow-up appointment

details of instructions given to the patient, including medications, activity, and diet (include any written instructions given to patient).

|

DO-NOT-RESUSCITATE ORDER

When a patient is terminally ill and death is expected, his doctor and family (and the patient if appropriate) may agree that a do-not-resuscitate (DNR), or no-code, order is appropriate. The doctor writes the order, and the staff carries it out if the patient goes into cardiac or respiratory arrest.

Because DNR orders are recognized legally, you’ll incur no liability if you don’t try to resuscitate a patient and that patient later dies. You may, however, incur liability if you initiate resuscitation on a patient who has a DNR order.

Every patient with a DNR order should have a written order on file. Some facilities have specific forms that help define what care the patient or family doesn’t wish delivered in the case of a code, such as no CPR or no intubation. The order should be consistent with the facility’s policy, which commonly requires that such orders be reviewed every 48 to 72 hours.

Increasingly, patients are deciding in advance of a crisis whether they want to be resuscitated. Health care facilities must provide written information to patients concerning their rights under state law to make decisions regarding their care, including the right to refuse medical treatment and the right to formulate an advance directive.

This information must be provided to all patients upon admission. You must also document that the patient received this information and whether he brought a written advance directive with him. (See “Advance directive,” page 9.) A photocopy of the directive should be placed in the patient’s record.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

If a terminally ill patient without a DNR order tells you that he doesn’t want to be resuscitated in a crisis, document his statement as well as his degree of awareness and orientation. Then contact the patient’s doctor and your nursing supervisor and ask for assistance from administration, legal services, or social services.

As a nurse, you have a responsibility to help the patient make an informed decision about continuing treatment. If the patient’s wishes differ from those of his family or doctor, make sure the discrepancies are thoroughly recorded in the chart. Then document that you notified your charge nurse, nursing supervisor or legal services.

|

DOCTOR’S ORDERS, CLARIFICATION OF

Although unit secretaries may transcribe orders, the nurse is ultimately responsible for the accuracy of the transcription. Only you have the authority and knowledge to question the validity of orders and to spot errors.

Follow your health care facility’s policy for clarifying orders that are vague, ambiguous, incomplete, or possibly erroneous. If you don’t have a policy to cover a particular situation, contact the prescribing doctor and always document your actions. Then ask your nurse administrator for a step-by-step policy to follow so you’ll know what to do if the situation ever recurs.

An order may be correct when issued but inappropriate later because of changes in the patient’s status. When this occurs, delay treatment until you’ve contacted the doctor and clarified the situation. Follow your facility’s policy for clarifying an order.

Document your efforts to clarify the order, and document whether the order was carried out.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Write an order clarification on the doctor’s order sheet. Be sure to qualify the order by writing “order clarification” followed by the new complete order. If you refuse to carry out an order you believe to be written in error, record your refusal, your reasons for refusing, the names of the doctor and charge nurse or nursing supervisor you notified, the time of notification, and their responses.

|

DOCTOR’S ORDERS, FAXING

The doctor may use a facsimile, or fax, machine to transmit patient orders. Faxing has two main advantages: It speeds transmittal of the doctor’s orders, and it reduces the likelihood of errors. When you receive a doctor’s order by fax, place the fax in the patient’s medical record, and

transcribe the order onto the doctor’s order sheet if your facility requires this. The order is then carried out like any other order.

transcribe the order onto the doctor’s order sheet if your facility requires this. The order is then carried out like any other order.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the faxed order on the doctor’s order sheet as soon as possible. Note the date and time, and then copy the order as written on the fax. On the next line, write “faxed order.” Then write the doctor’s name, and sign your name. Draw lines through blank spaces in the order.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

THE DISCHARGE SUMMARY FORM

THE DISCHARGE SUMMARY FORM